I met him in eighth grade. I was on the way home from soccer with a nagging pain in the corner of my jaw. My mom kept asking me questions--something about my head or ]\my neck but I wasn’t really listening. The mountains curved outside my window. I watched until they made me feel sick. My mom had stopped talking. Soft music was playing from the car’s speakers. It felt like an eternity before we got home, mostly because the clock was too blurry for me to see.

He wrapped his arm around me when we got to the house. My mom unlocked the door; I stepped out onto the driveway, and fell into his arms. His hands scratched against the skin of my half-covered arm. He spoke to me in hushed tones as we walked, first up the steps and then through the door to the kitchen. This is it, he told me. My mom was next to me, nearly screaming in my ear. I could not hear her but I could hear him. He left early that night because I was tired and my parents were worried.

I was diagnosed with a concussion within the next week. We took a few trips to the concussion doctor. She asked why my hands were sweaty and I told her I hated doctors. I stayed home for a week with my dad who stayed in his office in the basement. I tried and failed to get a tan outside. He held my hand through it all, creating human-shaped imprints in the grass next to my towel. He asked me questions that I was unable to answer. Will you always be so bored? Why don’t you have anyone to talk to?

I hope not, I told him. I don’t know why, I whined. Stop whining, he told me. You sound like a baby. He stood and caught my eyes for a moment, shooting me a brief look of disgust. Wait! I screamed as he slinked away, reaching my tired arms into the warm May air, fingers twitching, palms sweating. He didn’t look back.

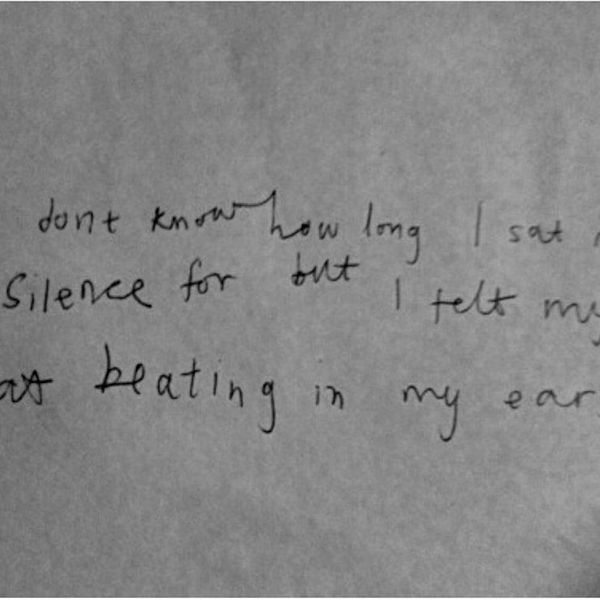

And then I was alone--no phone to use, no computer to type on, no TV to watch--only my beat-up IPod and its collection of pirated music. I leaned back, laid my head on the grass, desperately fighting the feeling of ants crawling through my hair, and pushed two ear buds into my ears. Music was already playing, almost too quiet for me to hear. It took a few minutes for me to realize what was playing: “Somebody That I Used to Know.” The same song that the girls on my soccer team used to sing during car rides to practice while I slumped by the window, running over the details of the last game in my head.

A month later, I was at a tournament in New Jersey with my dad. We had just gone to see Princeton so I felt innocently optimistic. We had a half hour until warm-ups so I begged my dad for money for the Italian ice truck parked by the edge of the field. He agreed and I only ate half of it, the multi colored sludge running down my chin and onto my uniform. My dad told me it was time to go so I threw my half-finished cup of ice into the trash can as I ran towards the rest of my team. He was not with me. We had grown apart since I had started playing again. I just didn’t have time for him anymore.

The game started; we were playing a team that we didn’t think we could beat. I was at left defense; there was a girl running at me; I was in front of her; she was in front of me; I had the ball; my ankle was crushed.

My coach carried me off so that I could ride in the golf cart. I sat on the table in the trainer’s tent and talked to them about their jobs. My dad drove to Walgreens to get crutches. I looked down for a while, considering whether the ice on my skin was more painful than my actual injury, and barely caught him walking over. I caught his eye as he weaved through the pairs of mothers and daughters and the crowds of boys with bulging backpacks. He looked so out of place there, but I could not turn him away.

What did you do this time? he asked me. Something bad, I told him, voice shaking, ankle finally gone numb. Looks like we should start seeing each other again, he stated, almost smiling. I tried to smile back, but my lip just quivered.

We spent more time together that summer. He sat with me at soccer camp where I had to watch because I was unable to play. He held my hand while I called my parents, begging them to take me home. He told me I was weak. He told me I would never play well again. I told him that I hoped he wasn’t right. He came with me to my friends’ houses and to horseback riding camp. He biked next to me at physical therapy, repeating a few key phrases. You are so out of shape, he told me. You look ridiculous and unathletic, he sneered. I looked out the window at the always-packed parking lot and tried to tune him out. He came on vacation with us that year. It was tough to fit him into the already-tight RV, but he insisted so I made room. We spent a lot of time together. He kept me up late at night talking. He didn’t like my bathing suit or the way my mom snored. I was anxious and sleep-deprived; I started to agree with him.

We grew apart again when I entered high school. I didn’t start seeing him regularly again until a few weeks before my birthday. He watched while I twisted my knee and covered his smile with his hand as I limped off the field, into the car, and into the doctor’s office where the overeager resident told me, while bending my knee in the wrong direction, that I had definitely torn my MCL. She scheduled me for the soonest MRI and he told me that I was no longer free for the rest of the week.

I tried to stay positive. The doctors told me that my injury was serious, that it would be a year before I could play sports again. He sat beside me, nodding and tapping his foot. My mom cried—that was the end of my hope for a soccer scholarship. I watched her and wondered if I felt something similar. He went with me to physical therapy at first and stopped coming when he saw that I was actually having fun. I spent lots of time with him that summer, though. I didn’t go horseback riding because it was too dangerous. He sat with me on the couch while I watched Greys Anatomy for hours and hours. Why aren’t you doing something? he asked me. I can’t believe you think you’ll ever be good at sports again.

He was laughing, always laughing, while I tried to run for the first time, laughing to the point of tears while I gasped for breath on the side of the track. You are a failure, he told me. You aren’t an athlete anymore. I lost my positive attitude. I lost my ambition. I had to force myself to run on the treadmill when snow started to cover the track. I stopped going to physical therapy as I neared the one-year mark. I told my mom that my knee hurt, that my muscles weren’t strong enough, that I didn’t feel mentally ready in an effort to push back the date. But it came eventually. I told my mom that I wanted to focus on lacrosse at first. I skipped soccer practice. He patted me on the back and told me it would be a miracle if I made the team.

I was in my car a few months ago, and I was scanning through stations. Just when it seemed like every worthwhile station was playing commercials, I heard a familiar tune. It took me a few seconds, but I eventually recognized it: “Somebody That I Used to Know” in all its 2012 indie glory. I listened without listening to the lyrics, concentrating on the road, and felt that bittersweet nostalgia that is more common among post-college adults. I tried to smile, but he pushed his finger into my lips. I was right, he told me. I nodded, stupid tears pooling in my eyes, but I did not let them fall. That was it, he told me. That was the beginning of you and me.