Our lives run, mainly, according to a pre-set pattern or schedule. Think about this morning when you first got out of bed. You probably did some combination of the following: brushing your teeth, washing up, getting dressed, eating breakfast, etc. These actions may have seemed automatic, which shows, interestingly, how our brains and their neural processes prompt us to engage in certain behavior.

Neuroscience and psychology combine to inform us of the nature of habit formation and behavioral change. Charles Duhig, in his bestselling book "The Power of Habit," explains the mechanisms that drive habits by utilizing a variety of anecdotes as well as research studies. He identifies the general format of the habit cycle, which he refers to as the “habit loop.” A habit begins with a cue which triggers one to engage in a routine. This then leads to a rewarding experience, reinforcing one’s desire to continue doing their habit.

A lot of habits can be maladaptive, though. Those who suffer from addiction, in fact, mimic a similar behavioral cycle to that described by the habit loop. The cue for someone with a history or predisposition to alcoholism, ranges from experiencing a stressful event to simply going out with friends to a bar. The cue sets one up to engage in their routine of drinking in order to feel the pleasurable effect of alcohol.

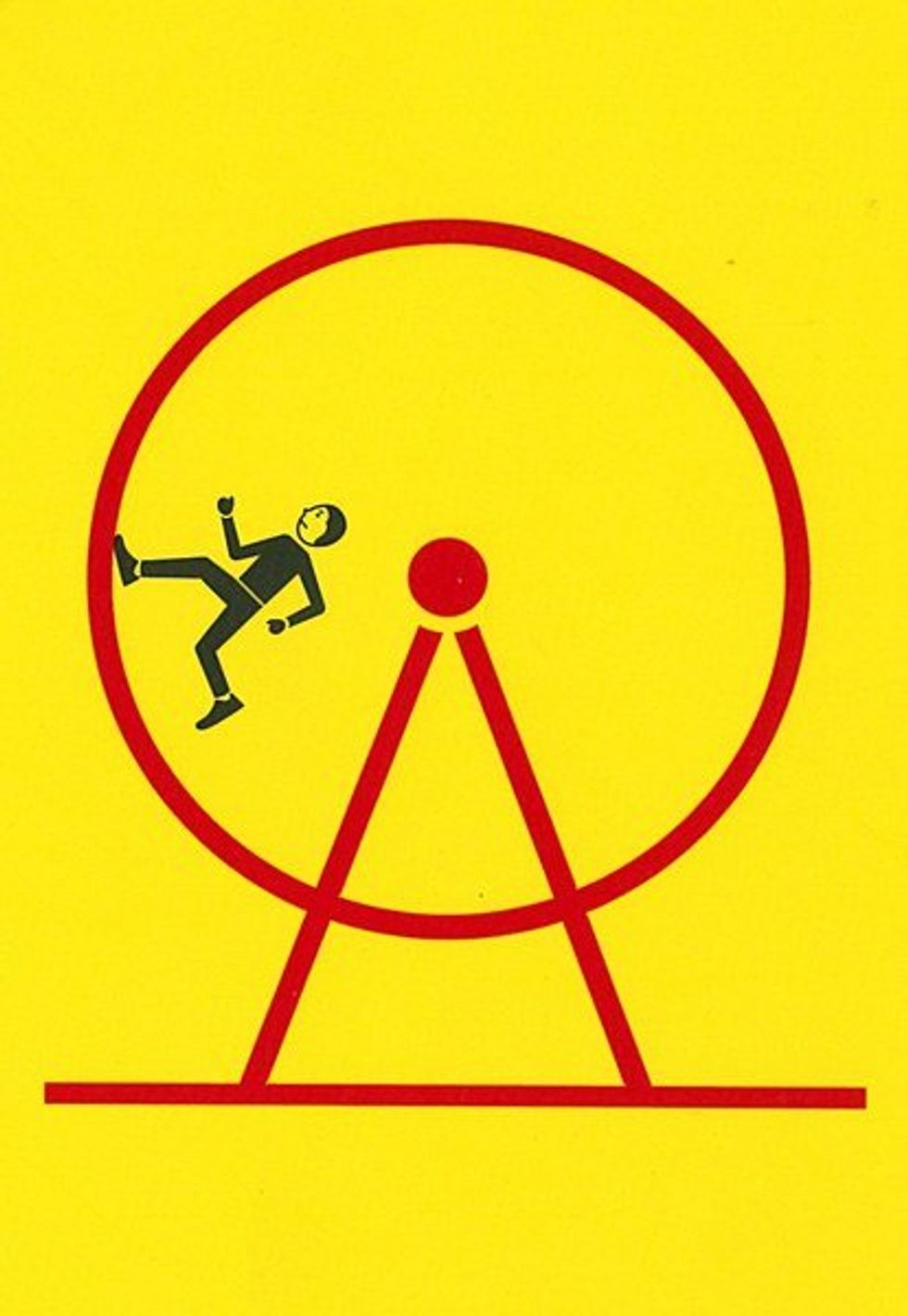

In order to break a habit, one just needs to establish a different routine that, also, leads to a rewarding experience. While theoretically, habit change seems simple, in reality it’s not so clear cut. Many people find habits hard to break, so the method that enables one to quit is more complex. Even those who recover from addiction are still at risk for relapse and can return to a habit loop of destructive behavior.

The longer one does a particular habit, the harder it can be to break. Recent discoveries in neuroscience, though, support the idea of neuroplasticity. Researchers have found that the way the brain is wired can change as one learns and practices new skills. A major barrier in the quest to break bad habits is, often, a person’s own self-doubt. Many don’t believe that they can change. Duhig notes, however, that the support group, Alcoholics Anonymous, installs a system of belief for recovering alcoholics by emphasizing the importance of finding a higher power. The effectiveness of Alcoholics Anonymous may, therefore, be attributed to its focus on renewing members’ sense of belief.

So, the phrase “believe in yourself” might not be such fluff after all.