Taylor Swift, at her performance at the Clive Davis Theater, said that "Blank Space" was birthed from the frustration of tabloids portraying her as a desperate-for-male-attention woman who was almost a fictional character to her. So, she decided to reclaim the narration and turn it into a money-minting, artful satire.

Her story is what I have come to comfort myself with whenever I feel my identity waning into "Ray-ah," a name that is not the one I was assigned by my family when I was born.

Initially, I was too intimidated to correct those who mispronounced my name. I only offered up my version of the pronunciation if I was asked for it. I didn't think the situation deserved much importance because it was only two syllables. Last year, someone pronounced my name correctly, said "Riii-ah," and complimented me on how pretty and pleasant the word sounded. That was the first time I felt like my name, an extension of my culture, held value; and only because a representative of the dominant culture recognized it as such. I felt disappointed at how I might have been betraying my Indian-ness for almost an entire year because I either did not think it was important or sought so fiercely to be monochromatic.

The moment I was reminded that I was a "Riii-ah" and not a "Ray-ah," that I was not a true member of American society in probably the most flattering way possible, I felt like I was experiencing an identity crisis. I had masterfully crafted a character named "Ray-ah," a student and sorority woman at an American college who morphed, over a 14-hour flight to India, into "Riii-ah," the girl who can nimbly tear a roti with one hand while biting into slices of cold, salted kheera (cucumber) with the other.

When I first returned home for the holidays, an amusing discussion with friends ensued on how our names are pronounced by Americans. I was relieved at not being the only one whose name was diluted. Sometimes, in India, I'm surprised at how easily my name seems to roll off everyone's tongues because for 8 months in a 12 month year, "Ray-ah" unknowingly begins to feel like the new normal.

People in India are no strangers to western names. We watch American television shows, read American authors' works, and listen to American music, all of which serves as exposure to a culture that is much different from our own. In high school, we were educated on African, American, British, and Asian pieces and learnt how to pronounce all the names we were unfamiliar; and the keyword is "learn," because we did not automatically know words that were phonetically unnatural to our Indian accents.

I did not, perhaps foolishly, foresee how much of my daily communication would involve explaining, and sometimes defending, my culture to the rest of the world. The format of the questions inquiring about the difference of culture carry an unfathomable flavor- "Do they not do this in India? Do they not have this in India? Do they not say this in India?" as if to say that the customs present in the U.S. are foundations and anything else is exotic- if it serves the dominant culture, like Starbucks' "chai tea"- or simply foreign and separate.

To avoid constantly feeling isolated the moment my accent runs free, I created a communication code that allowed me to quietly embed into American culture, whether that meant avoiding the use of conversation fillers such as "na" and "arre," words that are so characteristically Indian, to responding to my new name.

I did not realize how much of an identity crisis name mispronunciations create until I saw it in Chinese students who take on western/American names because their original ones have been decided too difficult to "deal with," as my tutees in the writing center have told me. Being deemed too troublesome to work with, from the moment someone hears your name, is immensely dejecting. A pronunciation that is "close enough" is never truly close enough.

I hate being called "Ray-ah." It is not my name. When I am "Ray-ah," I do not hear echoes of my mother's voice nagging me to pick up clothes off the floor. I do not feel the depth of my father's voice scolding me for not renewing passport; and I do not see my brother's angered face calling me "Didi" (elder sister) in an argument over the T.V. remote.

So, ask someone with an un-American name to teach you how to say it. Ask a non-native with an American name what their name is in their native language and if they would prefer to be called that. Ask questions, however ignorant you think they might be, because it displays an effort to learn more.

Questions create space for difference. Give someone with an unusual name the confidence to upload their linguistic and cultural identity. Allow someone the opportunity to correct you.

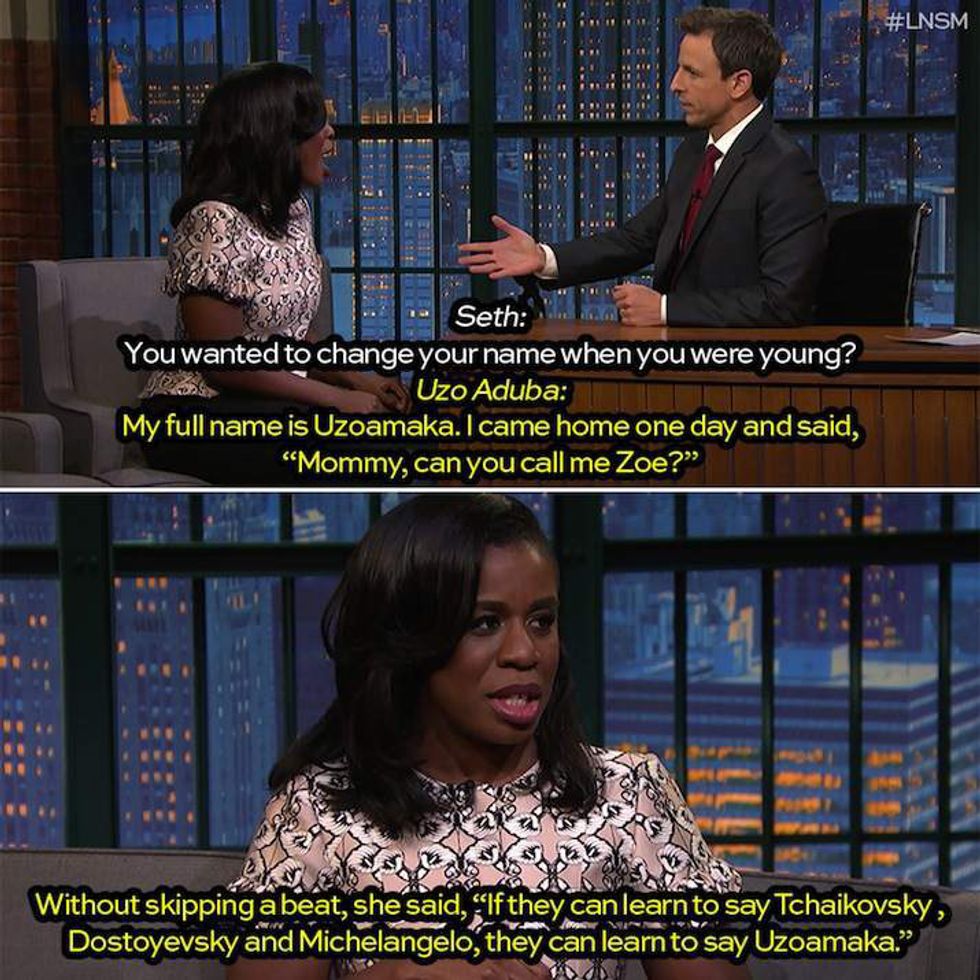

Honor their cultural legacy and celebrate the difference because, as Uzoamaka Aduba says, if you can say "Michelangelo" or "Tchaikovsky," you can learn to say "Rhea."