The US Constitution, drafted in 1787 and in effect since 1789, it is the highest law in the United States, since every law in the US has to abide by the guidelines set out in the Constitution. Designed as a way to outline the way the government functions, it has been manipulated, changed, enhanced, and upgraded throughout its lifetime of 229 years. Unlike regular laws, however, these changes to the Constitution are much more difficult to come across.

First, a new amendment has to be proposed in either the House of Representatives or the Senate by a member of those bodies. The amendment is then referred to a committee, where, if it is approved, albeit heavily edited and revised from when it was first proposed, it will then be passed to a floor vote. If two-thirds of the house votes in favor of the amendment, it is then sent to the other house and go through the same process. If the two versions come out and they're different in any way, another committee, made up of members of both houses, has to reconcile the differences, and then the new version is sent to both houses for a vote. Again, both houses must give a two-thirds majority (290 in the House, 67 in the Senate), and if both do, it is then sent to the states, where three-fourths of them (38 as of 2018) have to also approve them in their state legislatures. Only then does an amendment become official. In total, this entire process has reached the state legislature stage 33 times, and in 27 of those times the necessary number of states for ratification has been achieved.

However, we're not here to talk about those 27 Amendments that have already been added. No, we're here to talk about the rejects, the ones that came oh-so-close but just fell short, or the ones that went no where and never had a real chance of going anywhere. If you were proposed and never added then you're eligible for this list, so let's get on with it and look at what could've been laws of the land! In no particular order, here are 10 proposed Amendments that didn't quite make the cut.

Congressional Apportionment Amendment (proposed 1789)

The idea of Amendments was to rectify any mistakes the original drafters made or include something they omitted. In fact, the only reason the Constitution passed through Congress was because of the promise of Amendments to protect regular American citizens. This led to the creation of the first 10 Amendments, referred to as the Bill of Rights. These 10 Amendments promised protections like freedom of speech and press, freedom of religion, protection from the quartering of troops, and so on. However, what's not quite as well known is the Bill of Rights's two littler cousins. One of them, which concerned the ability of Congress to adjust their own salaries, was passed and became the 27th Amendment in 1992, despite it being originally being sent to the states in 1789. The other proposed Amendment, sent out along with the other 11, is an extremely interesting story.

The Congressional Apportionment Amendment created guidelines on how to allocate representatives to the different states so that they would be represented in the House of Representatives. As of 1792 it had 11 ratifications, one short of the required 12 to make it official, and no state since has ratified it, meaning this amendment still would need 27 states to ratify it. That is, unless we were to, say, discover a state that ratified it and its ratification went unrecognized.

Well, believe it or not, this might just be the case! In the fall of 1789 the lower house of the Connecticut State Legislature ratified the Congressional Apportionment Amendment, however the upper house refused to hold a vote on this or any of the other proposed Amendments until after the November 1789 elections and the subsequent March 1790 swearing in of the new legislators. When the two houses reconvened, the upper house ratified the CAA alongside the other 11 Amendments, and an official memo to Congress announcing Connecticut's ratification of the 12 Amendments was written. However, at the last minute, the lower house voted to rescind its ratification of the CAA. To that point in American history, no body had ever rescinded its ratification of an Amendment, so it was unknown what the process was. While the two houses attempted to reconcile, the memo was sent out but never received by Congress, and while the lower house promised a revote on its ratification, no vote ever took place.

If you consider Connecticut's ratification to be legitimate, as a handful of Constitutional scholars do, than the Congressional Apportionment Amendment was ratified by the requisite number of states on November 3, 1791, when Virginia and Vermont both ratified it. However, since legal scholars failed to recognize Connecticut's ratification, the Amendment remained unratified and unadded. Even when Kentucky joined the Union and immediately voted for its ratification, it was still one state shy and, since Kentucky's ratification in 1792, no new states have touched it. Now, if someone wanted to they could sue to have it added into the Constitution, as New Jersey lawyer Eugene Martin LaVergne tried to earlier this decade. However, US law stipulates that any lawsuit must be filed by a party with a vested interest and have received a grievance from this, which the court decided LaVergne didn't have so his suit threw out. So, until someone with a vested interest decides to stake their career on what could very-well be the most important lawsuit in American history, this Amendment, and its potential ratification, will just be left as an interesting footnote at the bottom of the history book.

Child Labor Amendment (proposed 1924)

If someone asked you if child labor was illegal in the US, then you would assure them that, of course, it was. We learn in history class that it's been illegal for almost 100 years to have children doing certain, dangerous jobs like industrial work, mining, and so on. And, yes, there are laws against child labor in every state and the federal government at-large has laws against it, there is, in fact, no Constitutional Amendment that outright bans child labor.

Now, you may be wondering why an Amendment would even be necessary, but what if I told you that the current child labor laws, at least the federal ones, could be easily repealed. Let's hope it never comes to that, but it has, at least one, happened. When the original child labor laws were passed in the early years of the 20th Century, many of the companies that employed those children sued the government for infringing on their rights. Several of these cases reached the Supreme Court and, quite shockingly in a modern sense, the Court ruled that, by interfering with commerce within a state and surpassing their right to regulate interstate commerce, the laws were unconstitutional and immediately repealed.

In the aftermath of these and other Supreme Court decisions, a mass effort to make child labor illegal in the United States began which culminated in the creation and passage of the Child Labor Amendment, which would've allowed Congress to regulate any labor done by anyone under the age of 18. 28 states have ratified it, 15 have rejected it, and the remaining 5 states (Nebraska, Mississippi, Alabama, New York, and Rhode Island) never voted on it. However, none of this would matter as, not long after the last ratification came in 1937, a new case brought to the Supreme Court considering new laws that did the same things as the old ones, was decided in favor of the government, overturning those old decisions and allowing for the government to control child labor.

To this day, the Child Labor Amendment sits unratified. If it were to be added to the Constitution, all five of the states that haven't voted on it yet would have to approve it and 5 of the 15 that rejected it would have to change their vote. It makes sense to ban child labor in today's world, but to go through such a laborious process simply to solidify a formality may be too much. If a perceived threat to the federal legislation regulating child labor is present, though, in the form of a Supreme Court willing to hear a case against the federal laws, it could be the safeguard we need as a country.

Titles of Nobility Amendment (proposed 1810)

In the early days of the USA one of the biggest threats to the survival of the young republic was the threat of outside influence on its government and citizens. Even today, we read about how other countries try and, sometimes, succeed to influence what people think, say, read, and what laws are passed. Even beyond Russian intervention in the presidential elections, governments buying ads on YouTube or holding rallies in support of their rule here in the US are perfect examples.

In the early days of America, though, we weren't as welcoming to outsiders are we are now. In fact, in 1810, Congress passed an Amendment to the Constitution that would've made a requirement for citizenship of the US that you do not have a title of nobility from a foreign country, and if you have one then you cannot become or remain a citizen.

New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Virginia voted against it and South Carolina didn't hold a vote on it, but every other original state voted to approve it. Add on Tennessee, Kentucky, Vermont, and Ohio, and the Amendment came within 2 states of being ratified. However, the last time a state ratified the amendment was when New Hampshire did so in December of 1812, over 200 years ago, so it doesn't look like this Amendment will be added anytime soon. As of this writing, 12 states had ratified the Amendment, meaning 26 more are needed to get it added to the Constitution, which I'd comfortably wager isn't happening.

Corwin Amendment (proposed 1861)

The mid-19th Century wasn't the happiest time in America. Slavery was still very much a thing in the South, the Mexican-American War had devastated the West, tribes of Native Americans were coming into conflict with the Army on the regular, and tensions between the North and South were at an all-time high. All of these factors, as well as so many others, would eventually lead to the outbreak of the US Civil War, the bloodiest war in the history of America. There were many attempts in the years leading up to the Civil War to prevent the conflict from happening. Laws were proposed, policies were enacted, and presidential campaigns became heavily devoted to slavery. Abraham Lincoln, the great emancipator, said that if keeping slavery would save the Union then he would be happy to keep it.

While none of these attempts worked in the end, there was one significant one that is often overlooked by the textbooks, most likely because of its disgusting nature. In 1861, Senator William H. Seward of New York (who would later go on to be Lincoln's Secretary of State and, in 1869, would purchase Alaska from Russia) and Representative Thomas Corwin of Ohio introduced the Amendment to the two houses of Congress, which stated that it would protect "domestic institutions" such as marriage, family conflict, and, at the time, slavery, from having Amendments made about it. It was a somewhat vain attempt, considering that the Amendment could simply be repealed or a contradictory Amendment could just be created, but it didn't matter. The Amendment was passed by Congress and sent to the states, but at that point it was already too late. Several states, including South Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Louisiana had already declared their independence.

Nine days after the Amendment was sent to the states, the Battle of Fort Sumter in South Carolina took place and officially kickstarted the Civil War. Texas would declare secession later that month and Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina would follow suit over the next few months. In total, only five states ratified the Corwin Amendment, those five being Kentucky, Rhode Island, Illinois, Ohio, and Maryland, the latter two of which would later rescind their ratification. The forerunner to the state of West Virginia also approved it but when it gained statehood in 1863 it failed to ratify it.

Later, in 1864, there was an attempt to rescind Congress's passage of the Amendment, but nothing ever came of it, meaning the Amendment can still be ratified by any state legislature that hasn't already ratified it. This means that if this Amendment were to be ratified by enough states it would come into direct contradiction with the 13th, 14th, 15th, 19th, and would overturn several major Supreme Court decisions including Roe v. Wade, which more-or-less legalized abortion, and Obergefull v. Hodges, which legalized gay marriage in the United States.

With all of that said, it would take 33 states to ratify it (35 if you count Ohio and Maryland's retractions) so odds are this isn't happening any time soon.

Equal Rights Amendment (proposed 1972)

Throughout the 50's and the 60's in America there was a social revolution. Minorities were fighting for their rights, women and their role in society was rapidly evolving, and advances in technology made it seem like the old ways of doing things were coming to an end. This all culminated in one of the most fierce debates of the late 20th Century, the Equal Rights Amendment.

The ERA, if ratified by 38 states, would have made it illegal to discriminate or favor in any way, shape, or form, on the account of gender. While seemingly popular today, there was plenty of resistance to it when it was first proposed and sent to the states. While you'd imagine many men were against it, but you may be surprised to hear there was a large number of women who were also against it. Their main argument was that women can't be given equal rights as men because if they were they would also owe equal responsibilities. In fact, this statement is accurate to a point, as many scholars have pointed out. Currently, the US Selective Service, where people are pulled from if there is ever another military draft, excludes women. Should the ERA be put into effect, though, this would no longer be the case and women could be drafted.

The ERA had a long history in Congress, finally being sent to the states in 1972. Unlike previous Amendments, though, a time limit was put on the ERA. Originally, the Amendment had to be approved by the 38 required states by March 22, 1979. When this deadline began to get close, however, and there still hadn't been enough ratifications, the deadline was moved to June 30, 1982. However, this deadline came and went and there still weren't enough ratifications. In total, 35 states ratified the Amendment, four withdrew their ratification (Nebraska, Idaho, Tennessee, and Kentucky) and one after the intial 1979 deadline (South Dakota) but that begs the question of whether or not a state can rescind their ratification of an amendment. The ERA also brings up the question of whether or not it is constitutional to put a time limit on how long states can vote on an Amendment. To challenge the idea of the deadline, two states (Illinois and Nevada) have ratified it in the past two years. If one more state were to ratify the Amendment then a lawsuit concerning the two questions posited above (can states rescind ratifications and can Amendments have deadlines) would be brought before the courts, and would likely go to the Supreme Court.

If the court decides to throw out the recessions and and the deadline, then the Equal Rights Amendment, upon the Court's decision, would be ratified by the necessary number of states and, as its language states, it would go into effect two years later. If the Court only throws out the deadline, then 6 more states need to ratify it, and if the Court allows the deadlines to remain in effect, then a new ERA would need to be drafted. Currently, there are seven states in which one house has ratified the Amendment, those states being Florida, Louisiana, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Virginia, Virginia having done so as recently as 2011. Should any one of these states, or any of the 6 that haven't voted on it (Utah, Arizona, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia) then the ERA could be back in business.

District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment (proposed 1978)

The 70's weren't a great time for Amendments, were they? In the history of the US, there have been 6 Amendments sent to the states that weren't added to the Constitution, those being the five above and this one. Of those six, 2 had deadlines put on them and both failed to meet said deadlines. Those two were the above Equal Rights Amendment and this one, the DC Voting Rights Amendment.

That's why it's concerning to hear that, when it comes to representation in Congress, the nearly 700,000 people of Washington DC have no vote. They can vote for President, yes, but that was only granted to them in 1961 with the passage of the 23rd Amendment, which still didn't give them representation in either house of Congress. They do have one representative but they are nonvoting and are not placed on any committees. Essentially, they are just an observer with no power whatsoever.

Now, there are two solutions to this problem, and both have been attempted: the first is the grant DC statehood, which the voters of Washington DC overwhelming approved in the 2016 election. However, when the bill was brought to Congress, it was referred to a committee and was never heard from again. There was no debate, no revisions, no discussion, nothing. This isn't the first time DC has gone down this route, and it probably won't be the last, but it doesn't seem to be the way to go.

The second way to go about it is this Amendment. The Amendment would do two main things: 1, it would repeal the 23rd Amendment, which grants DC exactly 3 Electoral College votes for President; and 2, grant DC full representation in the House of Representatives, the Senate, and the Electoral College. The Amendment, which had a set deadline of August 22, 1985, needed 38 ratifications to take effect. However, only 16 states (New Jersey, Michigan, Ohio, Minnesota, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Wisconsin, Maryland, Hawaii, Oregon, Maine, West Virginia, Rhode Island, Iowa, Louisiana, and Delaware) ratified it, meaning that, even without the deadline, it fell 22 states shy of going into effect. If the above-mentioned lawsuit were to produce the throwing out of Amendment time limits, there may still be a chance for the DCVRA, but as things stand now, it's pretty much dead.

DeMint Amendment (proposed 2011)

The way things are right now, to be a Senator you must be at least 30 years of age. If you're elected to that position, your term (time in office) is 6 years and you can run for as many terms as you want. For Congressman/woman, you must be 25, your term is 2 years, and, like Senators, you can run for reelection as much as you want.

Now, these rules make plenty of sense; young people are important but the older you are the more experienced and intelligent you'll be, so setting higher minimum ages and allowing for older people to remain in power makes sense. It also makes sense to allow those with experience in the position to remain in power, rather than throwing them out. However, these benefits begin to become less apparent when you hear statistics like that the average age of the Senate as of December 2016 was 61, the oldest in US history, or that the average age of the House of Representatives in 2016 was 57, tied for the oldest with 2014.

Now, when the people that are supposed to represent us get to that age, while they are knowledgeable and wise, there is a significant disconnect between them and the people they represent. A 4-term Senator (24 years in the Senate) who's 75 isn't going to relate well with a 20 year old college student from their state. As such, this creates many issues for the people, as their representatives could fail to accurately represent them, or it could even disenfranchise younger voters as they're unable to relate to the political process.

That is why, in 2011, Senator Jim DeMint, Republican from South Carolina, introduced a resolution for the creation of a Constitutional Amendment that would place term limits on Congressmen and Senators, at 3 terms and 2 terms, respectively. As these things tend to go, though, after being introduced in the Senate Judiciary Committee, it was never heard from again. No debate, no discussion, no votes, nothing. DeMint is no longer a serving Senator (he resigned and became the chairman of a conservative think tank) and, since most of our Senators are already past their second term, it's highly unlikely that any Senator would even consider reintroducing this Amendment, though it is an interesting idea to say the least.

Equal Opportunity to Govern Amendment (proposed 2003)

The Constitution has an extremely strict list of requirements for people who want to become the President of the United States. First off, you must be a natural-born citizen of the United States, meaning either your parents or one of your parents was an American citizen or you were born in America. You also have to have lived in the USA for the past 14 years. On top of all of that, you must be at least 35 years old. The youngest President we've ever had was Theodore Roosevelt, who assumed the Presidency at the age of 42, and the youngest ever elected was John F. Kennedy, who was 43.

While these rules seem to be reasonable to many people, there are some that contest them in some way. Many say that the age is too high and that it should be lowered, that way someone more representative of the population is in charge. Others say that the requirement to have lived here for 14 consecutive years just prior to your run makes no sense and disadvantages those who have to move for work. And then there are the loudest opponents to these rules; the people who want to remove the "natural-born" from "natural-born citizen".

The basic idea, for these critics, is that you shouldn't have to have been born a US citizen to be able to run for President. While there are many famous political figures that have been exempted because of this rule, the most prominent is body-builder, actor, and former Governator Arnold Schwarzenegger. Schwarzenegger, who was born in Austria, is, under the current rules, ineligible to run for the Presidency. As such, over the past several years, there have been small movements that have popped up to remove this requirement.

In actuality, though, the idea of removing this from the Constitution goes back decades, and even centuries. The most prominent effort, though, came in 2003 when Senator Orrin Hatch, Republican of Utah, introduced his Equal Opportunity to Govern Amendment. It was referred to Committee but a new Congressional term begin not long after and it was dismissed. Ten years later a new movement to have the Amendment reintroduced was kickstarted but had no effect on the legislative agenda.

So, for now at least, Arnold will just have to settle with "Terminator" reboots. Oh well.

Bayh-Cellar Amendment (proposed 1969)

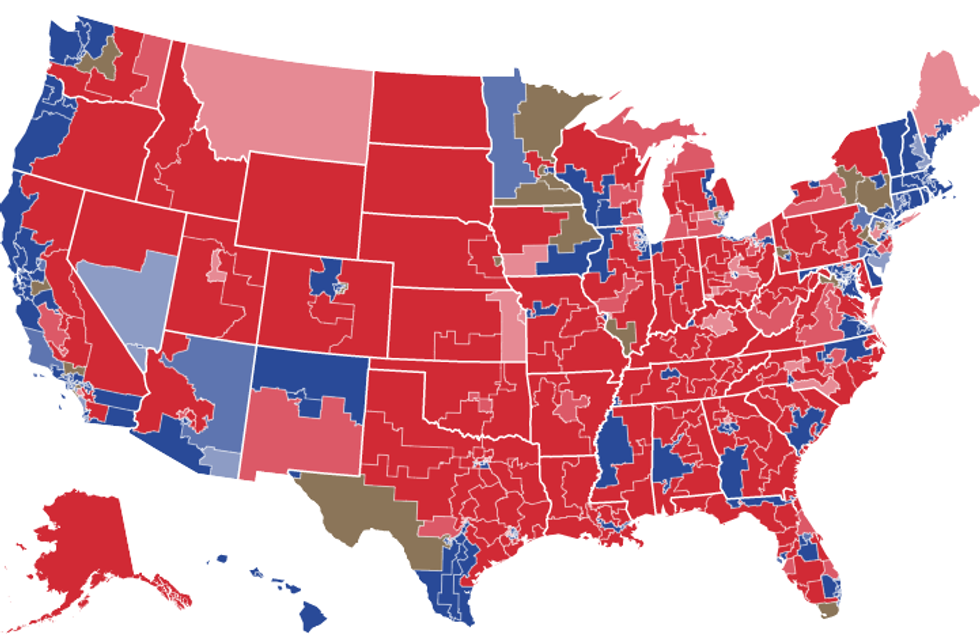

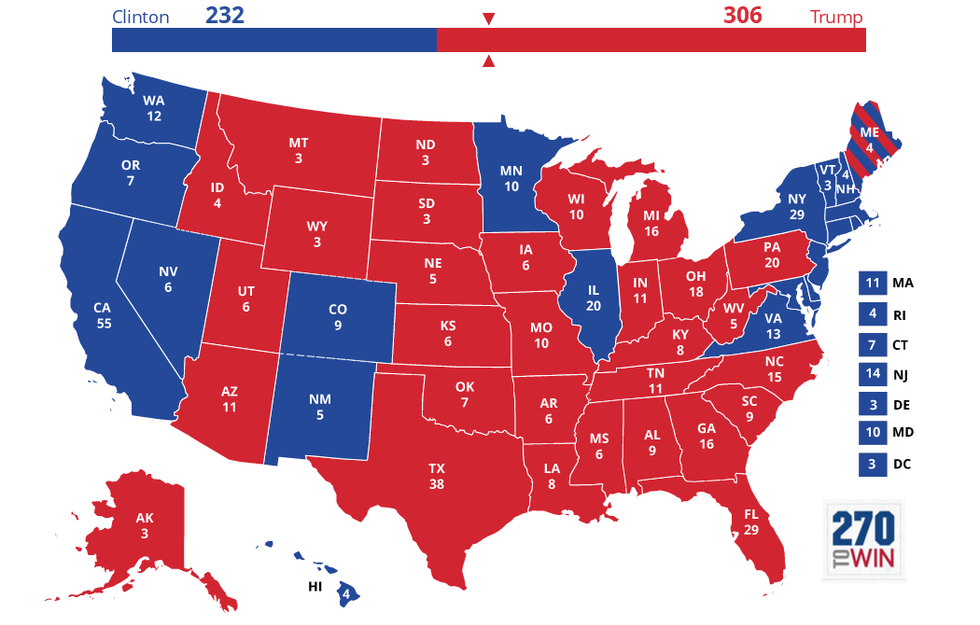

So, you remember the 2016 Presidential Election, right? Donald Trump beat heavy-favorite Hillary Clinton by a seemingly-wide margin, shown above. Trump beat her by over 70 Electoral College votes, so it looks like he won in a landslide. However, that's not the case. Per most reporting agencies both independent of and part of the government, Hillary Clinton won the popular vote in the entire US by nearly 4 million votes. So, what exactly happened, then?

Well, as I've alluded to a few times, the US uses a system called the Electoral College. Every state is given a certain number of votes for President, that number being equal to the number of people who represent that state in Congress. For example, Texas gets 38 Electoral votes because it has 36 congresspeople and 2 Senators. Every state has 2 Senators, so it's really just their number of representatives +2. The only exception to this is Washington DC, as discussed earlier, which, under the 23rd Amendment, receives 3 Electoral votes despite having no Senators and only one non-voting representative.

That means that it is entirely possible for a candidate to not receive a majority of the vote and still win the presidency since, thanks to that +2, smaller states, like Alaska and Wyoming, have a disproportionate amount of power compared to larger states, like California and New York. It's all very confusing, so I recommend you watch this video for clarity.

So, is that what happened in 2016? Trump just won the smaller-but-more-powerful states and it was enough to put him over the top? Actually, yes, that's exactly what happened, and it's not the first time it's happened. The same thing took place in 2000 when George W. Bush, then the governor of Texas, narrowly defeated Vice President Al Gore. It almost happened in 1960 when John F. Kennedy, then a fresh-faced Senator from Massachusetts, beat out favorited Vice President Richard Nixon. Other than these instances, it had only happened three other times (1826 with the election of John Quincy Adams, 1876 with Rutherford B. Hayes, and 1888 with Benjamin Harrison), and none of them were nearly as dramatic as Trump's.

With all of that said, there's need to note that there have been movements to eliminate the Electoral College since it was first used in the election of George Washington. However, none of them have gotten close to reality. That is, except for one. In 1968, There was an election similarly to 2016, where Richard Nixon defeated defeated Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey by about 110 Electoral votes, however Nixon only received a little more than 500,000 votes higher than Humphery. With the risk of another situation akin to the then-recent-ish 1888 election and worrying that the same thing could happen in the near-future (about 32 years later, to be exact), Representative Emanuel Celler, Democrat from New York, introduced an Amendment in the House Judiciary Committee to abolish the Electoral College and replace it with a popular vote system.

Unlike previous attempts to repeal the system, though, this one received significant bipartisan support, and, when the Committee passed it on to the whole House for vote, it was approved by a wide margin and was then endorsed by President Nixon. However, when the Amendment was introduced in the Senate, it wasn't quite as popular. It moved through Committee to the whole Senate, but only just barely, but when it reached the floor for debate it was quickly filibustered and there weren't enough votes to end the filibuster. The Amendment was postponed so the Senate could vote on other legislation, and was never touched again. The new term began and the Amendment died, and no effort has ever gotten even this close to this.

Should the Senate have voted on the Amendment and sent it to the states, it's likely that it could have either been approved by enough states or just fallen short, as reports mentioned that at least 30 state legislatures were prepared to ratify the proposed Amendment. However, for those vehemently anti-Electoral College will have to continue to wait.

Presidential Appointment Amendment (proposed 2003)

Many people who followed American politics in the late-Obama years and the early Trump months will recall the drama that surrounded the Supreme Court in the lead up to the 2016 Election. For those of you that didn't, I'll try to give you a very basic breakdown.

With just months before the election, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, a celebrated conservative on the court and long-time member, died suddenly and unexpectedly, leaving a vacancy on the highest court in the land just mere weeks before the Court's new session was set to begin. It didn't take President Obama long, but he did eventually nominate long-time federal judge Merrick Garland to replace Scalia. Many conservatives were angered by the move, considering that Scalia, a celebrated conservative justice, was being replaced by a centrist-leaning-left justice in Garland.

All Presidential nominations have to be confirmed by the Senate, a process we're seeing take place right now. At the time, and still as of this writing, the Senate was controlled in whole by the Republican party, putting it at odds with Democratic President Barrack Obama. As such, when Obama named his appointee and it was referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee, the Republican-controlled committee not only refused to hold a vote to send him to the Senate floor, but they failed to even hold a hearing. The Republican leadership, led primarily by Senator Mitch McConnell, Republican from Kentucky, argued that, since Obama would be leaving office soon, he should not be given the ability to name a Supreme Court Justice. It was, in fact, just a few months before Obama would leave office, however, it was not the first time a Supreme Court Justice was appointed in an election year, nor was it the closest to an election in recent history.

Eventually, Obama left office, Trump, along with a new session of Congress, was sworn in, and Trump named moderate-to-conservative federal judge Neil Gorsuch to replace Scalia. In the end, Gorsuch was passed by the Senate and assumed the position of Associate Justice, the vacancy lasting a grand total of 422 days, the longest in US history.

However, if this proposed amendment from 2003 was in effect, none of this would've happened. You see, in 2003, an Amendment was proposed that would, after 120 days, make any Presidential appointment official should the Senate fail to reject the nominee in that time. Unfortunately for Garland supporters, though, this Amendment got no further than introduction in Committee, and, as such, Gorsuch is now on the Supreme Court.

So there you have it. There are, obviously, so many more Amendments I didn't mention (there have been an estimated 11,000 Amendments proposed in the entire history of the US, only 33 have gone to the states, only 27 of which were approved by the states), and I didn't even get too in depth on these 10 I did talk about. Constitutional law is one of the most important, confusing, and controversial things in the US, as it always has been, but it's important to know how it works. I hope, at least in part, I was able to help you understand it just a little bit more. Anyways, thanks for reading and I hope you enjoyed.