The archetype of the femme fatale respectively plays a crucial part in the films The Maltese Falcon (1941), Chinatown (1974), and Brick (2005). In The Maltese Falcon, Brigid O’Shaughnessy is the classic prototypical character of the femme fatale. In both of the neo-noirs Chinatown and Brick, this role has been reinterpreted based on their respective historical contexts. Chinatown’s femme fatale Evelyn Mulwray was reframed by the second wave of feminism, which had massive wins for women’s rights in the years leading up to the movie’s release in 1974. In the years leading up to the release of Brick, there were a lot of changes being made to laws that involved sex-based discrimination. This reframed Brick’s femme fatale Laura.

The Maltese Falcon was made during the fight for birth contraception, and the education of birth control. This was a result largely from the founding of the group The American Birth Control League in 1921 just eight years before the novel, which the film was adapted from, was originally copyrighted. This group would later become Planned Parenthood in 1942, the year after the release of the film. Since the screenplay for The Maltese Falcon was a direct adaption of the novel, it is hard to pinpoint an exact event in women’s history that sparked the character of Brigid O’Shaughnessy. However, since the most prominent social issue of the time of the novel and the film was women’s health and birth control, it is safe to say that it had some influence in the creation of the femme fatale prototype.

Margaret Sanger created The American Birth Control League in 1921, and then the first legal birth control clinic in the United States in 1923 called The Clinical Research Bureau. The goal of both organizations was “to offer an ambitious program of education, legislative reform, and research” on birth control and family planning for married couples and women. As expected, this caused a lot of public upset. Sanger was arrested in several cities while she was promoting her cause. Along with public upset, this also attracted a lot of attention and support for Sanger’s cause.

Among all of the controversy around birth control at the time, this also meant a little more independence for women. Although Margaret Sanger’s whole mission was to educate and distribute contemporary birth control, which was the diaphragm, to couples and married women, it still took some of the biological pressure and responsibility that all women carry.

This new prototype that Dashiell Hammett created in the novel The Maltese Falcon, was a new independent kind of women. Brigid O’Shaughnessy had her own story, her own agenda, and she was not the typical damsel in distress that was very common for the time. Hammett’s novel was released in 1930, just nine years after the American Birth Control League was first created. Since the 1941 film was a direct adaptation, it is safe to assume that all this uproar and controversy around Women’s Rights and independence had some influence on the femme fatale prototype.

The resurrection of feminist activism in the 1960s, 1970s and through the 1980s is known as Second Wave Feminism or The Women’s Liberation Movement. It is widely agreed that this period of time is the most impactful wave of feminism in the United States to date. The second wave of feminism includes but is not limited to, the establishment of The National Organization for Women, the Equal Rights Amendment being passed, ruling unmarried women the right to use birth contraceptives pills, and the creation of Title IX of the Education Amendments in 1972. Then in 1973 the Supreme Court giving women the right to a legal and safe abortion, which overrode anti-abortion laws across America. All of these victories for women, along with many others lead up to Chinatown’s release in 1974. The second wave continued through the 1980s with notable events such as the passing of the first law against marital rape in 1976 and the creation of the Pregnancy Discrimination Act in 1978.

In the 1960s and the 1970s, while feminism was back in full swing, Hollywood had moved on from the phase of film noir. It is considered by film critics that the last true film noir was Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil in 1958. All though the true film noirs were said to be over, Hollywood had adopted themes of noir. In the early 1970s, America was experiencing political and social issues that mirrored the cynical, satirical edge of film noir. Thus began the cycle of neo-noir films. Technically anything after 1958 that has these noir themes and aspects is considered to be a neo-noir. These films not only gave acknowledgment the classic noir, but also rose to popularity in the 1970s and the cycle continues currently.

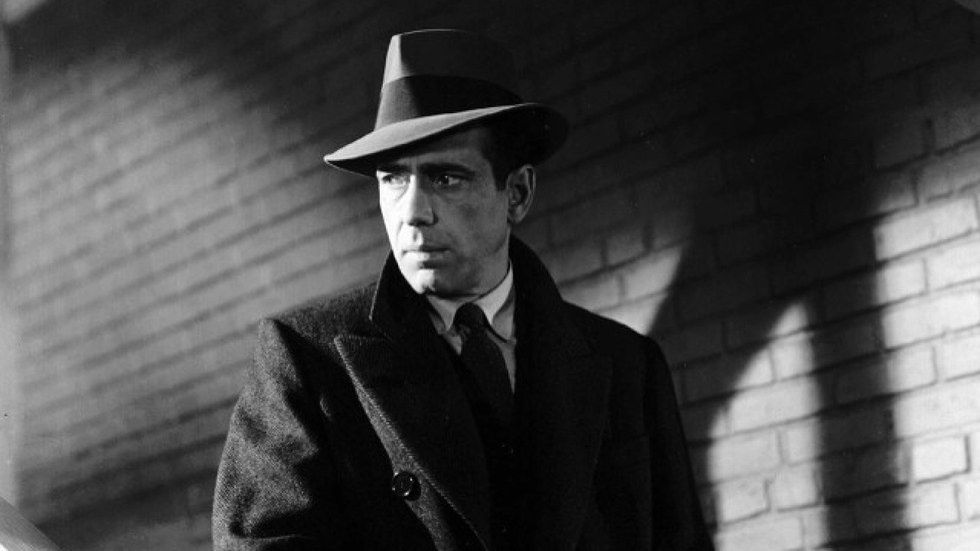

One of the most appraised films of the 1970s was Chinatown, winning the Academy Awards in 1975 for Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay, Best Actor, Best Cinematography, Best Director and Faye Dunaway for Best Actress as the archetypal femme fatale Evelyn Mulwray. Chinatown could have easily been a classic film noir had it been made twenty years earlier. The screenwriter, Robert Towne, was clearly inspired by the film noir classics, including but not limited to The Maltese Falcon. This can be seen through most aspects of the film but especially through the comparison of the character of Evelyn Mulwray to the character of Brigid O’Shaughnessy.

When examining the relationship between Chinatown’s protagonist JJ ‘Jake’ Gittes and the femme fatale Evelyn Mulwray to the relationship between Sam Spade and Brigid O’Shaughnessy, it is clear that Chinatown had reimagined the prototypical femme fatale from The Maltese Falcon. In The Maltese Falcon, Brigid O’Shaughnessy has a messy background story going on, however, it remains a mystery to the audience throughout the film. This is clarified to the audience in the scene when Sam Spade visits Brigid O’Shaughnessy the day after Miles and Thursby are murdered. Brigid admits that her name is not either of the fake names she has given out, and clues Sam in on her involvement with the hunt for the statue of the bird. Even though she has claimed, to tell the truth here, the audience cannot commit to trusting her character at this point because Sam has already declared that he knew she was lying from the start. The distrust from the audience is purposeful and rewarded at the end of the movie when it is revealed that she was the one who murdered Miles Archer after all. However, the audience does not get much of an explanation besides that she got “too caught up in it,” leaving the audience to think of her as a liar, a murderer, and an unsympathetic character, unlike Evelyn Mulwray’s character.

The relationship between Evelyn Mulwray and JJ Gittes in Chinatown is a very close remodeling of the prototype film noir relationship between the protagonist and femme fatale. Even more closely adapted from The Maltese Falcon, though, is the femme fatale, reshaped and reframed by the Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. The audience is suspicious of the circumstances surrounding Evelyn Mulwray and her husband from the beginning, however, the basic fact alone that the audience gets Evelyn Mulwray’s background story, unlike Brigid O’Shaughnessy, is evidence that Robert Towne was influenced by current events while writing her character.

In fact, the structure of the story of Chinatown is not only dependent but also driven by Evelyn Mulwray’s character. The same argument could be made about Brigid O’Shaughnessy and The Maltese Falcon, however, Brigid is painted as merely a catalyst which leaves little to be sympathetic with. Brigid does not stand a chance juxtaposed with the deep examination of the struggles of being a woman that Chinatown practices through the lens of the femme fatale, Evelyn.

The importance of the femme fatale in Chinatown was a consequence of Second Wave Feminism as a whole, however, there is one theme from the movement that is strongly present in Evelyn Mulwray’s storyline and that is rape culture. This is one of the main issues many people immediately jump to when thinking of feminism and women’s rights in general. It was a mainstream fight of the Women’s Liberation Movement and continues to be today. At the beginning of the film, the storyline is seemingly about the mysterious circumstances around Hollis Mulwray’s murder. By the end of the film, it is clear that the movie is truly about the theme of escaping the past, which neither JJ Gittes nor Evelyn Mulwray can do.

Hollis Mulwray’s murder is merely the setup for the real story. Gittes and the audience discover by the end of the film that Noah Cross, who is Evelyn’s father, murdered Hollis over their rivalry and business deals of the Los Angeles water supply during a long drought. By the time the film is past it’s inciting incident, though, the audience has assumed that the original disagreement between Noah Cross and Hollis Mulwray was over Hollis marrying Cross’ daughter Evelyn. By the end of the film, however, we learn that this ‘disagreement’ that tore the business partners apart was actually because Cross had raped Evelyn when she was a teenager and she got pregnant. Hollis Mulwray took Evelyn away and married her to protect her from her father when he found out. Rape culture became widely known during the time of Women’s Liberation in the years leading up to Chinatown’s release.

When Evelyn finally admits that Hollis’ girlfriend Katherine is actually her daughter and also her sister in a very visceral scene at Katherine’s secret home, Gittes asks “Did he rape you?” referring to Noah Cross and Evelyn replies a somber “no”. To the naked eye, Evelyn’s answer is simple. However, this answer itself is a subtle comment on rape culture. According to a study from the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), 68% of sexual assault crimes go unreported to the police, and a large amount of those unreported assaults are incest. With the progression of sexual assault awareness between 1974 and 2016 taken into account, it is safe to assume that this percentage of unreported assaults was much higher at the time of the film. In the end of the film, Evelyn’s need to escape her past is what causes her defeat, and her death. Her father, Noah Cross, the assaulter wins, in the end, making the past that Evelyn is unable to escape a large comment on women’s rights.

The hot topic of feminism and women’s rights in the years leading up to the release of the film Brick was sex-based discrimination and sexual harassment and all of the awful things that includes. In 1999, the Supreme Court ruled that women could sue for sex discrimination if the anti-discrimination law has been violated with as little as indifference to the law. This was the government finally acknowledging what women are still fighting for today, that sex and gender discrimination is not black and white. In 2005 the Supreme Court adds to Title IX, by prohibiting the discipline of someone complaining about sex-based discrimination, the same year that Brick was released.

During the first viewing of Brick through a feminist lens, the film almost seems like a digression in the way that women are portrayed in the film. After more careful examination, though, the lack of faith incompetence and depth that the protagonist Brendan Frye has in women is actually an examination of sex-based discrimination. The film’s story is set in place by the disappearance and then murder of Brendan’s ex-girlfriend Emily Kostich. All though Emily’s character is a damsel in distress, Brendan is naïve to her depth as a consequence of him pining after her and seemingly a superiority complex towards women and everyone else. Brendan’s innocence and superiority towards Emily’s world are what gets him tangled up in the dangerous and twisted storyline that is Brick.

When the femme fatale of Brick, Laura enters the film, Brendan is sure he can use her as a pawn by using her as his ticket into Emily’s world, for information on Emily’s whereabouts and later, her killer. Laura is a closer adaptation of Brigid O’Shaughnessy’s prototype than Evelyn Mulwray. The audience is not given much information on Laura’s own story besides that she was popular, used that as a front for her use of heroin and involvement in the underground drug world and that she had befriended Emily before her disappearance. Brendan does not give the possibility that Laura had something to do with Emily’s disappearance much thought at all. Not until the scene after Brendan and Laura have had sex at Tug’s house; he sees her cigarette in the ashtray and it has the same arrow on the filter as the cigarette that was flicked out of the car that drove by him when Emily had first called him for help does he realize that he has been manipulated at all. Brendan’s ignorance of what women are capable of is not lifted until he is given hard evidence.

By the end of the film, Brendan’s superiority complex towards women is the cause of his defeat. All though he has figured out Emily’s murder, he has still lost in the battle. After Brendan confronts Laura, she reveals to him that Emily was actually pregnant with his baby, not Tug’s. Brendan is left on the football field emotionally alone as a consequence to his own fucked up view of women’s capabilities.

Hollywood has been subconsciously commenting on women’s rights since the beginning of the film. Film noir was when it began to be clear that Hollywood was going to capitalize on women’s rights through the creation of the prototype of the femme fatale, Brigid O’Shaughnessy. In the neo-noirs Chinatown and Brick, this prototype has been reframed by the historical context in the form of the archetypal characters Evelyn Mulwray and Laura. Since The Maltese Falcon, film noirs and neo-noirs have continued and will continue to use this prototype to capitalize on feminism, women’s rights and rape culture.