In 1981, Taiwanese endurance artist Tehching Hsieh ventured out into the streets of New York and proceeded to live outdoors for a full year, ending the piece (aptly titled Outdoor Piece) in 1982. In this yearlong derive of sorts, Hsieh essentially takes on the identity of a homeless individual—although “houseless” would be a more apt description of his type of purposeful displacement—calling into question tensions between public and private spaces and their impact on our everyday lives, as well as the way in which public spaces are navigated on a daily basis. Without a foil, this piece can seem only minimally problematic upon first glance, but when one simultaneously considers the series of crawl pieces performed by visual and performance artist William Pope.L, the privileged perspective from which Hsieh seems to appropriate homeless life rather than create an intervention around it becomes far clearer. While the hegemonic structure that Hsieh works within functions well as a form of de Certeau-like poaching when critiquing institutional rigidity (like in his earlier Time Clock Piece), it fails as a platform for discussing public spaces and their effects. His life simply takes on a different form, invisible to others. Pope.L, on the other hand, manages to make a spectacle of sorts surrounding homelessness and its invisibility in the public sphere by making it urgent, confrontational, and unavoidable, provoking real conversation and thought surrounding an otherwise unknown perspective.

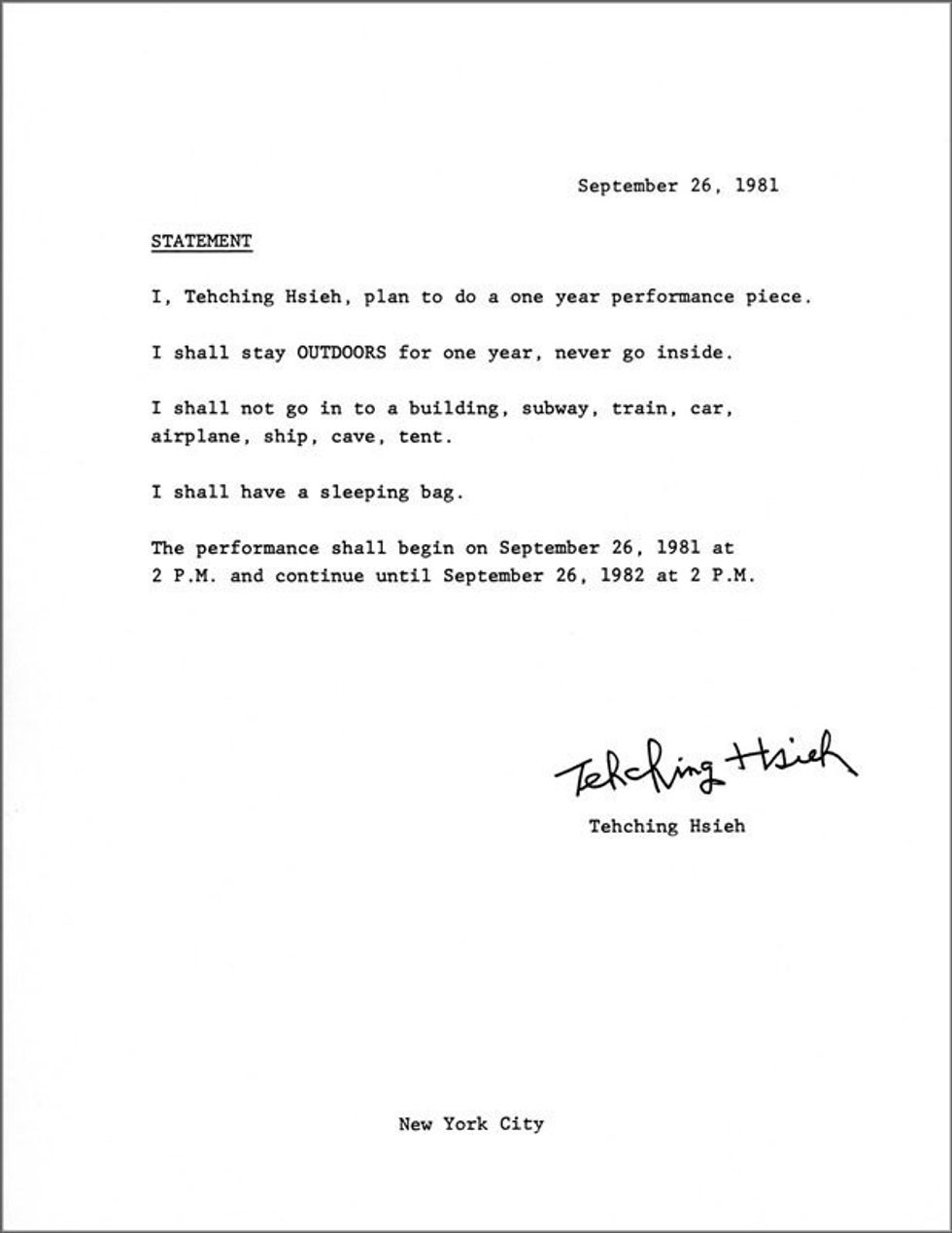

As aforementioned, Outdoor Piece consisted of Hsieh living outside for a full year in the city of New York, never entering into any building or shelter (this includes all forms of transportation besides walking) and roaming the streets with a backpack—that had his mission statement affixed to it—and sleeping bag.

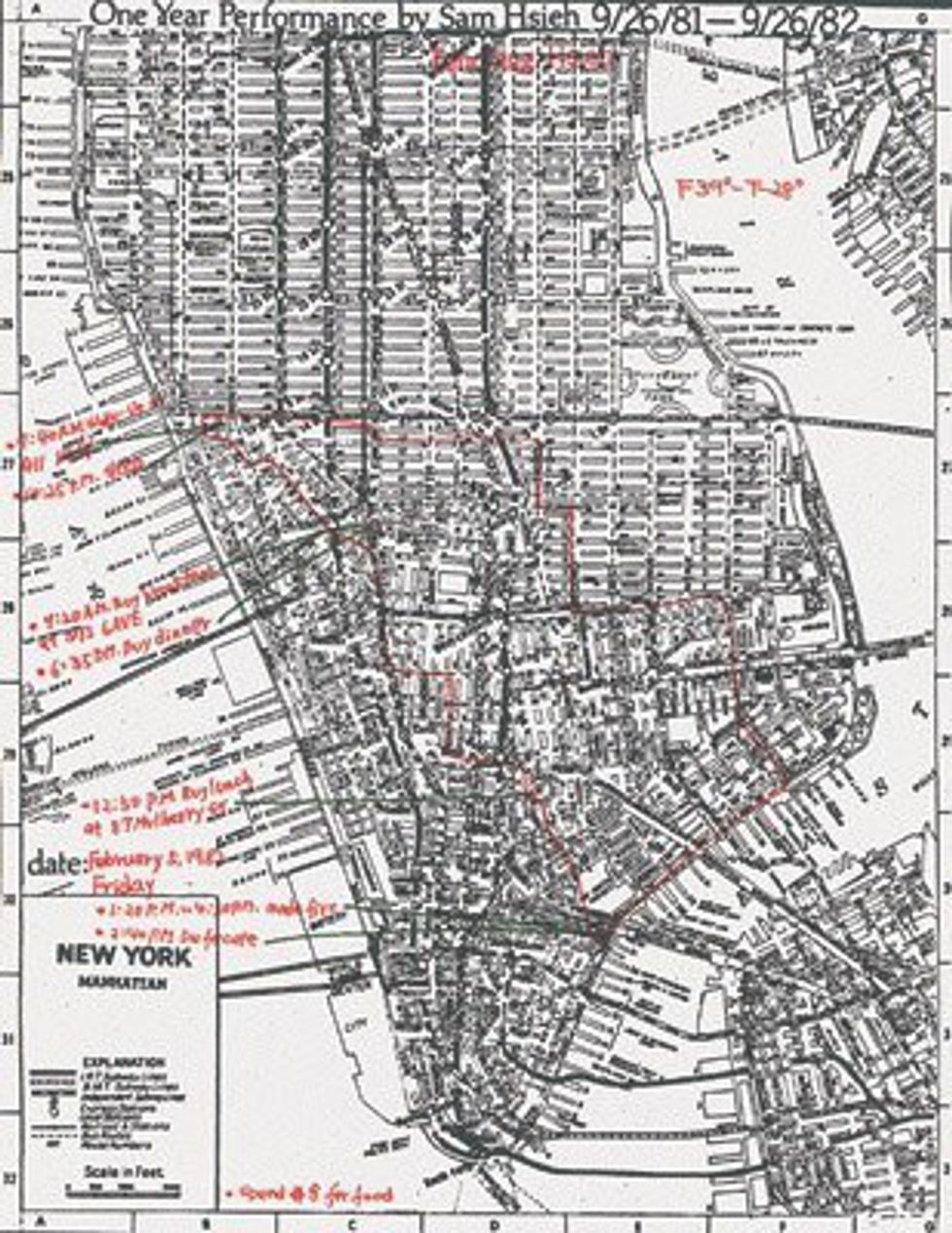

Throughout this period, he kept meticulous daily maps of his movements around the city, tracking what he was doing, where, and at what time. Already, this bureaucratic sort of documentation complicates a piece that seems intended to cast light on the way movement throughout the urban landscape differs when it is navigated “naturally,” functioning as not only the public sphere, but also the private.

Many questions seem to be addressed, such as how do interactions with the cityscape change? And where is the space for private within the public? While these questions arise as a way for Hsieh to contrast experiences of the urban space and the way time is experienced there by fully inhabiting it, they also apply to the homeless population, which is often not contemplated by the public, invisible despite their constant exposure to the public. Thus, his scientific tracking of his supposedly “organic” movement throughout the city becomes further fraught, as his movements, like those of the homeless he lived amongst, are just as based on productivity as those who have private repose in between their public journeys. He has time to wander aimlessly, but he stills makes movements towards places where he can bath, eat, defecate, etc . And with this, his attempt to access a sort of alternate reality of the urban space and its understanding as a site of accelerated living becomes impossible. Instead, he simply adopts the life of an “other,” one who does not have a choice in their eternal situating in the public sphere, but navigate it for the same reasons, and in similar ways as those who do. Like this, Hsieh just becomes another homeless individual on the street, failing to heighten their visibility (especially in regards to the social solitude amongst many they experience, which seems to crop up some obvious questions to be explored), and simultaneously failing to differentiate its conceptions of time and movement from the structures he aims to critique.

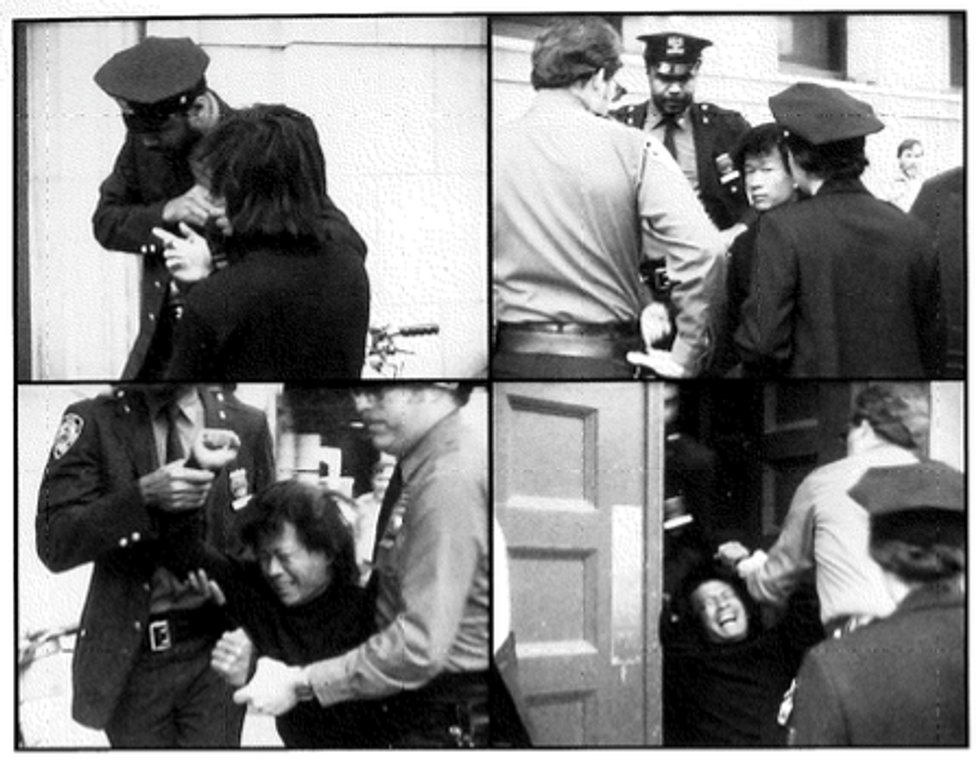

This notion is only heightened when it is considered that much of the struggle of homelessness was removed for him, with a network of individuals to support him financially (and artistically) throughout, ensuring him necessities, such as food . Additionally, his hegemonic success is most clearly seen in the courts’ reactions to his work. He only spent fifteen hours under shelter during this entire work, which was forced when he was arrested for an altercation with another man on the street.

However, on both of the court dates he had to attend, judges had ruled he could remain outside of the building in order to maintain the integrity of his art . In essence, he had worked so rigidly within the framework of institutions in this piece that the institutions complicit in creating the structured context for the work were supportive of its endeavor.

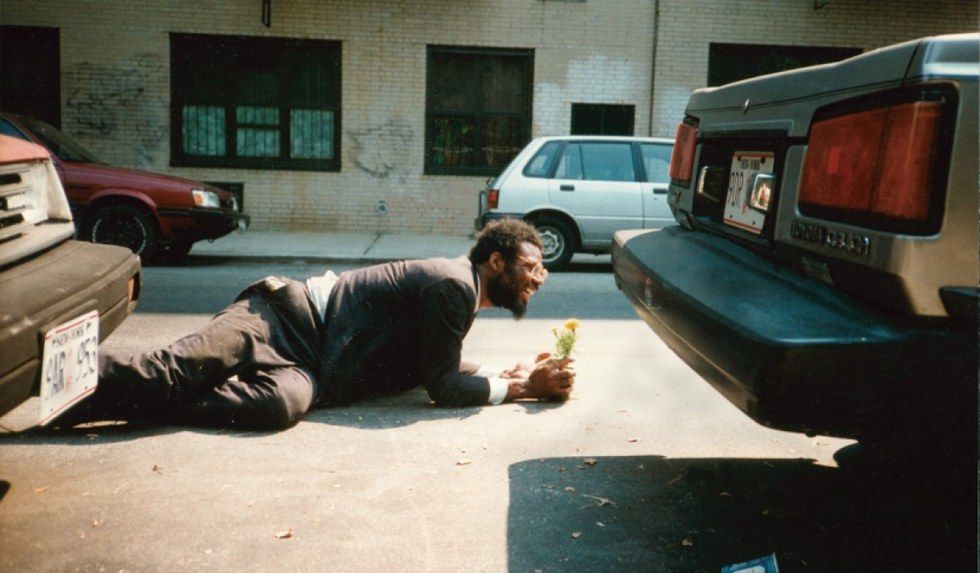

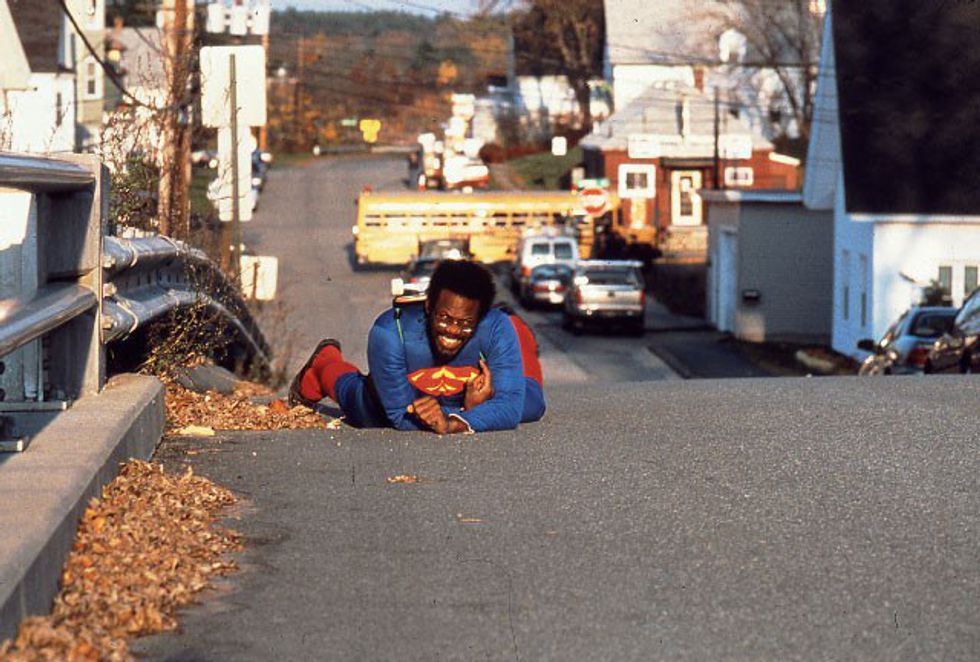

Pope.L, on the other hand, started his crawl series with the intention of seeking to complicate the understanding and visibility of the homeless, as he had first-hand experience with the issue, having various family members who had to live on the street. The first iteration of the crawl was a work called Tompkins Square Crawl, where Pope.L donned a suit and held a single orange carnation in his hand as he slowly crawled along the city streets of New York.

During this performance, though, an onlooker in the community brought the entire performance to a halt when he stopped Pope.L in order to question his intentions—most specifically Pope.L’s positioning himself, a black man, in a demeaning action with a white man following him and taking video of the spectacle (for documentation purposes). Whilst this point is important for discussing Pope.L’s works (like The Great White Way—see below) in regards to his dialogues around the black subject and body politics specifically, I will put it aside for the sake of a relatively succinct comparison.

While the hypervisibility created by this sort of spectacle created a strong adverse reaction that seems to be the point of Pope.L’s work: to provoke real dialogue amongst the public around issues of the marginalized within the very communities such complacency of viewing takes place—an approach that differs vastly from Hsieh’s venturing in the public space in order to change his own relation to it.

Immediately the question of visibility arises, especially when in comparison to Hsieh who, by becoming a homeless individual, simply faded into anonymity along with other people in the same circumstances. Pope.L, on the other hand, creates a sort of visual spectacle around not only the suffering of the homeless subject but intersects it with the suffering of the black community, and possibly even the group where that intersection plays out: homeless minorities. In a discussion around the artist using their body to create otherness, author Emily A. Kuhlmann describes the work in line with these ideas in her article "The Artist's Body as a Site of an Other's Otherness": “Physically engaging the audience by dragging himself across the pavement, Pope.L brings new light to existing social inequalities, without either mimicking the experience of or claiming identification with the homeless population.” Pope.L creates a work that has more of an intervention in others’ daily lives, rather than his own, unlike Hsieh who focused on impacts upon himself an individual and an artist. This approach is not only more apt for addressing a social issue; its confrontational nature also forces viewers out of complacency. And in this case, provoked real conversation and even action on the part of the viewers—the passerby who was offended by the piece eventually got the police involved and the entire performance was halted. Pope.L also refuses to figure the suffering subject as abject by bringing in class connotations with his wearing of suit (in order to combat assumptions about the homeless) and holding a flower (I would argue, in order to combat assumptions surrounding black males), which brings more topics of dialogue to the forefront.

With all of this in mind, I would take one last look at the pieces' shortcomings and successes through the lens of their endurance component as this is where, it seems, that much of the difference of the work arises from. Hsieh and Pope.L take generally different approaches to their understanding of endurance: Hsieh takes it on in a durational way (although there is hardship involved in his living on the streets it would be a stretch to call it “suffering”) while Pope.L must endure through physical suffering in order to craft a sort of activism around physical and emotional suffering in daily life. These differing approaches place the artists amongst varying dialogues, with Hsieh situating himself more amongst the intellectuals who can grasp larger theoretical concepts in regards to theories of the everyday, while Pope.L crafts a dialogue for the common person, catching their eye and forcing them to confront possibly unhappy truths together. From here, it becomes clear who exactly they are providing a voice for: Hsieh the experience of an individual artist, casting him into invisibility amongst others, and Pope.L the subjugation of masses, casting other into visibility. With this, Hsieh’s appropriation of homelessness is not really about homeless individuals, which is why it fails both in its original institution-questioning intentions as well as crafting a potential dialogue about the people he usurps. Pope.L, though, succeeds, as he sets out to address the public from the start and thus, utilizes interventionist tactics to create immediacy regarding the issue, stemming real dialogue and contemplation, rather than elitist intellectual brooding.