If, like me, you’ve got a brain, an Internet connection, and at least one eye that works well, you probably noticed Wednesday’s Google Doodle. And if, unlike me, you don’t have a habit of obsessively researching the subjects of Google Doodles, then allow me to introduce Lotte Reiniger, the pioneer responsible for the oldest surviving feature-length animated movie, The Adventures of Prince Achmed, released in 1926. It predates Snow White and the Seven Dwarves by a decade. As added bonuses, she produced about four dozen shorter movies, about ten to twelve minutes apiece; she influenced animators ranging from premiere European animation studio Framestore to Disney itself; and ultimately went down as an exacting, premiere stylist before animation was even an establishable style. She’s worth admiring.

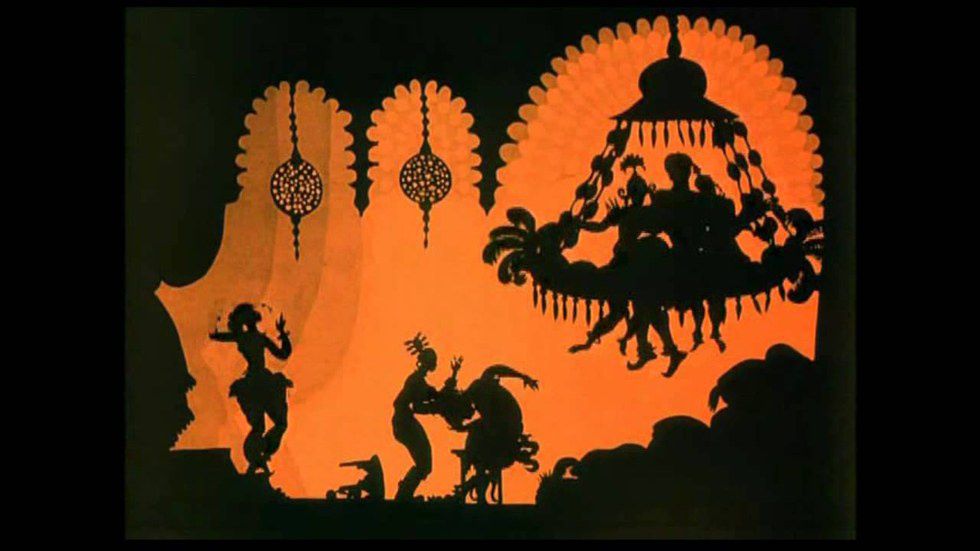

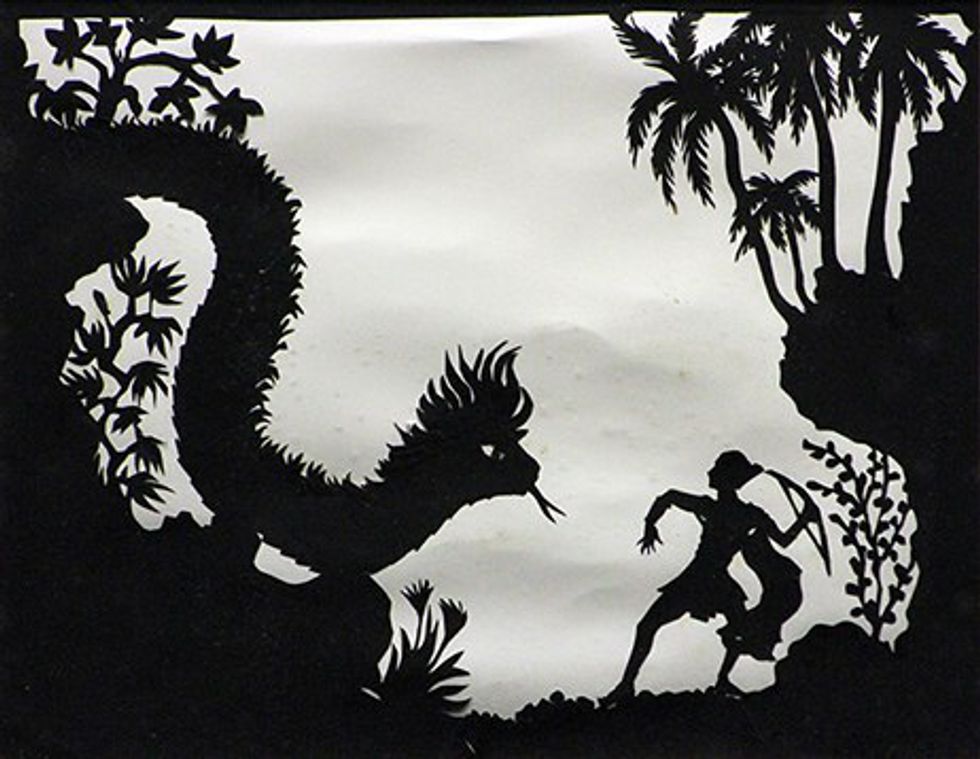

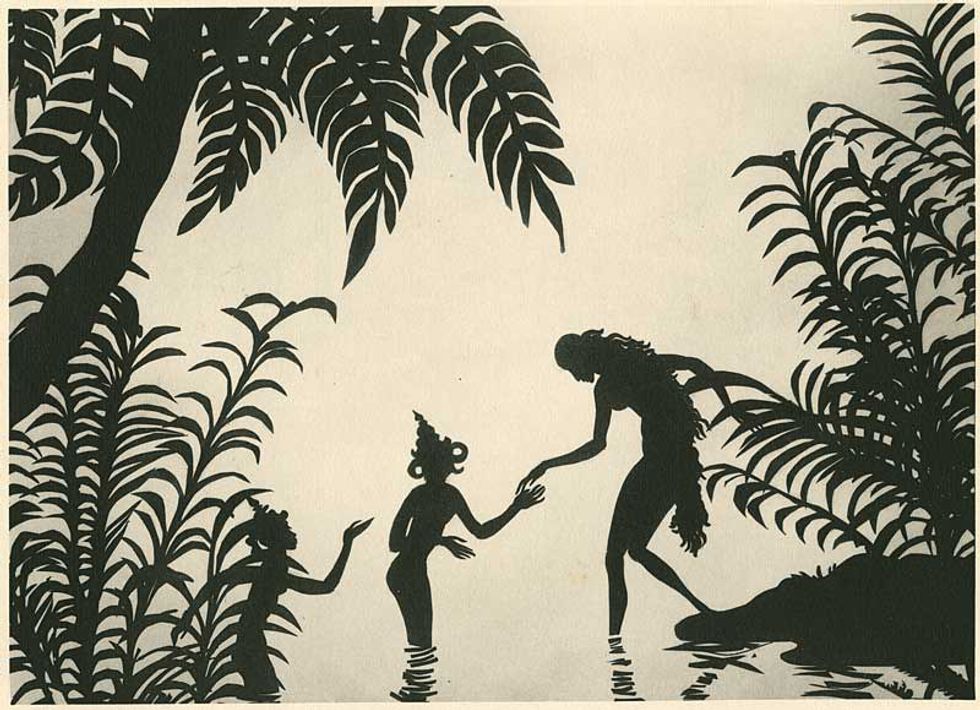

Reiniger employed “silhouette animation,” a form derivative of Asian shadow puppetry. The sheer ingenuity on display here deserves stressing. From a young age, Reiniger developed a tremendous gift for cutting out shapes with scissors, which easily ranks among the least enviable talents on the planet, right up there with competitive eating and micro-sculpture. I’ll be damned, though, if she didn’t find a use for it. One of the striking things about Reniger’s process is that, were you to attempt reproducing it, you could find everything you need in a craft store and an attic. Her animation was produced by cutting intricate designs out of black cardboard — plus some lighter sheeting to make backgrounds out-of-focus, and eventually, colored cardboards — connected at joints with metal pins, then flattened. These were in their essence extremely articulate paper dolls — paper action figures? — which could then be arranged, photographed, then moved frame-by-frame, claymation-style, on a glass table with a light underneath. From there, another especially impressive aspect of Reiniger’s movies becomes apparent: running at twenty-four frames per second, at one photo per frame, at 65 minutes in length, Reniger (alongside her husband) had to take over 90,000 pictures over the course of about 3 years.

It’s all fine and historical, of course, that Reiniger’s works were early, important, essential to the development of cinema as we know it, or whatever. It is another issue entirely whether or not her movies actually hold up. And surely, a movie that’s over ninety years old holds nothing of value to a contemporary audience, rife with the wear of old age?

(If these sound like knowingly wrong leading questions, it’s only because that’s what they are.)

The most shocking and most amazing thing about The Adventures of Prince Achmed is that it’s still gorgeous. It’s extremely expressionistic — like Nosferatu, Der Golem and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, all of which influenced Lotte — in the way it portrays the world. The movie’s aesthetic focuses on curves and sharp vertices, spindly appendages, architecture and foliage and landforms bent completely out of shape, and all nature of ribbony protrusions extending from all nature of garb. Visually, Prince Achmed is fluid and enchanting, and barely shows its age at all.

Reiniger loved fairy tales. “I believe in the truth of fairy-tales more than I believe in the truth in the newspaper,” she once said. Lots of her better-known movies tell stories that would go on to become animated classics in the repertoire of a certain other animator, including The Frog Prince, Cinderella, and The Sleeping Beauty; each predates the better-known tellings of the respective tales. Prince Achmed, too, is a version of a story from the 1,001 Arabian Nights. It follows the titular Prince as he gets lost, as we all have, after accidentally riding a flying magic horse, then flies to the mysterious islands of Wak-Wak (a place strangely absent from most modern maps), then elopes with a princess, fights a sorceror, befriends a witch, and rescues his betrothed. Oh, and there’s a brief stint involving someone called Aladdin. (The Disney Aladdin, by the way, features a character named Prince Achmed at one point, which I find poetically just.)

This is one of the great strengths of animation, and I’m willing to guess it was the thing that drew Reiniger so deeply into it. Plenty of clichés will tell you that animation can “do the impossible,” but the impossible what, precisely? Has it cured cancer yet? I think not. It also can’t tell “impossible stories” as far as I can tell — is there really any story that can be told in animation, but not in a book? If not, how are they in any way “impossible?” The actual thing animation is really great at is producing impossible visuals, and that makes it really good at producing impossible imagery. Be honest: a horse flying through the sky would look pretty silly if it used wires, greenscreen, or computer-generated graphics; but on paper, somehow, it’s way more believable. Reiniger had this pristine observation on the matter:

“The characters […] have no real existence. They have been designed and cut out of a sheet of black paper and are made to move on backgrounds lit from below and photographed from above. This brief explanation is not offered as an apology for their lack of life but to make you marvel that they have so much.” [Source]

To me, animation is a means to imagery, not looser narrative. It isn’t very hard to convince the audience that something could’ve happened, considering the rules of your story; it is hard, sometimes, to actually show it to them. Think of all the efforts in CGI and animatronics that something like Jurassic Park demanded; or hell, think of how frustrating it must be to have to have to build a canyon around the action in Fury Road without anyone becoming the wiser. Rightly, some of the images in Prince Achmed are downright unforgettable. The scene in (what I’m about 80% sure is supposed to be in) the volcano, the fight between Achmed and the snake, the descent of the birds into the lake; every last one is stunning in its own away. There’s an impressive amount of variety in the visuals to boot. The copy of the movie that circulates ‘round the web is tinted smartly (the section in the volcano is red, if you can believe it; the sections by the lake are blue; etc.). For such an early, and at the time experimental, picture, Reiniger possessed an unlikely amount of understanding for basic film grammar. And it was experimental to the point that almost no theater would dare show it. To my not-remotely-comprehensive knowledge, this makes it one of the only movies that was suppressed simply because it was too beautiful.

Reiniger was also fond of music. The visuals in her movies perfectly correlate with the scores, which she often borrowed from Mozart; but Prince Achmed uses an outstanding new score, composed by Wolfgang Zuller. I actually sought out a continuous copy of the audio online after I watched the movie to listen to separately. I’ve seen only a handful of silent movies, but Prince Achmed has helped me develop a sincere appreciation for their ability to express everything that is essential through the most filmic ways possible. Prince Achmed is visual information and sonic feeling; I find it almost upsetting that movies like Samsara and Koyaanisqatsi, however attractive to look at, didn’t bother attempting any kind of plotlines. Considering the version on YouTube has no subtitles, I had to muddle through Prince Achmed’s handful of captions via either painstaking Google (mis)translations (ew!) or through guessing. I was quick to learn that the second option works as well as the first. Putting tired adages about showing-not-telling aside a moment, I love that the movie is a plain gut-punch, where every delight is visceral and pure. Almost none of the text associated with the movie is required for it to function in the first place (although, and let’s not be silly about this: the beginning of the plot synopsis is worth reading for the sake of good comedy: “There is an African sorcerer, who is a powerful magician, and also happens to be the ugliest person in the world.” [Source])

The adroitness of Achmed’s musical match-up is especially wild when you imagine the pains Reiniger must have gone to — in addition to all the other ones — just to make things match up. In one interview, she briefly mentions the complicated mathematics that go into matching up scenes with score. Between the amount of labor, attention to detail, and real talent Reiniger invested in her films, you can’t help but feel that Prince Achmed is an attentive, talented labor of love. It’s rare to see the helmsman of a movie be so devoted not just to craft but to output. In other words, she loved her movies, and loved what went into them, and (probably) loved how they would effect people. To her, love of her work was the first step to moviemaking: “First of all, select an idea that you like to do very much, for the work takes a very long time.”

The style, if not the technique, of Prince Achmed continues to be replicated. To date, though, few of its modern impressions are worth even remembering. It might simply have to do with the cut-outs being cut out. This brings us back to the Google Doodle itself, which is all but charmless to look at, for which I blame the use of cheap, rickety Flash animation instead of actual cardboard and tacks. Of course, that would be a lot of work (heaven forbid a tribute actually require much more than a few moments’ time from an outsourced animator) but for a work-around, it’s upsetting that the doodle doesn’t move the way bona-fide Reinigers do. Actually the failure proves for me that movement is the soul of animation, and for that matter movies in general. (The difference between a boring slideshow and a great movie is, at brass tacks level, about twenty-three frames per second.) The best imitation of the style that I’ve seen is none other but the incredible Tale of the Three Brothers fable, from the seventh Harry Potter movie, which feels like a logical extension of Reiniger’s style, rather than a hopeless attempt to go back to the old ways. It’s moody and ominous; although I can’t help but wonder how much money it took to make, compared to the arts-and-crafts feel of the original Prince Achmed.

And by the way, the fact that we even have this movie to watch is incredible. The niggling qualifier “surviving” has to be applied when calling this the “first animation feature” because two other films, even more obscure, were destroyed by Argentinians for satirizing the government. The Adventures of Prince Achmed was essentially smuggled out of Germany to avoid a similar treatment during World War 2. In fact the original negatives of the movie were lost, which gives Achmed the feeling of being a fantastical ride to a far-off time and place in even more ways.

As far as I’m concerned, Prince Achmed stands the test of time, better than most other movies in its class. It’s enjoyable not “for its time,” not “considering the limitations of older filmmaking,” and not “as a piece of history,” but “as a freaking magical journey that deserves to be watched on account of being excellent.” I like Disney as much as the next guy — and remember, plenty of people are willing to spend thousands of dollars to visit a region bigger than Manhattan devoted to Disney — but Prince Achmed is probably better than Snow White, Lady and the Tramp, Alice in Wonderland, Dumbo, and some of the other classics Disney Co. has obligated us to adore. It makes you wonder what a world without Snow White might have been like: would animation have taken off, or would it be kept safely in realm of the avant-garde? The Adventures of Prince Achmed stands as proof that cleverness, a dash of distinctive style, and the ability to stand against adversity — creative, political, or otherwise — will get you farther, both qualitatively and literally, across generations, as your legacy grows.

[If you'd like to learn more about Lotte Reiniger:

Vox ]