Confession: last year, I stole yoga.

I’m that girl who got three yoga classes in before buying a mat and declaring, “Wow, I love yoga! Guys, I’m really into yoga right now!” and then tried to teach my friends about the wonder of savasana.

I know. I know.

On some level, it’s understandable—all I knew of yoga was what I’d learned from the trend and the photos I had liked on Instagram. I saw the practice as many casual yoga-goers do: an hour or so of stretching poses and deep breathing, with some relaxing New Agey music playing in the background. The very first class I went to was all about relaxation—we used blankets and pillows for props. (Now that I think about it, this may have contributed to why I like yoga so much.) But I had no real knowledge of where yoga came from—I just wanted to try it out.

What I didn’t realize was that my lack of awareness was a form of cultural appropriation.

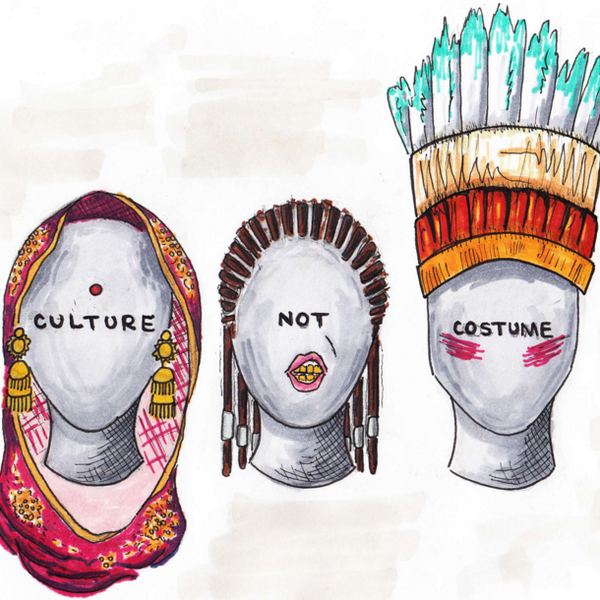

Cultural appropriation occurs when one culture adopts elements from another culture. Western culture especially has a history of appropriating beliefs and practices from other cultures, then labeling them as “exotic” and “trendy.”

However, some, like this yoga teacher, would disagree and argue that yoga is for everyone—that it’s a deeply personal movement that anyone can take part in or even a celebration of culture.

But at what point does celebration cross over into appropriation? When does borrowing from a culture become stealing?

Until I took a world religion class this year, I had no idea how important yoga is in major Eastern religions (Buddhism, Jainism, and Hinduism). Yoga is not, as writer S.E. Smith puts it, "a series of pretzel-like physical exertions done to get fit, usually with some token Sanskrit thrown in here and there to keep things exotic and spicy."

In fact, the poses (or asanas) are just a small part of traditional yoga. American Institute of Vedic Studies shows that “yoga can be traced back to the Rig Veda itself, the oldest Hindu text.” Now, Buddhists practice yoga in tandem with meditation to deepen the experience. This practice—along with other exercises and beliefs such as the Four Noble Truths, the Noble Eight-Fold Path, the Five Precepts and the immeasurables—make up basic Buddhist principles. Siddartha Gautama taught that yoga was key to reaching enlightenment and nirvana.

So is it disrespectful to try yoga without making it part of your religion? Is it wrong to go to yoga classes or follow along with YouTube yogis?

I would say no, it's not disrespectful or wrong. The problem lies, rather, in our mindset when we approach it as simply something we'd like to try out—or even adopt it as our own—without recognizing its history and deeper meaning. This is appropriation at its core.

And it hasn't gone unnoticed. Concerned with the current state of yoga practice, the Hindu American Foundation started a campaign in 2008 called "Take Yoga Back." Their goal is not to discourage yoga in Western culture, but to educate people on the true meaning and purpose of yoga.

They also raise concern about the mass commercialization of yoga, noting that studios have become "as prevalent as Starbucks" and yoga-themed gear has become not only extremely popular but also extremely pricey. Commercial America has clearly taken note of the trend, resulting in a $27 billion industry built on products like this:

And this:

And this:

And while these products might seem funny and ultimately harmless, we need to look at the bigger picture. Western culture has hijacked yoga, an ancient spiritual tradition, and turned it into a massive, commercialized movement. Like journalist Andrea MacDonald points out, “mainstream yoga has become a commodified and often hypersexualized fitness regimen, rather than a complex, life-long spiritual practice.”

Yes, yoga is a fun workout and an effective stress reliever, but we have to remember that it's so much more than that. I don't want to be a culture thief. I want to practice yoga while valuing it and keeping its integrity. That means that before jumping on the yoga bandwagon, we need to understand and respect its origins.

This quote says it perfectly: "We practice to be happier, healthier and more compassionate sentient beings—the least we can do in return is practice gratitude to the culture from which it stemmed."