When I was 7 years old, after watching the movie "Maid in Manhattan," I told my father that one day I would go to Manhattan and make my dreams come true, just like Jennifer Lopez. New York was not a mega metropolitan city, with a population of 8.4 million people who always seem to be walking toward a place they never get to. New York was my Wonderland, my Chocolate Factory, my Narnia. A place where magic existed. My father looked at me, smiled and told me I was crazy. But now, thirteen years later, as I stand by the balcony and look up at the moon, 40 Wall Street and the Empire State building both compete for my attention. I text my father: "Dad, I am in Manhattan." I almost add, "It must have been the craziness."

The first person I meet in New York is Muhamid, a taxi driver. Before I start speaking to Muhamid, I notice the Moroccan flag on his worn out dashboard, next to a picture of a child diving into a big swimming pool. “Are you from Morocco?” I urgently ask him. “Yes, I am,” he proclaims. “Casablanca or Marrakesh?” I ask “Casablanca!” He exclaims, noticing my knowledge of what used to be his home. “Have you been?” I explain to him about my very close friend, Sarah, from Marrakesh who I am meeting at the hotel he is taking me to. I also tell him that I come from Zimbabwe. I do this in my broken French, but Muhamid kindly pretends not to notice my grammatical mistakes. As he drives, Muhamid tells me how he found himself in America at the age of 27. After completing his degree in physics at the University of Hassan II, he could not find a job for three years. He came to America on a tourist visa and never left. “New York city is the most beautiful city ever! Once I arrived I knew I would not be leaving!” He shouts with a mouth that I can tell sees more cigarettes than coffee in a day. “I hoped to become Engineer, but they told me I had to go back and start again. So I just said non and I started working anywhere I could.” He says engineer with a French twang just like Sarah does when she speaks about her brother’s profession. He also does not say a solid no, he says non. His accent, for the first time since arriving in America, makes me feel welcome.

The child in the picture, I come to learn, is called Mustafa. He is Muhamid’s first-born son who has never been to Morocco but speaks fluent Arabic and French although he prefers speaking in English, unlike his father. Muhamid tells me, “Mustafa is a nationally ranked swimmer and has the fastest breast stroke time of all the children in his year.” Without waiting for my response, he continues to speak. “Before coming to America I was a football player, you know our football not this one here.” I smile and nod; I do know. I remember the days my brothers and I would play football with two concrete bricks as the goal posts and newspapers wrapped in plastic as the ball. “I wanted to be a professional player but you can’t do that in Morocco.” He stops at the red light and lights a cigarette. “Or in Zimbabwe either,” I add.

We look at each other, and without saying anything, we understand exactly why a child in our countries can never dream of becoming the next Lionel Messi. “Good thing Mustafa is here. He can become anything here,” I tell him and myself. “Mustafa is a good swimmer, he could never have had the opportunity to swim nationally in Casa.” He then pulls out a sheet of paper from the glove compartment and hands it to me, saying, “See, there is the time he did when this picture was taken.” I look at the paper, read the highlighted name, Mustafa Abdullah, and my whole body smiles. As we arrive at the hotel, Muhamid turns to me and asks, “And what about you? What brings you to the big jungle?” I laugh and say, “School. I am a freshman at Wesleyan University.” Muhamid’s face lights up when I mention "university," and he says to me, “I was too old to go back to school when I came here but I know you will do well. I know it!” I laugh and thank him. I step out of the taxi and walk into the hotel.

Now, as I stand on the balcony of the penthouse suite somewhere on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, I watch Sarah smile as I recount my taxi encounter and realize how much Muhamid reminded me of her, of genuine friendship, of shared dreams, and shared struggles. I reach out for her hand and ask, “Doesn’t New York at night look like Atlantis in a snowball with a lot of lights?” Sarah replies, “Yes, it does. It looks like a city where dreams can come true.”

“Doesn’t New York at night look like Atlantis in a snowball with a lot of lights?”

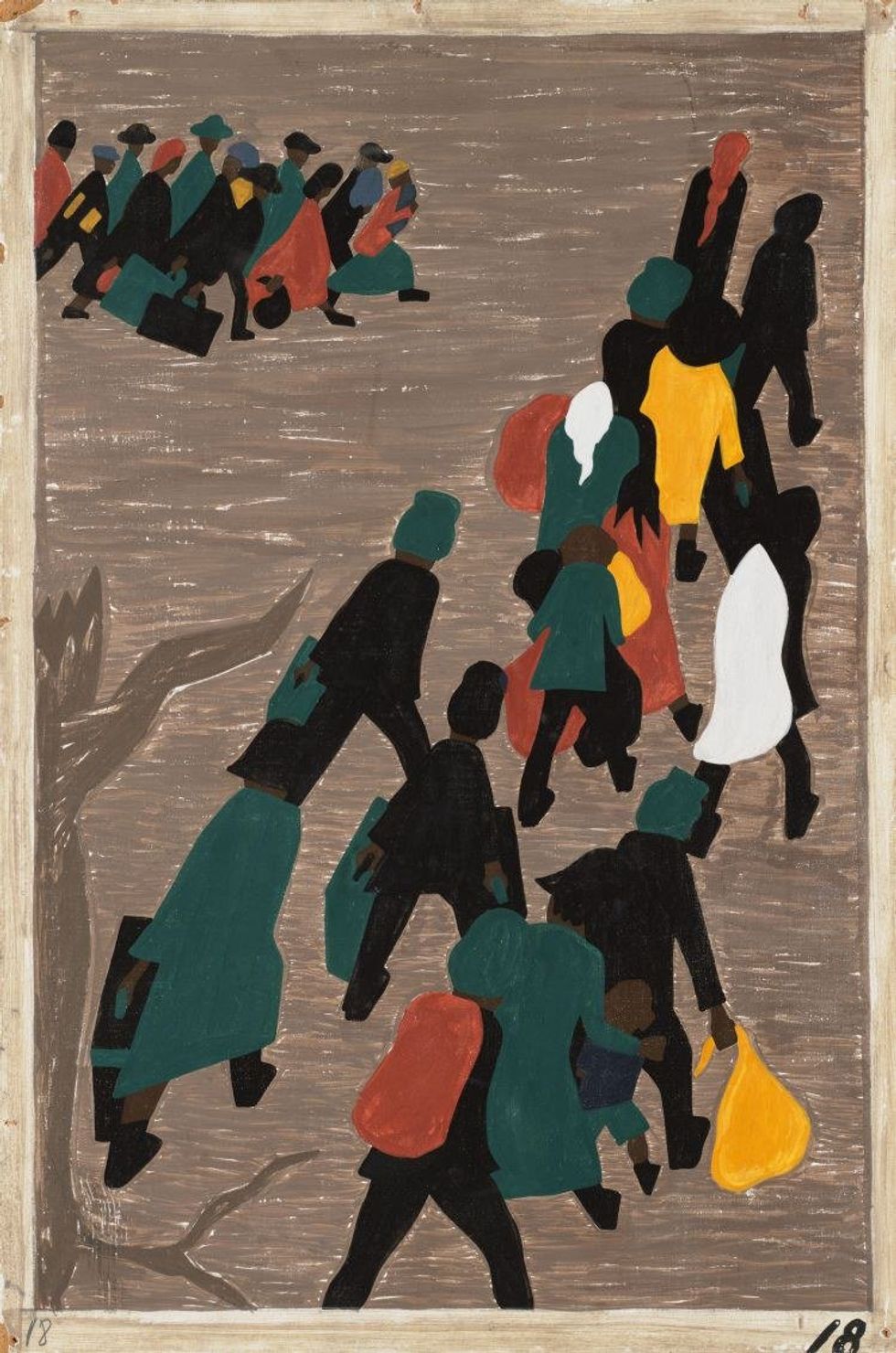

So when I heard an African American say, “African immigrants and Africans in the diaspora come and cut the line,” I thought of Muhamid. I thought of my mother’s friend who went from being a well-respected doctor in Zimbabwe to being a garbage collector in the United Kingdom. I thought of all these people and wondered just how exactly were they cutting the line? I thought of all my friends and myself, dispersed across college campuses all over the United Sates. I thought about our stories, full of insecurities, unmet expectations, struggles, tears, disappointments and hard work, and I wondered just how we were cutting the line? Were we cutting the line -- of the so-called American Dream -- by struggling to make our dreams come true despite all the shortcomings we had faced and still face? Perhaps.

To assume that all Africans who come to America or the United Kingdom come and become successful is canard. To assume that all Africans who come to America or the United Kingdom and are successful, do so because they took an opportunity intended for another Black Euro-American is callous. I cannot speak for the entire diaspora community but for those I do know, I can attest that for each success, achievement, or milestone obtained there has been a trade-off -- a price to pay. Being able to get a job in a country that is not yours, or in a country where you are constantly reminded of your difference even by those who you expect to sympathize with you, is beyond difficult. Thriving in a society where the color of your skin detracts from your merit is not easy. I do acknowledge that in America, African Americans have suffered and continue to do so, due to a pandemic issue of institutionalized racism. And although the African diaspora may not suffer from the generational consequences of institutionalized racism and oppression; the moment we arrive we are also subjected to it.

"It is this system that has created a “line” where there should be none."

Hence, instead of breeding and condoning sentiments such as “Africans in the diaspora are cutting the line,” the African American, Afro-Carribian, and African Diaspora community must realize that we are all bound together. We are bound by our history and by our present situation of exploitation and discrimination. I do understand that our experience of blackness is very different and complicated. My intention is not to bundle every single person who is considered black in the Euro-American context into one, my intention is for us to realize that while we are different and have nuanced narratives, we are all at the mercy of a singular oppressive system. It is this system that is truly the enemy. It is this system that has created a “line” where there should be none. Finally, if we are to realize this, then perhaps we will not become blind to one another’s struggles of existing within a black body.