We’re all guilty of it from time to time, and it’s nothing new. Since college athletics became nationally relevant, there has been widespread controversy over the privileges and treatment college athletes are perceived to experience, especially at larger universities. Unfortunately, most of these complaints are the result of misconceptions that are either skewed by bias or are flat out untrue. Here’s a list of three of the most common complaints and the reasons why we shouldn’t be so quick to jump to conclusions.

1. "They don’t have a right to complain; their lives are so much better and easier than ours."

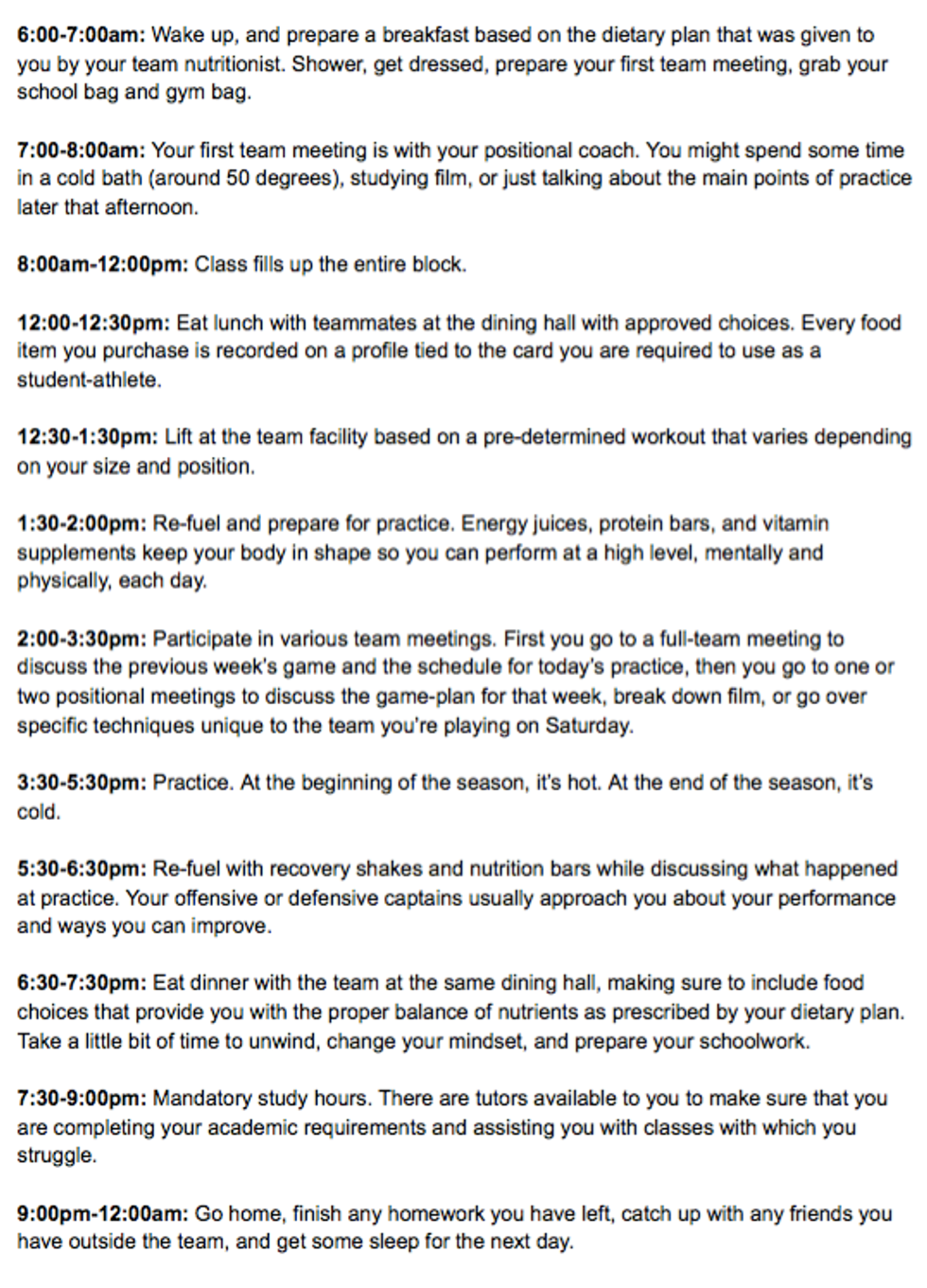

There’s no doubt that maintaining a schedule in a program, such as honors engineering, is a feat within itself (one at which I certainly wouldn’t be successful), but it may not be as different from the average schedule of Division-1 football player as you think it is. This is what such a schedule might look like on a given day, based on my conversation with a football player at the University of Tennessee who wishes to remain anonymous:

Image Credit: Mason Fleisher

You can check out a full story outlining the narrative of a few college athletes here or read a vintage one about the time Northwestern University had to pay their football players as employees of NU here.

Of course, this schedule is bound to vary from day-to-day and from school-to-school, but the principle remains the same– these student-athletes don’t have time to do the things that most students do. This study reported by USA Today shows that college athletes in popular sports spend anywhere from 37-44 hours a week on their sport-related obligations (despite NCAA rules) and an additional 32-40 hours a week on academics, depending on the sport. On average, these people are taking on 60-70 hours a week to complete the obligations demanded of them by their professors and coaches. For at least some of them, participation in the sport is not an option; it’s the only way they can afford an education.

As a member of the ROTC program and an officer in a Fraternity, I understand the struggles of being busy, but anybody successfully managing a 70-hour week featuring college classes, homework, and rigorous physical activity has every right to voice a few complaints every now and then. I certainly like to occasionally exercise that right, so why should they be any different?

2. "They get a free education just because they can run fast and catch a ball."

“Why should I have to maintain a ridiculous GPA for a scholarship, work a crappy job, or go into crippling debt when I’m probably smarter than most of them anyway?” Nearly every non-athlete who attends or has attended college has felt this way at least once. The only problem is that it’s simply not true.

The first thing you need to know is that there are NCAA rules limiting the quantity of full athletic scholarships each school is allowed to award, by sport. You can take a look at those limitations here, but the simple version is that around half of the student athletes on a given campus are not receiving any scholarship money at all. Additionally, most sports fall under the “equivalency” rule, which means that the school can elect to split full scholarships into multiple partial scholarships, leaving some athletes with very little scholarship awards at all. In other words, athletic scholarships work exactly the same way as academic scholarships; they don’t get special treatment. Less than half of college athletes actually get a “free education.”

The second thing you need to know is that they do a lot more than just run fast and catch a ball. This isn’t backyard football with the cousins or a 5-on-5 basketball league with your Fraternity brothers. According to this graphic released by the NCAA, less than 3.5 percent of high school athletes end up being Division-1 collegiate athletes. Clearly, simply possessing a natural talent to run fast or to catch well is only a prerequisite to be considered for the opportunity to play at this level, but it is not enough to get you there.

These athletes quickly become experts at their respective sports, or they don’t get to enjoy the opportunity for very long. They study fundamentals, techniques, formations, statistics, sport theory, and much more every day. They memorize strategy and team doctrine of their own teams and their opponents before every game. In some cases, they are among a shortlist of the best athletes in their sport across the nation and the world, and in all cases, they are topped in experience and skill by less than 1% of the population who play the sport professionally. If you ask a football player at the University of Tennessee for the specifics of what his job on the field entails, he’s likely to give you an answer so complicated that you’ll feel like you just walked in on a 400-level aerospace engineering class on your first day as a freshman. If you don't believe me, check out this article discussing basic defensive theory for beginner football fans.

Image Credit: http://www.knoxnews.com/sports/vols/other/more-tha...

They do a lot more than run fast and catch (or kick) a ball.

3. "They don’t even earn their degrees. They only got into this school because they play a sport."

We all know the stereotype. The big, dumb jock sits in the back of the class and skates through the semesters until he drops out or is drafted. Like the other myths we’ve discussed so far, this stereotype does exist, but, in most cases, it does not reflect reality. In reality, student-athletes are significantly more likely to graduate than non-athletes. In fact, NCAA statistics show that 80 percent of student athletes graduate, while only 63 percent of non-athletes graduate within a 6-year timespan. The National Center for Education Statistics released a report that graduation rates accounting for the entire student body of a given institution vary greatly depending on the acceptance rate of the institution, ranging from 36-89 percent, while graduation rates among student-athletes remain significantly more constant among institutions.

GPA is a different story, however. Collegiate student-athletes generally have lower GPAs than non-athletes, but it’s irresponsible to form an opinion of an entire group of people based on one statistic without any context. The New York times reported on this study done by the College Sports Project that dug deeper into the issue. This study found that male athletes averaged around .2 points lower than male non-athletes, and female athletes averaged within .1 points of female non-athletes. Institutions where the acceptance rate was more restrictive showed a larger gap in GPAs among athletes and non-athletes. A football player at Yale, for example, might have a tougher time keeping up with the academic rigors at that school than a non-athlete at the same school; that’s to be expected from somebody who works 70 hours a week! The lesson here is that there’s nothing wrong with cultivating your own set of natural talents to earn a way to reach your goals. Isn’t that the American Dream?

Image Credit: http://alchetron.com/David-Martin-(American-footba...

College athletes experience a unique set of struggles that nobody else can fully understand, myself included. Stereotypes are easy to believe when you don't have any personal experience with a certain group of people to shape your opinion of them, but it’s always a good idea to take a step back and think about things from a different perspective. Next time you sit next to a basketball player on the bus who can barely move his legs or a softball player in class struggling to stay awake, think about this article, and remember that student-athletes deserve every bit of the privileges they earn every day.