For the first time in several years I decided to clean out my closet; the jumble of t-shirts and jeans and unworn sweaters from Christmases past had become too unruly for even me to ignore. The task sent me on a nostalgia trip, as I pulled out old clothes I hadn’t seen for years— because, of course, only I would feel a sentimental longing for ratty Old Navy tees and Aaron Rowand shirseys. But cleaning out my closet also served as a stark reminder of how far I had come. Most people will go through old clothes they wore a decade ago and pine for the days when they were a size or two smaller; few people find themselves holding up a faded hoodie that would be two sizes too large for them today— let alone someone that is only nineteen years old. But there I stood, staring myself in the proverbial mirror, realizing that I wore men’s XLs by the time I was nine and that I wouldn’t even reach my peak weight for another five years.

On January 1st, 2011, I weighed 243 lbs— and I was not yet fourteen years old. I had been obese for as long as I could remember. When I was young, my parents had me tested for thyroid issues and the like, but the tests always came back just fine— it was, I suppose, simply a matter of poor genetics. I was rarely made fun of for my weight, or anything else for that matter, aside from a few occasions sprinkled throughout elementary school. In fact, I was rather a popular kid. But that didn’t prevent me from feeling perpetually terrible. I was never one to get caught up on another’s opinion of me, which most people would think is great; however, I was my harshest critic. I didn’t care that I was well-liked. I cared only about what I saw in the mirror.

I couldn’t stand looking in that mirror; I couldn’t stand buying XXL shirts or 40-inch-waist pants any longer; I couldn’t stand the thought that I could be such a better person, but my insecurities were holding me back. I felt that I didn’t even deserve to pursue the things that made me happy. I had so much trouble speaking up in groups or asserting myself amongst my friends; I hated having eyes on me. I will not even begin to describe the embarrassment I faced talking to girls, or, rather, being too scared to do so. I remember thinking to myself that I could not speak to girls— that I was too much a “monster.”

This feeling was not unique to me, I know. And, if anything, thinking oneself a “monster” because of his or her weight is likely a growing phenomena. Over 69% of Americans today are overweight— and an astounding 35% of the nation is obese— many of whom are children. The state of the nation’s children is particularly alarming; there’s a reason why childhood obesity is being labelled an “epidemic.” Although I do not mean to undermine the plight of adults who suffer from the physical and mental consequences of being obese, the effects being obese has on a child can be absolutely debilitating, potentially stunting the growth of critical social skills and contributing to low self esteem and depression.

To be blunt, it sucks growing up an outsider; it sucks even more growing up a fat outsider. But, unfortunately, most obese children are, to an extent, isolated. That’s what happens when you look like a giant and intimidate your classmates; that’s what happens when you’re too slow to be good at tag, or football, or whatever else all the other kids are playing during recess; that’s what happens when the nurse and gym teacher tell you about this thing you’ve never heard of called a BMI, and apparently you’ve failed whatever it is— it was a test?— for no other reason than you’re larger than everyone else. And then, after all this, you no longer make eye contact with the other kids any longer— why would they want to look at you, after all; you stop speaking up in groups— why would they want to hear you, either; you stop going to pool parties, just so you don’t have to take off your shirt in front of anyone else. In short, you stop having a childhood. You become a monster in your own eyes.

But because it’s your own self-perception that hurts the most, you have to find the answers for yourself, and that makes the task at hand ever more challenging. Most obesity sufferers expect to find a quick, easy solution to weight loss, or for their pain and insecurity to go away overnight, and, therefore, overweight and obese people are often complicit in their own victimization. Not only do they often do nothing to change their condition, but they also agree and enable those who would treat them poorly on the basis of their weight. I know that was certainly the case with myself for several years, and nothing changed until I finally got sick of being the “monster.”

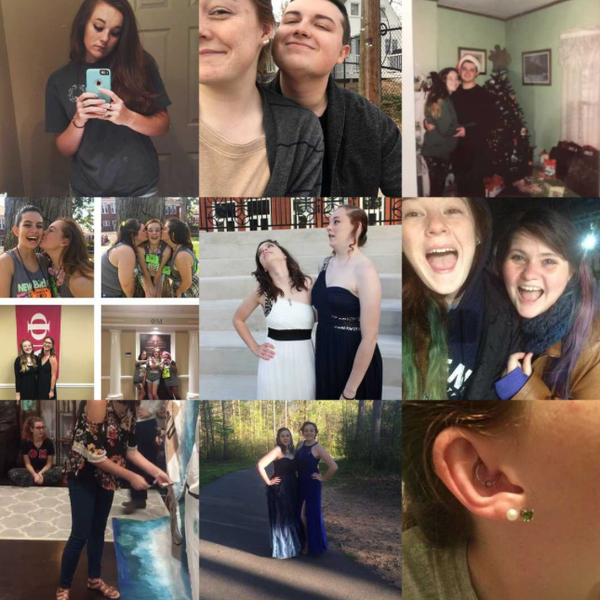

I don’t have any tips or tricks on how to lose weight fast. I don’t remember if anything specific motivated me to abandon the passive, self-loathing boy I had been and become more proactive. I just know one day I decided I was no longer going to be embarrassed by my appearance, and that by September of 2011, I weighed only 177 lbs. I— a fourteen year old with no resources or outside help— was able to drop 70 lbs within nine months through diet and exercise alone. And if I could do that, then nothing prevents the millions of Americans dissatisfied with their weight. It was starting the process that proved to be the hardest part. But once I did I was well underway to becoming a healthier human being, and maintaining a fit lifestyle soon became second nature. It’s not that hard to find an online calorie calculator or set aside an hour a day for cardio and resistance training. That’s all I did; yet, I understand it’s not so easy for most people.

Pledging to lose weight is likely America’s least kept promise. Millions of New Year’s resolutions are made to shed those few extra pounds— and then given up on within the very first month. In the epoch of instant gratification, it is nearly impossible for most people to give up a burger today or soda tomorrow for a flat stomach six months later. But this is also the social media age; your mom’s Facebook photos will be sure to let everyone know you put on a few pounds during the family vacation. Americans dread the inevitable days when the scale shows no improvement, the nights spent at home while their friends go out for happy hour and endless apps. They doubt whether it’s really worth the physical and mental effort necessary to shed those extra pounds, but they know they are not satisfied with their current condition. They get bogged down in a cycle of procrastination and depression; for them, nothing changes.

As I said, I cannot promise any easy solutions or can’t fail advice; if you’re one of the millions who struggle with your weight, then you have to find what diets, workouts, and lifestyle changes work best for you. But I can promise that if you decide to start today working on yourself today, then your life, in many ways, will change for the better. I’d even wager to say that, in a few months’ time, you’ll probably be cleaning out your closet, too.