It was January 2015. My friend Victor, a producer I met while working on the North Carolina-shot The World Made Straight, messaged me on Facebook to say that he had been hired to work on the upcoming film by Nicolas Winding Refn.

After my face turned green and my brain partially liquefied, I asked him which limb he'd like me to cut off to work on the film. He said he wasn't offering me a job. I begged to differ.

And after three months of living in Los Angeles and a year and a half of other stuff and my name in the credits of a film that premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, here we are. I've seen the film. Instead of being a normal review (how could it be?), this is going to be an essay about my experience working on the film, watching it and my life leading up to it.

My aneurysm spawned by Victor's news comes from the fact that I was a huge fan of Nicolas's work long before The Neon Demon. (And before I go any further, I'll refer to a lot of people on their first name basis. I know it sounds pretentious, like I'm pretending to be their pal or something, but I swear it's not. People in the film industry refer to each other by their first names. It's a job, after all. You don't call your fellow associate folding hoodies at H&M by their last name, do you?) I saw his film Drive my freshman year of college in Toronto, which is kind of the perfect age and place to see it. Not only is Ryan Gosling a god in Ontario, but it's also the kind of intellectual cult film that college kids put posters of in their dorm rooms. It effectively was the Pulp Fiction or A Clockwork Orange of my generation.

He also seemed very weird.

Ryan Gosling talks about in interviews how Nicolas will cry between setups or during scenes (which I never personally witnessed), will wear a blanket around his hip to "hold his energy in" (this is true) and will shoot everything in chronological order (also true). And his media presence is very dry-humored and aloof, that archetype of the absent-minded European filmmaker with an extra layer of wit. I wondered, how the hell does a guy like that run a movie set? My friend Alex (who I think is the only other person in the world besides me that also liked Only God Forgives) asked me if I could work as an intern or assistant on any director's film, which would it be? I told him either Pedro Almodóvar or Nicolas Winding Refn.

So now it's one off the bucket list.

But about Only God Forgives, it was one of my favorite movies that year. I even dressed up as Nicolas for that Halloween. Partially because it's an easy costume (white dress shirt, shorts, blanket around waist) and partially because I like f*cking with people with really obscure costumes. But here's a pro tip. It's very weird to shake hands with someone you've dressed up as for Halloween, especially if they're wearing the same exact costume at that moment. So be careful.

Anyway, so after weeks of pestering Victor and eventually having a phone interview with the production coordinator, I was hired for the job mere hours away from a UNC-Asheville deadline that would determine whether or not I'd get my tuition money back for the semester. I quit my two jobs and drove out to California during the worst f*cking snowstorm I've ever seen in North Carolina. I also had no place to stay (I may have exaggerated to Victor the ease with which I could live in California) and was pretty terrified. When I parked my car in Los Angeles, in a sh*tty neighborhood in front of a sh*tty AirBnb, in that hot, polluted California desert air, I immediately thought, "This is the worst f*cking mistake I've ever made in my life." My feelings didn't get much better when I realized there was no Internet in my quarters so it'd be difficult to look for an apartment in less than a week and I got the first parking ticket in my life that very first day in Los Angeles.

I mention all this to only demonstrate the fact that those credits at the end of movies that people walk out of aren't just a list of random, anonymous people who had a minor hand in the making of a movie. They're almost all people who went through a lot of sh*t just to get the gig and went through even more during the gig (including, and perhaps especially, the "good ones"). The film industry is all-consuming, with 12-hour-a-day minimums for five days a week for months. And all the roles are thankless except for the actors, who have to go through their fair share of sh*t too. A movie that lasts for a little less than two hours in an air-conditioned theater or, more likely, a casual ignoring on Netflix as you browse through thousands of titles, likely caused profuse sweating and crying to at least 100 people, all workaholics and all people who don't see their families enough.

An entirely different film could be made about my experience working on The Neon Demon—the move I made after a month because I didn't like my roommate. The incredibly fun and amazing two months I spent with five roommates in a big house in Los Feliz, the movies I voraciously watched over the weekends, the screenplay I worked on in Nicolas' office in the mornings in the vague hope I could absorb some of that energy, the short film I was submitting to film festivals across the globe in my off time, the Skype sessions I had with my ex-girlfriend as she comforted me during my stress, how one of the grips called me the most important man on set on the first day of shooting simply because I brought a case of water for everyone, the ramen, taco, Ethiopian, Chinese, Japanese and In-N-Out I ate, the frenetic driving at five different points all over town getting groceries, hard drives, tapestries, and mail for crewmembers, all part of a larger network of Los Angeles people in traffic, all people with their own unique lives and stories, all people being ignored by other drivers, too obsessed with their own journeys and all too limited by the capacity of the human mind, too small to comprehend that everyone is the star of their own story and that everyone is a supporting character or an extra — but it's not what shows up on screen. And no one can judge a movie based on what its production is like. Because in the end, all my stories in Los Angeles don't really mean anything in terms of the quality of The Neon Demon. My presence certainly affected the production, of course (if I didn't work on it, I'm sure it'd at least look a little different in that alternate universe), but I was just a production assistant. No critic should or could talk about me in a review.

By the way, my job was working in the production office as a production assistant. I basically did office work like making scripts and other paperwork as well as deliver messages, as well as any other errands that needed to be done (I picked up some people from airports, made lunch orders, moved furniture, blah blah blah).

My bosses knew I was a big fan of Nicolas and would let me do a lot of the set deliveries and stick around to just watch what was going on. Nobody really understood my obsession (looking back on it, I hardly can believe my own lunacy), but that's because to many in the crew, it was just another gig. To me, it wasn't an ordinary film shoot. This was an education.

And therein lies the difficulty of viewing the film as an audience-member. If I considered the experience basically a film school that paid me, wouldn't it be awful if the movie sucked? And I was already a pretty big fanboy beforehand. But now that I had a hand in making it happen? It's crazy, right? How can I view it properly?

After all, I'd been to every set seen in the film. I own a piece of the tapestry that Elle is lying in front of in the first shot of the film. I have some wardrobe worn by people in the movie. I remember the weather during the scenes we shot it. I've danced with the cinematographer and (one of the) screenwriter(s). I read the script almost 2 dozen times because I read it from beginning to end every time there was a revision and boy, were there a lot of revisions.

But this is what I got out of it. It's not as great as Drive, and I think Nicolas may unfortunately be damned to it being his best movie. From what I gathered, it's his film that had the least amount of yes-men, which I'm sure frustrated him, but it's those parameters that made it work better. But that being said, The Neon Deon is still a significant piece of filmmaking. During some sequences, I sat in the theater completely flabbergasted, thinking, holy sh*t, I've worked on something monumental. And I'm permanently etched into it.

The weird thing about it is that I completely understand why somebody would dislike it. It was obvious from the first draft of the screenplay. Characters often seemed like stereotypes, speaking in a stilted dialogue that to some people would come off as stylish and to others as the product of someone whose first language wasn't English (for the record, two other female screenwriters with English as their first language wrote the script). But based on interviews with actors like Ron Perlman, I also knew Nicolas only used the screenplay as a rough template, even going so far as to throw it out the window if he felt the scene wasn't working. What I didn't know is that actors would say their lines and just give long pauses before and after lines. You know those weird moments of dead air in DRIVE? I'm almost certain that the actors had normal lines but Nicolas wasn't satisfied with them so he simply used the dead air that he had already filmed. It's brilliant in its own way and hilarious when looking at the raw footage.

But there isn't that much dead air in The Neon Demon as there is in Drive. Whereas Only God Forgives was almost frustratingly obtuse, The Neon Demonis very blunt. Young girls don't know what they're getting themselves into when entering the modeling industry. Women hate each other. Men are scum. Models are scum. Photographers are scum. Agents are scum. Boyfriends are scum. Only beauty can be valued in this cruel world. And if you're born with it, narcissism is a positive trait.

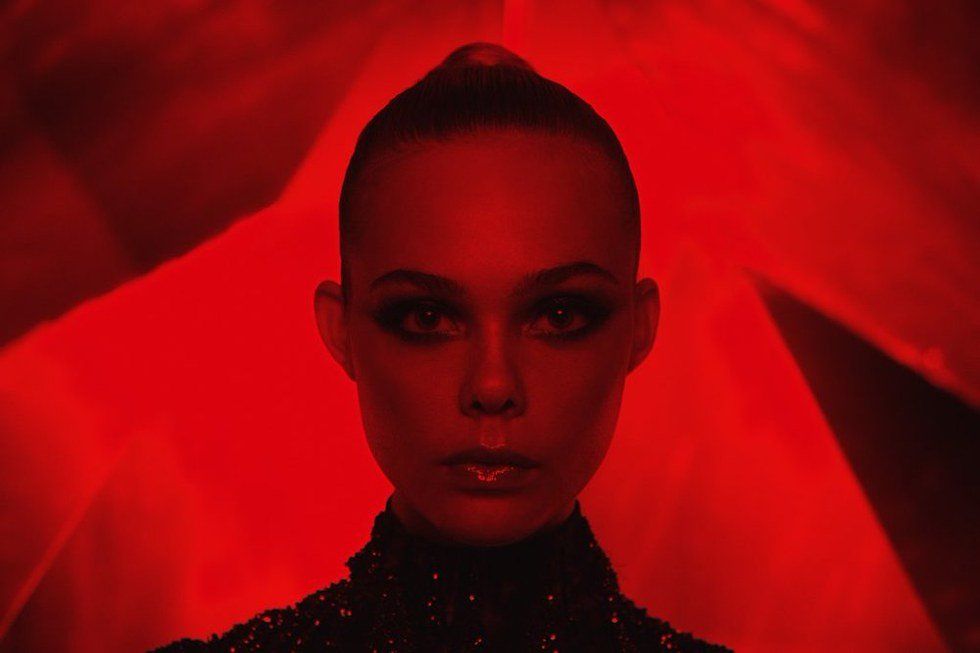

Needless to say, there's not a tremendous amount of subtlety in the film. And it plays more like a fairy tale than an actual contemporary story. Its visuals are so breathtaking that they are starkly juxtaposed against the simplicity of the narrative (Elle Fanning plays a girl named Jesse who comes to Los Angeles to pursue a modeling career but discovers a sinister underbelly). But to say it's style over substance misses the point. The style is the substance. The film is a paean to narcissism, beauty, and gloss. It's an ode to films like Suspiria (which was referenced during pre-production) and Valley Of The Dolls. It's schlock as fine art. Whether or not you can accept that will determine how much you like the film. Because it gets very strange very abruptly, and if you're not already along for the ride, The Neon Demon will spit you out.

A lot of comparisons (by people who haven't seen it) are with Black Swan, a film also about young women seeking perfection in a competitive industry. And the (failed) marketing of The Neon Demon certainly points audiences into that direction. It comes as no real surprise that The Neon Demon was pulled out of wide release after only one week, dropping out of 598 theaters. While Black Swan (which I loathe) is weird on a scale of mainstream horror, The Neon Demon is weird on a scale of arthouse films. There's almost a purity to its strangeness. To market The Neon Demon as a standard horror film is so misleading that its disappointing (USA) returns are not remotely surprising.

My point is that whenever you do see The Neon Demon, which will unfortunately not be in a theater but at home, know what you're getting yourself into. It's a very emotionally aggressive movie, the epitome of what Nicolas wanted to do in films since he first watched The Texas Chainsaw Massacre as a kid: he wants to make films that reach out and grab you and twist you. He, the cast, and crew succeeded and I'm lucky I was able to help out.