We were hurriedly rushed into our seats. A somber silence fell over the congregants. My mother, who had never taken notes at these religious gatherings, like magic procured a notepad and pen. The elder of the congregation made his way toward the pulpit at the same pace a prisoner walked to the gallows. When he finally made it, he cleared his throat, adjusted his tie, and began to speak. I was only a child, about five or six years old, but I vividly remember the night this elder of a Jehovah’s Witness congregation trudged through a prepared speech in which he revealed that there had been an “incident” of sexual abuse in another congregation. His voice wavered, but his message was very clear, “We have the situation under control. We are going to deal with the situation ourselves. Do not worry. Do not tell anyone outside the organization about what happened.”

At the moment I had a very vague idea of what was happening, but it wasn’t until later on when I consciously left the organization that I realized: that night we were all being instructed to cover up and hide this incident of sexual abuse. I felt disgusted to have sat through that speech, even though I couldn’t remember much else about it. But it always stuck with me and left a putrid smell in the air. How was it possible that these people who claim to be mediators of God’s word conspire to hide the truth? What made them moral enough to pass judgment on the abuser if they weren’t moral enough to bring him to actual justice? These questions lingered, and I found myself studying other religions just to see how they dealt with sexual abuse. I was so certain that this was an isolated event, but what I found was the complete opposite.

In tackling the widespread epidemic of child abuse in religious contexts, one must first delve into the details of why abuse happens in the first place. While there are many explanations and theories, they all seem to boil down to two overarching themes: the power of the clergy, and the reverential respect society has for clerical authority. The clergy’s power and society’s respect for religious figures are intertwined, but each reveals their own nuances that better shed light on this issue.

To begin, let us discuss the power of the clergy. James Newton Poling suggests that clerical abuse is a great evil that requires interlocking systems of oppression. He believes that the three main oppressive systems are psychology, sociopolitics, and theology. These systems justify and promulgate clerical sexual abuse. Thanks to early psychologists such as Freud, male sexual advances normalized, while female objections to those advances are symptomatic of repressive sexual behavior, even pathological. Concerning sociopolitics, the society and culture at large is dominated by a patriarchy. “Patriarchy is a system that subordinates women to men and is enforced through a combination of forces including economic exploitation, violence and the sexualization of women." Thus, male abusers in any context are more likely to be protected from being brought to justice, and are more likely to get away with their crimes.

Combining both the psychological and sociopolitical systems, then, leads one to the theological justification of abuse. Christianity, Islam, and Judaism are all patriarchal religions. God is a male figure. All three call upon the subordination of women. When a Christian woman or child suffers abuse, they are reminded of Jesus’ suffering for the sins of humanity, and are told to suffer in silence just as their divine father did. Understanding the intersection of these three systems allows one to better understand the amount of power the clergy exercises over its people. The mind, culture, and divine book all work simultaneously to continually reinforce the idea that their abusive actions are justified. Most disconcerting is the reality that clergymen are fully aware of their power and the protections in place, thus perpetuating a toxic and dangerous environment.

Clearly the clergy exercises great power, but it is the relegation of self-agency by the society at large to church leaders that solidifies that power. Garland and Argueta were interested in clergy misconduct with parishioners. They found that abuse was a process. Most clergymen “groomed” their parishioners: expressions of admiration and concern, affectionate gestures and touching, talking about a shared project, and sharing of personal information. It can be “gradual and subtle, desensitizing the congregant to increasingly inappropriate behavior while rewarding her for tolerance of that behavior." They postulate that it is not so much the grooming process, though, that leads to sexual misconduct, but, in fact, the internalized perception that a clergymen is God’s mediator, and therefore their actions are expressions of God’s will. They allow church leaders to do and say things they wouldn’t allow others to solely because of the perceived status they have of the clergymen. Ascribing such a high status to these men (usually men hold positions of power in religious settings regardless of the religion itself), distorts and obfuscates any objective view of what a healthy relationship should be between a church leader and a congregant. The willingness to believe that clergymen are somehow “special” relieves them of any real accountability for their actions.

Simply put: clergymen gradually escalate their physical contact with a parishioner. It begins with a side hug, then a full-frontal hug, then a kiss on the cheek, then excessive touching of hands and shoulders, then holding hands, and so on. Yet, since the congregant trusts their clergyman, these affections may seem to come from humble and innocent “godly” caring. Because of this perception, many balk at the idea that their pastor is flirting or being inappropriate with them. I've witnessed a pastor flirt with a family member of mine with her daughter present. He embraced her and held her hands in what I felt was a questionable manner. He commented on her dress and how “good” she looked. I questioned her daughter about the interaction and she replied, “It’s not like that. He’s a pastor. He just does it because he loves us in a different way.” It is this flawed logic that creates social exemptions for these predatory men, reinforcing the idea that they have divine immunity and can do as they please.

Power has been the driving force behind abuse: power exerted by the church, and the power given to church leaders by society. Having a better understanding of how and why abuse happens will let us analyze in depth the following instances of sexual abuse in different religious contexts.

The Jewish culture has historically maintained a strong sense of identity and autonomy. With the nomadic mantra of “Home is where you are,” Jews have adhered to their own sets of rules and laws to keep order, regardless of where they live. These laws date back to the time of Moses, and in instances of child abuse, they may be conflict with the secular notion of justice. Neustein and Lesher interviewed members of a Jewish community where an Orthodox rabbi had abused a male child. The parents of the child sought justice through secular institutions. This angered Jewish leaders and they lobbied with the District Attorney to set the rabbi free. Even with no evidence of the rabbi’s innocence presented, the Jewish leaders were able to have the DA drop all charges. Neustein and Lesher argue that the prominence of the beth din, the Orthodox Jewish courts, coupled with a fear of causing a public scandal in the Jewish community, works against the victims of sexual abuse.

Jews have a long history of oppression, and this history has fostered a tremendous sense of mistrust for secular authorities. Any transgressions are sought to be resolved by their own means. Any transgressions are sought to be resolved by the beth din. Rabbi Mark Dratch, a leading authority on Jewish clerical abuse, believes that community members also fear putting convicted Jewish abusers in secular jails where they may be attacked and fear tarnishing a family member’s name will destroy the rest of the abuser’s family, thus making it harder for them to find potential marriage partners. Adherence to traditional ways of life have directly impeded the prosecution and conviction of child abusers. Jewish doctrine clearly places religious reputation above justice, and sets a disturbing, but all too real, precedent.

Not surprisingly, another church with strong traditional values has also struggled with sexual abuse. In Australia, the Anglican Church has suffered greatly from the epidemic of child sexual abuse. Interestingly enough, Parkinson and his team found that 75% of all complainants were male, 67% of complainants were between the ages of 10 to 15 at the time of the alleged first abuse, with 51% being less than 14 years, 11% were under 10 years, and the span of time between incident of abuse and complaint ranged between 0 and 63 years. What this study found, then, was that males were more likely to be abused. Parkinson theorizes that this is true because there are more socially acceptable instances where a male priest can be alone with a male child or teen.

This study also reinforces the idea that self-shaming plays a big role in regards to reporting sexual abuse. The majority of victims are male, and the average time between abuse and complaint is around 23 years. Thus, Parkinson and his team believe that the social and religious constructs of masculinity, and the confusion and respect the victim felt for their abuser delayed their coming forward. Even more interesting was the fact that in trying to collect as much information on cases of child sexual abuse, the church seemed to not have those records or the pertinent paperwork was inaccessible because those specific cases were pending trial and they were in the hands of their lawyers.

What we learn from these two cases is a sad truth: society at large, in tandem with religious doctrines, discourage victims of sexual abuse to come forward, and that these religious institutions exercise enough autonomy to deal with these heinous crimes usually without secular intervention. Unfortunately, when victims don’t come forward right away, the church is able to cover-up the “incident” and tries to absolve itself of any wrongdoing.

Such is the case in the Catholic Church of Ireland. According to McAlinden, “there is an enduring reluctance it seems on the part of the higher echelons of the Catholic Church, and the Vatican in particular, to admit the full extent of its historical knowledge of child abuse by clergy and its concomitant efforts to keep allegations of abuse quiet." Reluctant priests have made it a point to deny, and trivialize the nature and extent of past abuses in order to maintain a good public image. With the church having so much political power in Ireland, “the investigation of allegations of sexual abuse by clergy fell between two stools in that neither the Church nor the State was prepared to take ownership of the problem.” Hiding past sexual abuse is one form of quieting victims, but culture and religious doctrine may discourage disclosing instances of sexual abuse altogether.

“There is no normal reaction to an abnormal action.” This is the mantra that anyone who has ever worked with survivors of sexual assault and intimate partner violence are told to teach them. The abuses they suffer are indeed abnormal behaviors, and their varied reactions (suicidal thoughts, anger, distrust of the abuser’s gender, feelings of isolation, fear, etc.) are testaments to that. But disclosing the abuse remains the most challenging aspect of sexual abuse, especially for children.

“Children often grapple with whether to tell, whom to tell, what to tell, and when to disclose so as to obtain protection while minimizing negative outcomes for themselves and their families. Children frequently experience disbelief, confusion, and unreality as they try to understand the trauma they have suffered in a context in which their lives continue as if nothing has happened." What’s worse, cultural beliefs influenced by the dominant religion make it even harder for children to disclose. Arab cultures value haya (modesty) and sharam (shame/embarrassment). A child, or any victim for that matter, must reconcile the fact that disclosing would violate these cultural values and open them up to punishment for talking about a taboo subject. Other religious ideologies also follow a similar twisted logic. Buddhists believe negative experiences, such as abuse and rape, are karmic consequences. Jews contort the meaning of Lashon Hara, a prohibition against speaking ill of others, to justify not disclosing the names of abusers. Muslims may cite the fact that Muhammad married his last wife when she was only six, and that they consummated the marriage when she turned nine, to justify sexual interactions between men and young children. The same religious texts and teachings that preach a path to some form of heaven are the same ones that allow abusive behaviors to happen and provide the justifications for those who abuse.

Another component of the systemic abuse of children and teens in religious contexts is the political and legal protections churches enjoy. The First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States has been used to defend religious freedom under the Free Exercise clause. The Supreme Court ruled that any law that would interfere with the free exercise of religion would be unconstitutional, except in cases where the state can prove that the case serves a compelling state interest in a 1972 case. Furthermore, “the Supreme Court has held that the First Amendment prevents courts from resolving disputes that would require adjudication of questions of religious doctrine” in 2006. The Supreme Court then went on to say that it couldn’t be involved in any way with a church’s decision to fire a clergyman in a case in 2012. While these cases are relatively recent, they highlight the trend of relaxing legal control over religious institutions. It is no wonder then that clergymen are not removed from their post, just simply relocated. Churches are compelled to deal with instances of abuse even if they don’t deal well with them themselves. The result is a legal maze in which secular justice loses itself trying to navigate the ins and outs of legal precedents, while simultaneously trying to justify itself as the better institution to bring about justice. These legal protections are deliberately broad so as to not infringe on the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause, but it has served more harm than good by protecting sexual predators.

Another legal issue that arises is the people’s mistrust of their government. Spröber conducted a study to find out whether abuse happened more in religiously affiliated settings, or non-religiously affiliated settings. She found that rates of sexual abuse were higher in religious settings. This, she postulates, is a result of the clerical practice of celibacy among German Catholic priests. Unfortunately, regardless of the setting, survivors of abuse didn’t report it, or didn’t want to report it, because they didn’t trust the state enough to do anything about it. Church members were well aware that the government wouldn’t interfere with high-level priests, and they knew that an offending priest would be relocated before any legal action could take place.

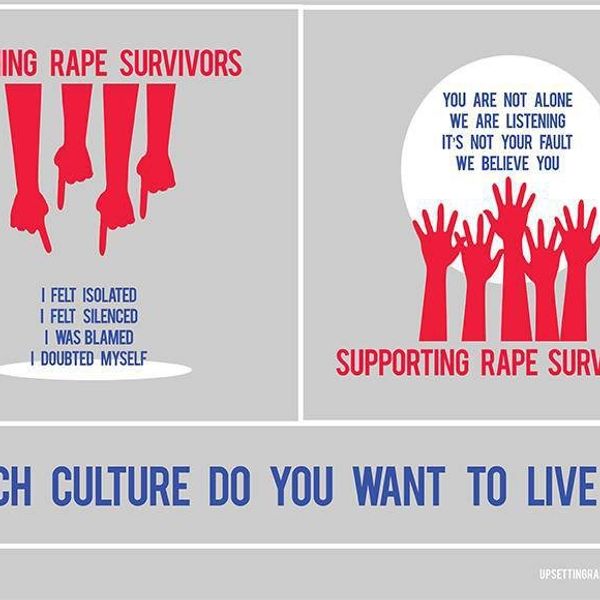

This same mistrust in the state exists in many countries, even here in the United States. It is extremely common for survivors to stay quiet about their traumatic experience because they feel that no one will believe them, they are too ashamed, and they have the very credible idea that their abuser will get away with it even if a police report is filed. As a former Crisis Counselor for survivors of sexual assault and intimate partner violence, I am very aware of the infuriating statistic that only 2% of alleged rapists will ever spend a day in jail. One cannot begin to understand the pressure and fear survivors feel after they’ve been abused, but adding the religious aspect to it understandably complicates matters.

In Reynaert’s study of adults who had been abused as children, we find that these adults suffer from some form of dissociative issue and emotional numbness. Not only do these survivors suffer emotionally, they also tend to hold extremely negative views of their bodies. This is reinforced by the Christian belief in the dichotomy of the body and soul. The body is a temporary, imperfect vessel in which the eternal, divine soul lives. “During sexual abuse, both the perpetrator and the victim use this traditional separation of body and soul as well as the objectification of the body. It provides support to the victims who undergo sexual abuse and offers the perpetrators a way to easily move into sexual abuse.” From this perspective, we learn that the dualistic view helps the survivor disassociate from their body when they are being abused, but it also, although not explicitly, gives permission to an abuser to do what they want.

Abuse as a child also impacts one’s religiosity as an adult. After interviewing a large sample of Mormon women, Pritt discovered that those who had been abused as children held extremely negative views of the church. Even more telling is the fact that survivors preferred secular therapeutic help as opposed to church-related therapy. Likewise, a study carried out by Sansone and his colleagues revealed that abuse as a child translated into more negative views of the church and also a diminished sense of spirituality. Sansone’s study also suggests that the emotional damage done to a person who has been abused may or may not detract them from the church. He found that a very small minority of respondents felt just as religious or spiritual as respondents who had not been abused. That is not surprising given that people handle situations differently.

What is significant about this finding is the all too real possibility of someone continuing their life as if nothing happened after having been abused. As stated before, there is no normal reaction to an abnormal action. Abuse is a traumatic experience that can do invisible damage. The most frightening possibility is that a survivor will not react at all to the abuse, thus making it almost impossible to tell if anything has happened. By continuing their lives in such a way, a survivor might internalize the traumatic experience and suffer from unforeseen emotional disorders or issues later on in life.

That night, the night I heard a man suffer through his own speech as if every word pulled him deeper into a moral abyss, I became conscious of religious hypocrisy. At the young age of five or six I recognized that these people were hiding behind the “God” they preached, but behind closed doors followed the rituals of the Satan they openly cursed. I am grateful for that experience because it opened my eyes to a very real reality. Sadly, an astounding number of people worldwide of different faiths blindly, and wholeheartedly, hang on every word their religious leaders utter. They are more preoccupied by what an outsider might say than by getting an abuser brought to justice. The results of the studies done are sobering. They are a reminder that humans are imperfect and hypocritical. They urge us to reconsider the pedestal we put religious leaders on and develop solid means to hold them accountable. It is disgusting and horrendous for a child to fear disclosing abuse because they will be punished. It is even viler and sickening to stand at a pulpit and preach love and peace, but do nothing to punish a man who has raped a child. Certainly not all religious leaders are rotting wastes of oxygen, but until societies worldwide start to truly hold them to a human standard and not a “holy” one, these atrocities against children will continue to happen.