Have you ever heard of the Butterfly Effect? For the uninitiated, it's idea that a single action, no matter how small, can create increasingly larger impacts. For the disbelievers, look no further than the history of America's highway system.

Despite being a very boring topic by it's face value, the history of highways is a surprisingly cultured one. Born as an idea in the early 1930s, it came from a gathering of the heads of various automobile industries including Ford and General Motors, with the aim of ensuring federal funding for the maintenance and construction of roads and highways. However, it wasn't until Dwight Eisenhower signed the Federal Highway Act of 1956 that the domino effect begins.

The Federal Highway Act was a monumental moment by most standards—it was a rare example of cooperation between Democrats and Republicans, it appropriated $25 billion towards the task (not adjusted for inflation) and it would vastly improve the standard of living for every red-blooded American. Before the construction of modern highway, a trip across the country by car took roughly two months (a fact Eisenhower learned for himself).

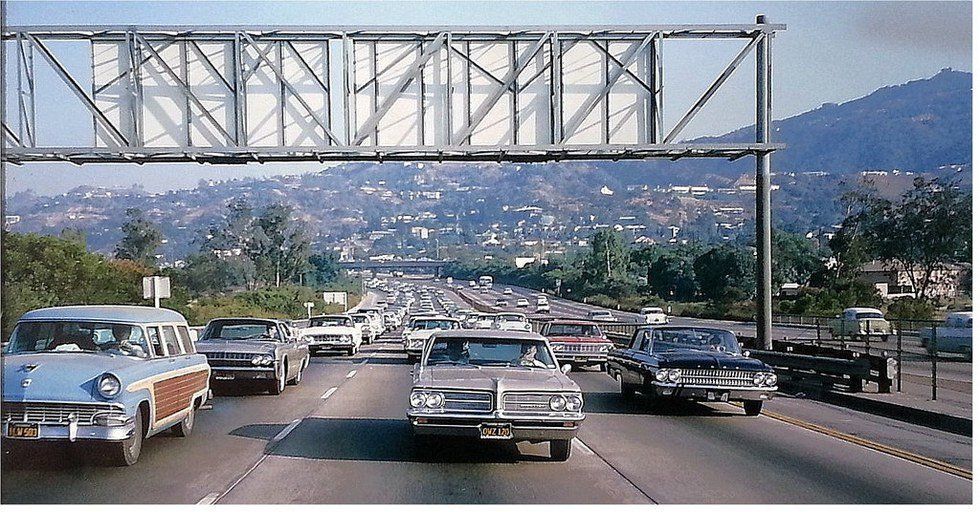

But the ripples this would have on American culture were unforeseeable. The highway cannibalized the idea of small towns built around traveled roads, and replaced it with large destination shopping centers and gas stations. It restructured American life around the automobile—suddenly far-off places were instantly available and cities did not need to be the host of residential areas as they always had been. The highway brought with it the suburbs—beautiful and homogeneous rows of easily accessible houses outside of the city. The suburbs in turn enabled the phenomenon recorded as "white flight," the mass migration of middle and high class whites out of urban areas, which were almost always racially diverse. White flight in the 1970s was actually one of the contributing factors to the economic downfall of New York City in the time.

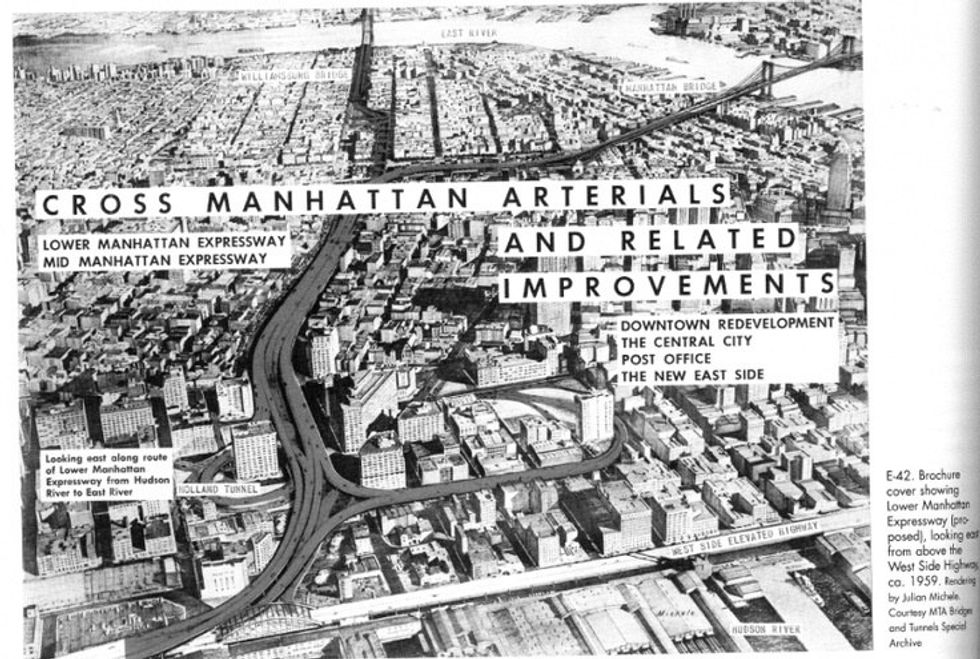

The Lower Manhattan Expressway, a failed project that would have eviscerated Manhattan's history districts.

Highway construction did not end at the city gates however, it actually was intended to cut through and bisect cities. Despite being titanic eyesores that generated unbearable noise at all hours, planned routes through cities were almost always approved. Motivation for building highways through cities is easily understood—the federal government funded a staggering 90 percent of all related projects, with the remaining 10 percent falling on the shoulders of local government. Despite this however, the question still stands—why would any city allow itself to be cut apart by a highway?

The answer is a term you might have heard: "urban renewal." If not, then perhaps "blight" or "slum-clearance." Urban renewal was the idea that within cities there were areas which fostered crime and incubated poverty, areas which were stagnant and poisonous to the city's well-being. Being a neighborhood in a city, it may seem apparent that of aid and revitalization would be the outright answer, but the prospect of highways utterly threw those ideas away. Instead of injecting these areas with the help it needed, it was much easier to simply demolish them altogether.

Demolition became a mask worn by racist intent to re-brand itself as modernization. In countless areas across countless cities—Cambridge, MA; New York City; New Orleans; Detroit; Washington D.C.; Baltimore—historically black areas were directly targeted without explanation. Historically African-American communities, some of which bore thriving economies, were selected as being the necessary sacrifice for the great American expansion.

Black communities were not targeted alone however, blight became a term that could be stickered onto anything that needed to be targeted for removal, which included Mexican barrios or even industrial neighborhoods with little to no real estate value such as the pre-developed SoHo in New York City. The reason SoHo and her contemporaries still stands is simple: political capital.

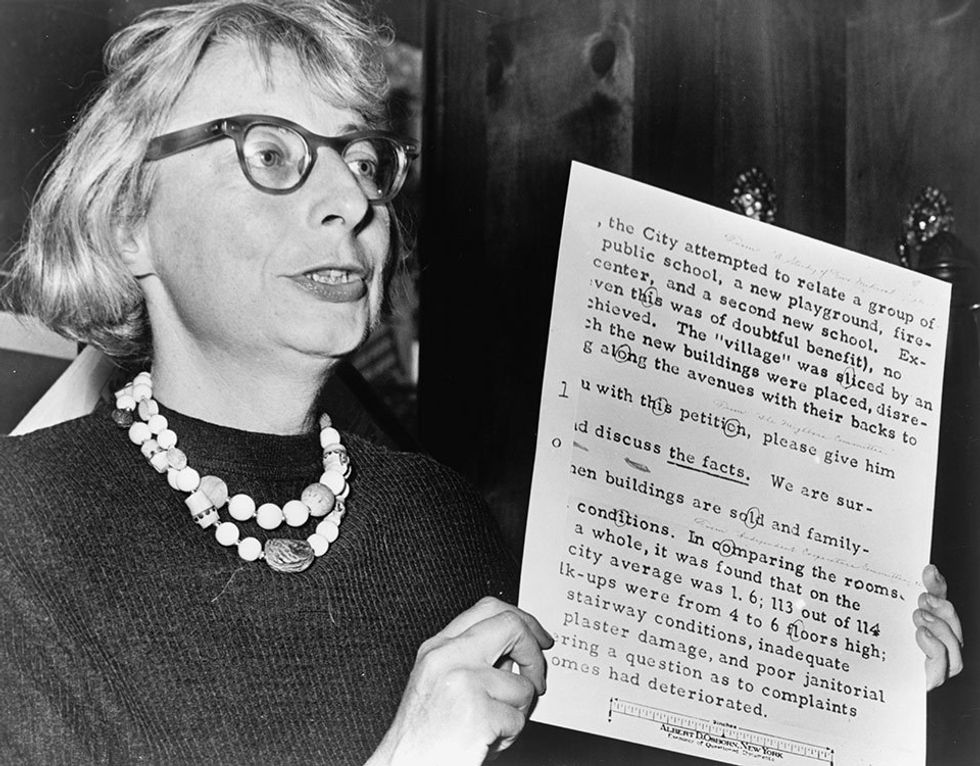

In many neighborhoods targeted for demolition with more affluent denizens, protests and political blocking were used incessantly to ensure the survival of such areas. This simply was the not the case for many countless African-Americans, whose voices went unheard against the ears of their oppressors.

For every action there is a reaction, and many of these reactions can never be predicted. But equally noteworthy is how many reactions can be predicted, how many reactions are directed by human intent, and how often that intent is ill.