One day, in 2004(ish), I was jumping up and down on my bed to No Mercy’s “What Is Love” (I was a huge Chris Kattan fan back in the day). I was so busy jamming out, that I didn’t even consider the fact that my mom would have absolutely killed me if she had caught me. Looking back, I don’t think she would have even been mad about the whole jumping on the bed thing. I think she would have been more angry that I stole her CD.

Luckily, I wouldn’t have had to worry about her killing me because I almost beat her to the punch. As an already klutzy person, I should have known not to combine my clumsiness with risk; I mean, I can’t even walk to the post office without having a near-death experience. Long story short, I ended up falling off of the bed, and I split my lip open on the edge of my dresser. My dad subsequently brought me to the emergency room, where I received stitches for my stupidity and a blue popsicle for not giving the doctors a hard time. I then went home with disappointment in my soul, as due to the stitches in my lip, I couldn’t eat pizza for about a week.

I’m sure that we all have stories like that. We’ve all gotten sick or hurt at some point in our lives, and we have all been to the doctor’s office for some sort of mildly embarrassing, majorly painful, injury. So, what do we do when we or our loved ones are injured or sick? Well, we sign each other’s casts, we send “get well soon” cards, we take a cocktail of different medicines, we exchange “war stories” on how we got our different scars, we get better and life goes on.

That is what we do, when we or our loved ones are physically injured.

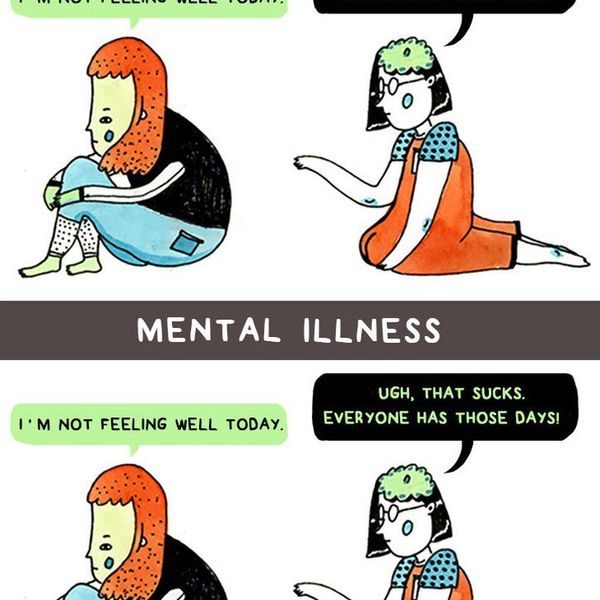

In the case of mental health, what do we do? What do we do when we feel like we or our loved ones may have a disorder? How do we help one another? How do we help ourselves? And why is mental health generally considered so difficult, or taboo, to talk about?

I spoke with Torie Keeton, who is not only one of my fabulous roommates and one of my best friends, but an extremely intelligent young woman and strong mental health advocate, who is currently taking legislation by storm (that’s my interpretation at least, I mean come on, the girl rocks). Aside from being an all around amazing student, roommate, and friend, Torie is working at two non-profits in Albany, which advocate for the state legislators in order to reform legislation and help increase mental health literacy. This increase in literacy will help people become more aware of what mental health means, and will help people recognize and prevent the various mental disorders that affect many people in our society today. The fact is, there is a lot of ignorance surrounding the issue. A lot of people use these disorders out of context. By saying you’re “OCD” because you simply like to keep your room organized, or by saying you’re “so bipolar,” when you haven’t been properly diagnosed is just wrong.

When I asked Torie how such a statement could be considered falsifiable, she informed me that statements such as those are actually “a focus of many groups trying to stomp out stigma, because when we say things like “I’m so bipolar today,” we are trivializing the struggle of an individual who truly does live with bipolar disorder. When we use these disorders tongue in cheek, it perpetuates the belief so many people hold in our society, that mental health disorders aren’t worth our worry, and thus not worth proper treatment, health care coverage, etc. We need to be cognizant of the words we use when we speak about personality traits or emotions that are a part of a healthy life. On that note, within the advocacy movement, we realize language is powerful and connotations matter. We actively replace old phrases with new ones that try to take the guilt and shame away from mental health disorders. For example, people do not “commit” suicide- it is tragically “completed.” A person is not a germaphobe- they have germaphobia. This example creates “person first” emphasis and encourages the fact that the person is more than their disorder and it does not have to overpower them.”

This is a major part of the stigma that is associated with mental health as a whole; as Torie eloquently stated, people tend to trivialize, or have a lack of understanding for these disorders. As I mentioned before, there is an air of ignorance surrounding the subject. Mental health literacy will help to reduce such stigma, as well as gain attention from the public. Torie explained to me that “with attention, it is more likely that we can begin to see changes in how mental health is regarded by insurance agencies, researchers, policy makers, program coordinators, grant writers, schools, primary care physicians, [as well as] in budget plans.”

Mass shootings are another major example of stigma gone awry. Take a tragedy, such as what occurred at Sandy Hook, for instance. In the case reports, it was stated that the shooter, Adam Lanza, had "significant mental health issues that affected his ability to live a normal life and to interact with others, even those to whom he should have been close... What contribution this made to the shootings, if any, is unknown as those mental health professionals who saw him did not see anything that would have predicted his future behavior." When I asked Torie for her thoughts on the correlations between mental health and large-scale violence, she told me that, “The number one instance mental health gets the media’s spotlight is when a large act of violence has just occurred. The fact of the matter is that it has been proven over and over again in study after study that the majority of people who are mentally ill are more likely to be victim to violence than to actually commit the act.

That being said, there is no denying that in some instances, the person who commits a crime has a mental illness-- which people are very quick to blame the entire scenario on. Moreover, they might think, ‘Thankfully that could never be my kid,’ or ‘I could never do that, because that only happens to those crazy people, not me, not my family, not my life.’ Do you see how it perpetuates the stigma? I personally think the stigma actually gives people some sort of psychological defense to justify to themselves a horrible thing won’t happen to them-- that horrible thing being a mental health disorder or, in our scenario, involved some way in an act of violence. But instead of paying so much attention to how ‘crazy’ this person is, we should be actively doing something. But the stigma takes away from being proactive. We need to be asking why that person got to the point they did. Did they receive appropriate treatment? Were they diagnosed effectively? Was their struggle taken seriously, or did we shrug it all off because they’re just being moody and they need to get over it? I think the reason we have stigma is because it is learned. It is learned by how we treat mental health as parents, educators, doctors, law enforcement officials, government agencies, etc. If we see dad rolling his eyes when your cousin is diagnosed with depression, a doctor never mentioning your emotions during annual check-ups, or overhearing a teacher saying a student needs to ‘get over himself’ when they notice cuts along that student’s arm, what is the message we are receiving? Quite frankly, that mental health is a joke, we don’t talk about it and we bottle it all up. But, if mental health is treated as a critical part of wellness and health, we will learn to take it seriously.”

So, how do we learn to take it seriously? How do we cease trivializing the matter, and how do we become cognizant of the issues at hand? As is with the cases of sexuality, race, and gender, it all begins in the classroom. Education is our largest tool in combating any sort of ignorance in this world. Torie believes that in order to make the topic less taboo, we need to realize that, “Mental health is an aspect of wellness for every individual who walks this Earth. It does not just suddenly become ‘a thing’ when a diagnosis is made. We all live in varying states of mental health, and that is what is ‘normal.’ Mental health means being able to safely manage your emotions, behavior and mindset through the ups and downs in life. Everyone deals with mental distress, and mental disorders occur in one in five individuals. It’s time we talk about mental health openly, express support, listen to hear and spread the message that there is treatment, help, support, and hope.” The fact of the matter is, we all have an equal chance of developing some sort of disorder in our lifetime. These disorders are not subjective, and just like any physical sort of injury or disease, these disorders do not discriminate. Even though we are far from implementing an “ideal” mental health care system, Torie informs me that even though it is tempting to be discouraged, change and progress are not out of the realms of possibility. She explains that mental health reform and policy, “is a movement. Advances have been made, and we are farther than we once were. I look to how mental health and mental illness is treated in developing countries, and I’m grateful for what we have as a system. I am by no means satisfied with it, but it’s what we’ve got to work with. And little by little, with each passed bill, or small research breakthrough, or child whose neighbor recognizes a red flag, or countless of other small but significant step forward, we get closer to ideal.” While working at her internships, the Mental Health Education Bill was passed by legislature, making society one step closer to achieving the "ideal" mental health care system.

Though there is still work to be done, I am confident that if there are other people on board with mental health reform, that are passionate and hardworking as Torie is on the issue, positive change is bound to happen. The bottom line is, in order for society to talk openly and honestly about mental health, change absolutely needs to occur. Disorders are not something we should feel embarrassed, or ashamed of. My biggest embarrassment from splitting my lip open back in 2004(ish) wasn’t the fact I was a total klutz listening to "No Mercy," but the fact that stitches don’t really go with glitter tees and butterfly hair clips. I guess stitches just weren’t very fashionable to third-grade Kelsey. However, that injury didn’t hold me back. I realize that splitting my lip isn’t really comparable to the disorders that affect some of the members of our society, but if you take away the specifics, I believe that it does become homologous. People didn’t think less of me for being klutzy and listening to "No Mercy." They didn’t seem to judge, or really care, they were just glad I was okay, and that I got the help that I needed. This is the type of mindset society should have about mental health. If we are not our injuries, and if we are not our diseases, then we are most certainly not our disorders. Disorders are a part of us, sure, but they don't dictate who we are. The stigma surrounding these disorders definitely do not dictate who we are. Some of the most amazing people I know have disorders, and that doesn’t make them any less amazing, or smart, or capable. Disorders do not lessen you as a person. In my opinion, these disorders can actually strengthen you. Getting the help you need shouldn’t be something to be ashamed of. Torie said it best, “You don’t have to suffer from mental illness. I promise, you can live a fulfilling life despite it.” So, let’s change the conversation about mental health, and change society for the better.

Torie is a proud intern at the Mental Health Association of NYS and the NYS National Alliance on Mental Illness. For more information, visit their websites: www.mhanys.org and www.naminys.org. If you are interested in increasing your mental health literacy, consider becoming certified in Mental Health First Aid. Find a course near you at www.mentalhealthfirstaid.org.