My father was a wonderful, compassionate, and intelligent man. He was a bankruptcy lawyer, meaning he worked with people who were down on their luck. I remember from a young age asking why some guy was repainting our deck. He pulled me aside and quietly explained to me that it was one of his clients who couldn’t afford to pay him in full. The man was a painter, so my father allowed the man to pay off the rest of what he owed by painting our deck. As I grew up I witnessed this happen on multiple occasions, whether it be fixing our garage door or installing a new light fixture. I realized pretty quickly that these jobs weren’t things we necessarily needed. Once I began to understand money, I recognized that the labor did not add up to what they actually owed him.

My mom told me that my father grew up incredibly poor: he was often bullied because he only had two outfits nice enough to wear to school. His father, my grandfather, was physically abusive and died from a heart condition when my dad was in his teens. My dad never had it easy, but his intellect, hard work, and resilience got him far in life. He worked his way through undergrad and law school by cleaning up the bars after closing hours; he knew the importance of an education and how it could open doors for you. He passed that message on to both my sister and me. My sister graduated from Cornell with a 4.0, and I from Villanova with a… (not nearly as impressive as a 4.0).

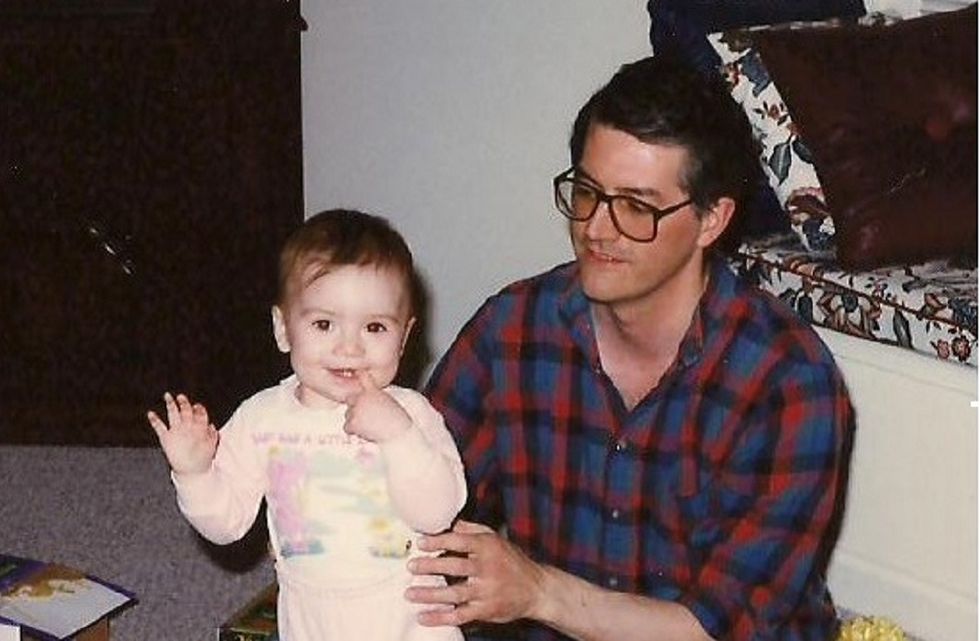

I was the youngest and a daddy’s girl; I have no shame in saying it. He tolerated watching bad horror movies with me because he knew I liked them. He introduced me to some of my favorite shows and we’d spend hours watching them together after making popcorn. Not the microwave kind either, the really good kind where you pour the kernels in a pot with oil over the stove and watch it pop. We spent weekends in the old mini-van as he taught me how to drive. Bless him because mom knew better than to get in a car with me driving. Villanova was his alma mater, and I couldn’t even believe it when I got the acceptance letter. He never pressured me into going there. He told me I should do my research and pick the school that gave me the best opportunities, but I saw that twinkle in his eye when I walked into his office and told him I made my decision.

During my college years things took an insidious turn. At first it was just little things: he stopped texting me every morning and visiting for our biweekly lunch dates. By sophomore year he was talking in circles and rambling about things that just didn’t make sense. I’d receive phone calls where he would tell me the same story over and over again, multiple times in the same day, sometimes even during the same call. He would forget what day it was and what he was supposed to be doing. Even away at college, it become quite clear that his cognitive function was rapidly declining.

When I’d come home for breaks I’d still be greeted with the same amount of excitement and cheer, but I could tell something wasn’t right. While I was telling him all about school, friends, and my future career, his eyes would glaze over and he’d become confused; he couldn’t comprehend what I was saying. He barely ate and I could see his ribs and spine protruding from beneath his paper-thin skin. His face was sunken, his hair never combed, and there would always be a new injury from his blackouts: a giant bruise on his arm, a gash across his forehead, a black eye. Eventually I’d have to return to school. There was nothing I could do to stop this; we’d already done everything in our power to try to help him. So, I’d just hug him extra tight, making sure I told him I loved him.

My father was a functional- alcoholic for many years. By functional I mean he drank in the evenings, but he was able to hold a job, support his family, and help raise his daughters. However, alcoholism is a progressive disease. They say in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) that if you don’t quit you end up dead or insane, and I watched as this disease destroyed my father’s mind, body, and spirit. He was the shell of the man I once knew, but I never stopped loving him and praying he would get better.

I got a call from my dad on January 29th, 2016. He wanted to wish me a happy birthday, not realizing that my birthday already came and went the day before. He said he was so proud of me, and that I was going to make it far in this world.

“You’re going to do amazing things, I just know it. You could be a senator one day. And you know how incredibly proud I’d be? You’d have to take me to Washington D.C. with you. I’d want to see you inducted into the Senate."

He told me he loved me, that he would be sending a birthday card soon, and that he was sorry for taking time away from my birthday evening. I told him I loved him so much, that it was no trouble at all. Had I known that would be the last time I ever spoke to him, I would never have hung up the phone.

I want to make clear that alcoholism isn’t what you see portrayed in the media. It is not just the old man on the street corner chugging a bottle of whiskey half hidden in a brown paper bag. Alcoholism does not care about your age, sex, gender, race, or socioeconomic status. It is a disease that can affect anyone and can easily destroy you and those around you. The same is true for any type of addiction. My father was a lawyer, a hard worker, and one of the kindest human beings I ever met. Even when his mind was all but gone, he still loved us and he made sure we knew it. However, just like every other mental illness, such as depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder, diseases need the proper treatment. No amount of intelligence, determination, or even love can cure a mental illness.

My father saw his alcoholism how many people see it, as a moral failing and/or a lack of self-control. Both of which are incorrect. I watched as he tried to fight this disease on his own. He would white knuckle sobriety and go days, weeks, months, and even sometimes years without drinking. Alcohol is one of the most painful and dangerous drugs to withdraw from, yet he did it again and again, hoping this time it would be different, this time he would be able to stay sober. When he inevitably drank again, he felt a like a failure. This mindset of self-hatred and shame led him to believe he couldn’t let anyone in. He isolated himself. Nobody could know he was this flawed, not even his doctors. He never grasped that his drinking was merely a symptom of a much greater problem; he never accepted alcoholism as a disease. Therefore, he never reached out for help. If he had, he may still be alive today.

In future articles I plan to discuss more about the science behind alcoholism and addiction, as well as what it is like to be an adult child of an alcoholic (ACOA). If you or someone you love is struggling with alcoholism and/or addiction, please know you are not alone. Don't let yourself become isolated. Please seek out help. You are worth it.