There’s a point in high school when you realize you are different. It could be as simple as enjoying different music, hobbies or having different interests as your friends. You might enjoy anime from time to time or sing in an a cappella group or *gasp* even enjoy math. You could like people of the same gender as yourself, hate your parents or have a shrine to Zac Efron in your room. For me, it was my health.

Instead of worrying about my homecoming dress or ACT scores like my fellow high schoolers, I was learning words such as “hypertension” and “tachycardia,” because these symptoms plagued my daily life. And no, unfortunately the new additions to my vocabulary did not help me on the SATs. You win some, you lose some.

After months of confusion and misdiagnosis, at the age of fifteen I was diagnosed with a form of dysautonomia called Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome. (I promise it gets easier to read and say, but let’s abbreviate it ‘POTS’ for short.) POTS is characterized by an abnormal heart rate upon standing and an immediate drop in blood pressure for patients. Many diagnosed often experience nausea, fatigue and heart palpitations along with a plethora of other symptoms.

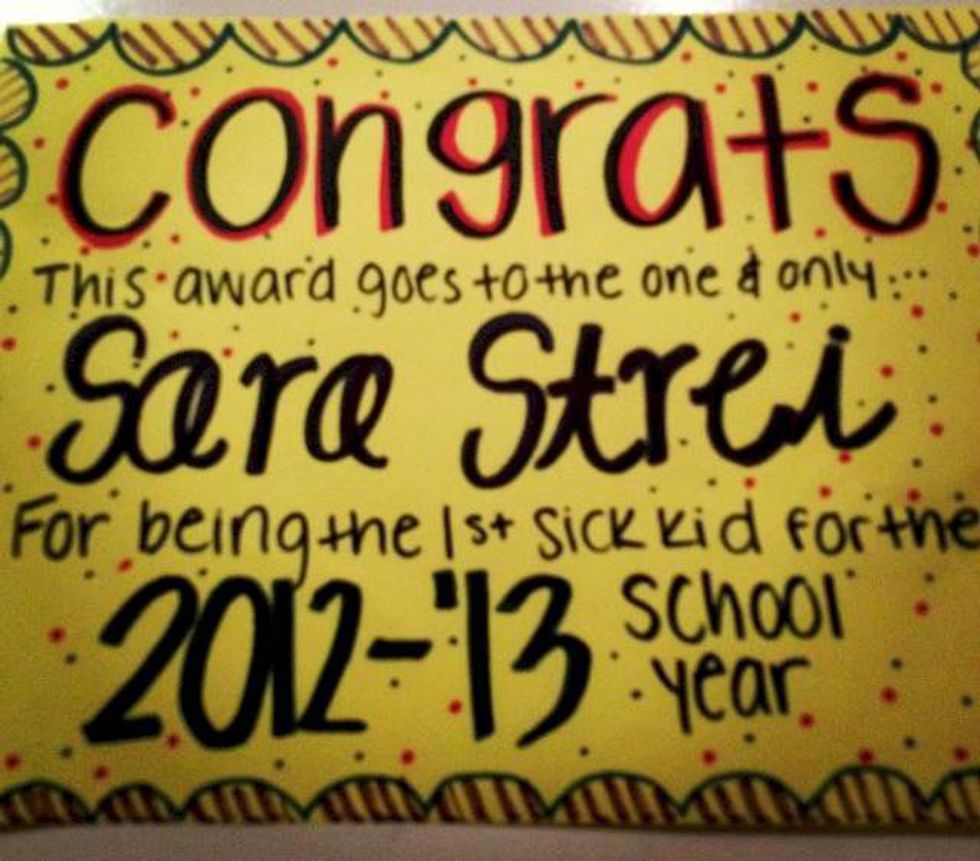

My first day of junior year started out with me vomiting my guts out in the nurse’s office before first period. Before. First. Period. After convincing myself I was the weakest link and even winning the “first sick kid of the year award” I sent myself home in hopes of watching "The Lizzie McGuire Movie" and eating ramen thinking it was a stomach bug.

Unfortunately, I would not attend school again until my symptoms were in control, so I ended up being home-schooled for six months by a dude from Nepal named Subash. We got pretty tight even though I didn’t learn much, and I watched all of "One Tree Hill" in three weeks.

Although home school had its perks, I missed out on being a “normal” teenager and attending pep rallies, sleepovers and eating whatever I wanted. All of this was changed by my illness.

I felt defined by it. Although POTS is an “invisible illness,” and there are no symptoms you can see, I felt like I had a sign on my forehead that I wasn’t the same as my peers. That for some reason, my body was different, and it felt like it was destroying me from the inside out. Being attacked by your own body is a terrifying reality that so many have to face.

When I was first diagnosed, I was angry. Livid in fact. Why did my genes cause this? Why couldn’t doctors make me feel better instantly? Why does no one understand how I feel? But I don't want them to pity me. There's no way anyone could understand.

But eventually, those feelings changed over time. Thanks to my doctors who worked tirelessly to make sure I was as comfortable as I could be and distracting me when they put in my IVs. Thanks to my home school teacher who understood that Tuesdays at 8 p.m. were for "Pretty Little Liars" and not chemistry. Thanks to my friends for making me laugh and standing by my side. Thanks to my parents who dedicated each and every day to making me feel loved.

And thanks to strangers. When you hold a door open for someone or send a smile their way, you have no idea the impact you can have on a person’s day. A small act of kindness goes a long way, even when you don’t realize it.

Right now there are 7.3 billion people in the world (thanks Google)! Every single person is going through something you don’t know about. My illness taught me to try and do something every day for someone else. Like letting someone merge before you on the highway, sending an email to your grandma or donating to a charity that’s important to you. Now that’s a way to leave a positive impact on the world.

Have you ever seen a stranger’s face when you’ve bought their Starbucks for them? And have you ever seen mine when you see it’s a venti Frappuccino? Like I said before, you win some, you lose some.