My junior year of high school, as I was studying for a pre-calculus test, I felt the onset of terrible stomachache. I ran through what I had eaten and how much I drank throughout the day, but nothing clicked. I continued studying through the pain for hours, trying to ignore the feeling of my stomach twisting itself into a knot, so that I could be prepared for the next day. The pain became so excruciating that I finally hobbled into the kitchen to tell my mom how I felt. As soon as I found her and the words came out my mouth, I saw spots and fainted. I was neither dehydrated nor hungry, but I was overwhelmed by the amount of homework I had piling before me. I had had my first heavy panic attack.

I was always described as a Type A, organized person. I took my grades very seriously, my room was spotless, and I had a great sense of personal hygiene. But underneath this seemingly perfect façade, there remained a hectic side of myself that I hardly recognized and probably only my mother got a small glimpse of. I could accomplish this perfection only because it was part of a routine I couldn’t break. Even as a kindergartner, I would tell my friends I couldn’t come over because I had to clean every inch of my bedroom -- floor molding and all -- twice. My mom would find me at 3 A.M., working on a simple assignment that my classmates had finished in class, but I had rewritten several times because my handwriting was not to my standards. Just to get to bed in the evening, no matter how late, there was a 90-minute process of cleaning myself and preparing my bed that had to be accomplished before I could even consider closing my eyes. I would check that my alarm clock was set exactly three times. If I lost count, I had to start over. This could take 30 minutes.

Stress was nothing new for me by the time I started experiencing panic attacks in high school, but I hadn’t realized it. I knew I was more high strung than my classmates, but I also thought it was normal to wake up in the middle of the night, heart racing and terrified, because I forgot to staple an assignment.

The beginning of my panic attacks was a wake up call. They became more frequent as AP exams and college applications approached, and varied in their effects. Most of the time I hyperventilated, sometimes I started blacking out. Occasionally I would become so stressed that my fingers and toes would go numb, or I would overheat and have hot flashes, the way a laptop working overtime does. Twice I threw up. I could never control it, and I was always scared. More often then not, I found that, though I usually am a talkative and outgoing person, if I was feeling any level of stress, I could not speak or make eye contact with anyone. My mom would come into my room to check on me, and all I could do was blink and pinch myself because it was so painful to interact when I was feeling so overwhelmed.

The chronic stress that I had not realized I experienced on an everyday basis was now putting my body into distress. I felt sick to my stomach daily, but would also get colds and sinus infections often. After a few months of this, I finally started a discussion with my parents.

First it started with, “Why?” and I couldn’t explain it. I definitely had a demanding schedule and a heavy load of honors and AP classes that would leave me drowning in homework all night. Then again, I would feel equally stressed counting the ticks of the clock on my wall and realizing I was off by two seconds. My parents had no idea that it was not only schoolwork that left me losing control of myself.

I share these experiences, because growing up like this, I did not think I had a mental disorder. When people joked that I had OCD because I was so organized, I believed that that was all that OCD was, and that it was casual. I did not know the real terror behind having a panic attack. Basically, I did not know what any of these labels actually entailed until after I had gone through it all.

So I share, because I want to start another discussion about mental health. I can not only emphasize its importance, since it is often overlooked, but I want to draw attention to the worldwide understanding of what it means to have poor mental health, or an emotional or behavioral disorder.

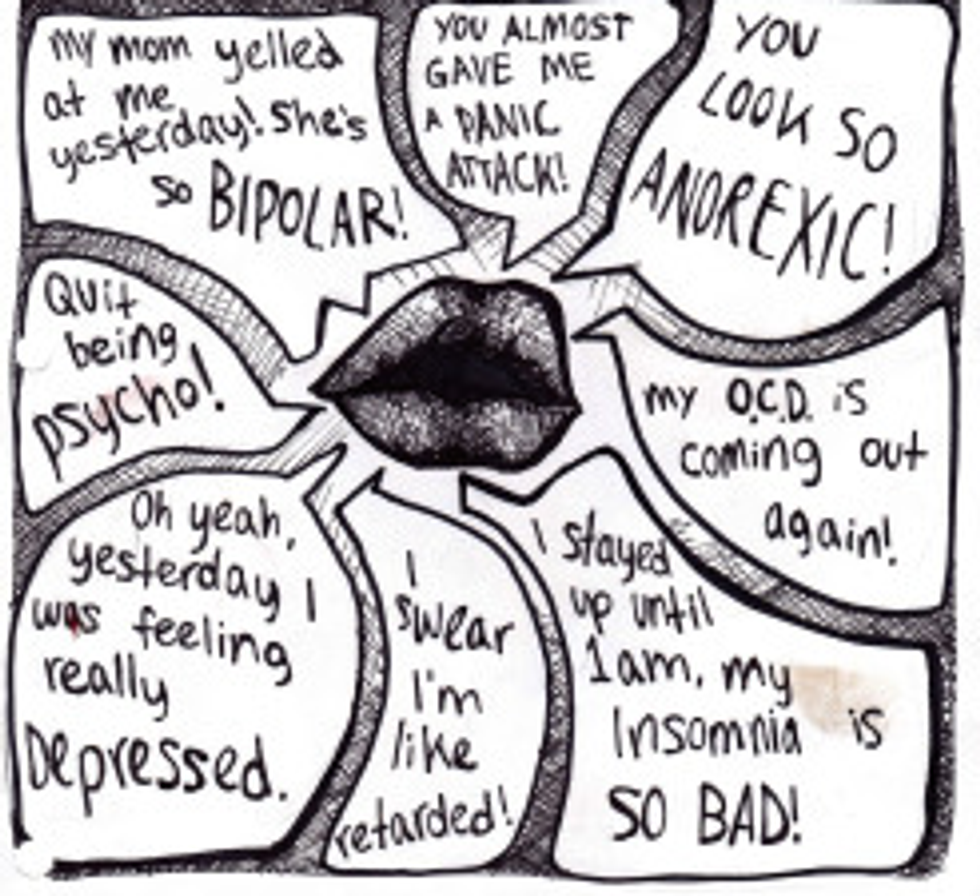

Too often I have heard people throw disorder diagnoses around like they’re a colloquialism. Having Obsessive Compulsive Disorder has become synonymous with being organized, and having “panic attacks” and “anxiety” is often associated with short term-stress that is very different from what chronic anxiety disorder actually is. Someone is called bipolar simply because they are indecisive, or ADD because they are more active. This leads to people self-diagnosing themselves without realizing what kind of statement they are making about themselves.

I think it is time for our generation to review what it actually means to have a diagnosis of a mental disorder. The overuse and the way I have heard people use these terms so casually, as if they are almost cool, has me wondering if society has actually made any progress in the ways of mental health.

Poor mental health of any degree is not cool. It does not enhance one’s self-image. It is hard, and changes every part of your day-to-day activity. Using a label of a mental disorder does not make you seem more relatable, more dark and mysterious, or more fashionably unstable. Instead, you label yourself with a diagnosis that many people are struggling to change.