My mom often describes five-year-old me as "a preschooler with a potbelly, a New York accent, and the voice of a trucker." I was a handful. I'd march around kicking boys in the shins, defying my babysitters, and locking my little sister in the bathroom (in fairness, I taught her how to unlock the door first, but she was three at the time so my training didn't really stick). I was one of those kids who made adults mutter, "here comes trouble," and "what are you up to?" when I walked into a room. And my voice played a large part in that. It was deep. Like Disney-villain-revealing-her-evil-plan deep.

Don't let the top-knot or the tutu fool you. That is the face of a child who's been scheming since six that morning. As you can imagine, my voice didn't get any higher with age. When I started singing in my middle school choir, I was a definitive alto. In my high school's vocal jazz group, my fellow second altos and I proudly sang the lowest notes possible, smirking when the sopranos bottomed out. I had a deep voice. I didn't sound light and airy like Ariel or Sleeping Beauty. I sounded tough and menacing, like Ursula or Maleficent. And I was cool with it. That was just how I sounded.

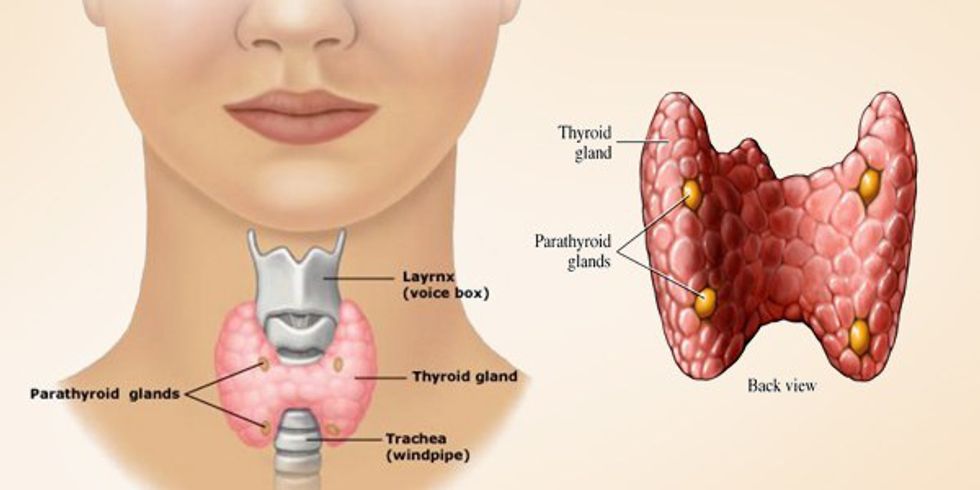

The summer before my senior year of high school, everything changed. A few months earlier, my sister pointed out a lump at the base of my neck. It was small, maybe three centimeters, and barely visible unless you were really looking for it. But if you placed two fingers on the little hollow where my collar bones meet my sternum, you could feel it. When my mom took me to our family doctor to get checked out, we were prepared for her to brush it off as a swollen lymph node, shaking her head at how paranoid parents were these days. But from the moment she put her fingers on that little hollow, she looked concerned. She told us that the lump was probably attached to my thyroid, but refrained from telling us anything else. "I don't want to give you any misinformation," she said. Wide-eyed, my mom and I left her office with a referral to see an ENT.

Two months, an aspirated biopsy, and several doctor's appointments later, surgery was the only way to find out if the tumor on my thyroid was benevolent or malignant. My doctor didn't want to take out my whole thyroid if he didn't have to, so he decided to run tests on the tumor in surgery. The plan was pretty simple. If it came back negative for cancer, he'd only take out half. If not, he'd take out the whole thing.

I woke up after the surgery with tears running down my face, turning to my parents to ask them what happened. I opened my mouth, but all that came out was a wheeze. My parents exchanged a worried look. I took a slow, deep breath in, wincing as every muscle in my neck struggled to open my airway wider. "Half or whole?" I croaked, silently panicking over how difficult it was for me to communicate. My parents explained that while my doctor only took out half of my thyroid, it wasn't because he was able to rule out cancer. He just couldn't make sense of what he found and wanted to be sure before taking out too much.

A week later, we returned to the doctor's office, and he finally gave a name to the monster I'd been afraid of for months: a follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Those were just a bunch of big words that all meant the same thing to me: I had cancer. It was the "good cancer," which meant that after a little radiation, I would be fine. My biggest concern was healing, which turned out to be a longer process than any of us anticipated. Vocal cords are sensitive, high maintenance little divas, and even the slightest exposure to air can disturb them. Because the thyroid and the vocal cords live in the same little neighborhood in the neck, there was no way around irritating my vocal cords in surgery. My doctor had warned me that my voice would be hoarse for a while afterwards. I just didn't realize what that actually meant.

My voice was back to normal about a month after the first surgery. Unfortunately, that was right around the same time I had to go back in for a second surgery to take the rest of my thyroid out. The recovery from the first surgery was fairly quick and painless. It was the second surgery that really wrecked my voice. The expected recovery time was six to eight months, and my body decided to take its sweet time. I spent the majority of my senior year speaking with a voice that sounded somewhere between a broken accordion and an anti-smoking commercial. To make matters worse, my breathing was also affected. In one of the surgeries, my pharyngeal nerve was damaged, causing my vocal cords to open only halfway when I took a breath in. Because the airway was so small, I often wheezed instead of breathing, and it only took a couple stairs or a few seconds of speed walking for me to lose my breath. It was impossible to pretend that nothing had happened to me.

When my voice finally came back eight months later, it was higher. My doctor had informed me that there was a chance it would be different after my vocal cords healed, but I still kept waiting for my voice to drop, like a prepubescent boy on the eve of his thirteenth birthday. But it never dropped. It grew stronger, cracking and wavering a little less each day. Eventually I was even able to sing a little bit, but my already limited range had shrunk even smaller. It was my breathing that never quite healed. The damage my doctor thought was temporary turned out to be permanent, and to this day I hum and wheeze more than I'd like to admit. My voice had changed for good.

People used to tell me that I should write about it. Senior year of high school is a weird time without a life-changing illness thrown into the mix, so I definitely have my fair share of stories to tell. But for a long time, I didn't know how to talk about what was happening. On one hand, it felt like I was always talking about it: updating family and friends after every checkup, assuring my loved ones that I was tired but fine, explaining my situation to an unsuspecting Starbucks barista who heard my voice and asked if I was sick. But on the other hand, it felt like I was never saying anything real. I didn't know how to. My voice -- literally and figuratively -- was different.

Before cancer, I sang in three school choirs, played varsity soccer, and served in my school's missions program. After the surgeries, my voice was too weak to sing in choir, my breathing made it impossible to continue playing soccer, and any message of hope I was supposed to share with others felt disingenuous. I used to be busy, running from class to practice to rehearsal to meetings, and then doing it all over again the next day. Suddenly, I had all this free time I didn't know what to do with. The way I understood the world was different. The way I interacted with it was different. I felt lost and confused and really, really angry. And I didn't know what to say about it.

So here I am, writing this article. I'd love to tell you that now, three and a half years later, I've fully dealt with the ways my life has changed. In some ways, I have. But like most things in life, it's a process, and I'm constantly reconstructing and relearning what it means to be me. I can tell you that about a year and a half ago, I was declared officially cancer free. And as grateful as I am to my brilliant doctor, I only see him once a year for an annual check up, and we mostly just talk about my life. Three and a half years ago, I lost my voice. I lost sight of who I was and how to function. We all have stories, and this is only part of mine. Three and a half years ago, I lost my voice. Now I'm finally working on taking it back.