When the American Revolution is taught in schools throughout the United States, the idea that the American colonists were right and the British were wrong is ingrained in our minds. Besides, had the colonies not protested and revolted against the rule of Great Britain, the United States would not be the same country as it is today. In a country obsessed with patriotism, this notion that the colonists were the good guys and the British were the bad guys is fitting, but also naive. One instance, in which the British Parliament was in the right, but the colonists protested, was the Stamp Act of 1765.

Following the Seven Years' War, or French and Indian War , British debt had doubled. Led by William Pitt, the British government came close to bankruptcy in order to wage one of the first global wars. During the war, the British deployed 30,000 British regulars to help defend its colonies' borders and destroy New France. When the war was over, Parliament decided to leave 10,000 soldiers in the colonies. Since 70% of Britain's budget was spent dealing with debt, they needed another way to pay for the troops. The British Prime Minister, George Grenville , decided the best way to increase revenue was to tax the colonies. At the time, colonists paid five times less taxes than those in Great Britain. Grenville first passed the Sugar Act in 1764, which lowered the tax established by the Molasses Act in 1733, but increased the enforcement and collection. Taxes from the Molasses Act were never collected, due to colonial evasion. Although there were complaints towards the Sugar Act, it was mostly with the merchants whose jobs became more difficult. However, the Massachusetts Assembly believed that the Sugar Act was unconstitutional, because it was an act pertaining to revenue and not trade. They believed Parliament could only enforce trade, but could not tax the colonies. Widespread protest would not occur until Grenville decided to pass the Stamp Act the following year.

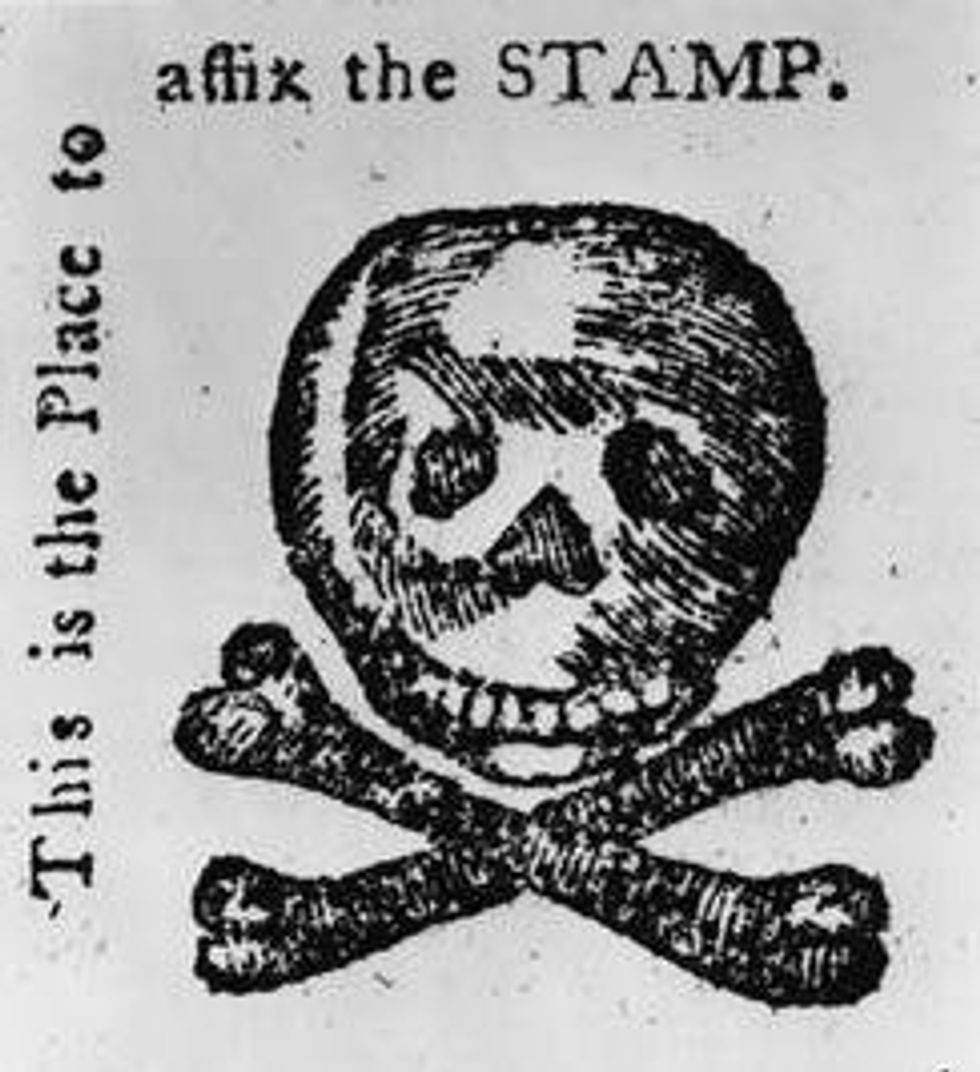

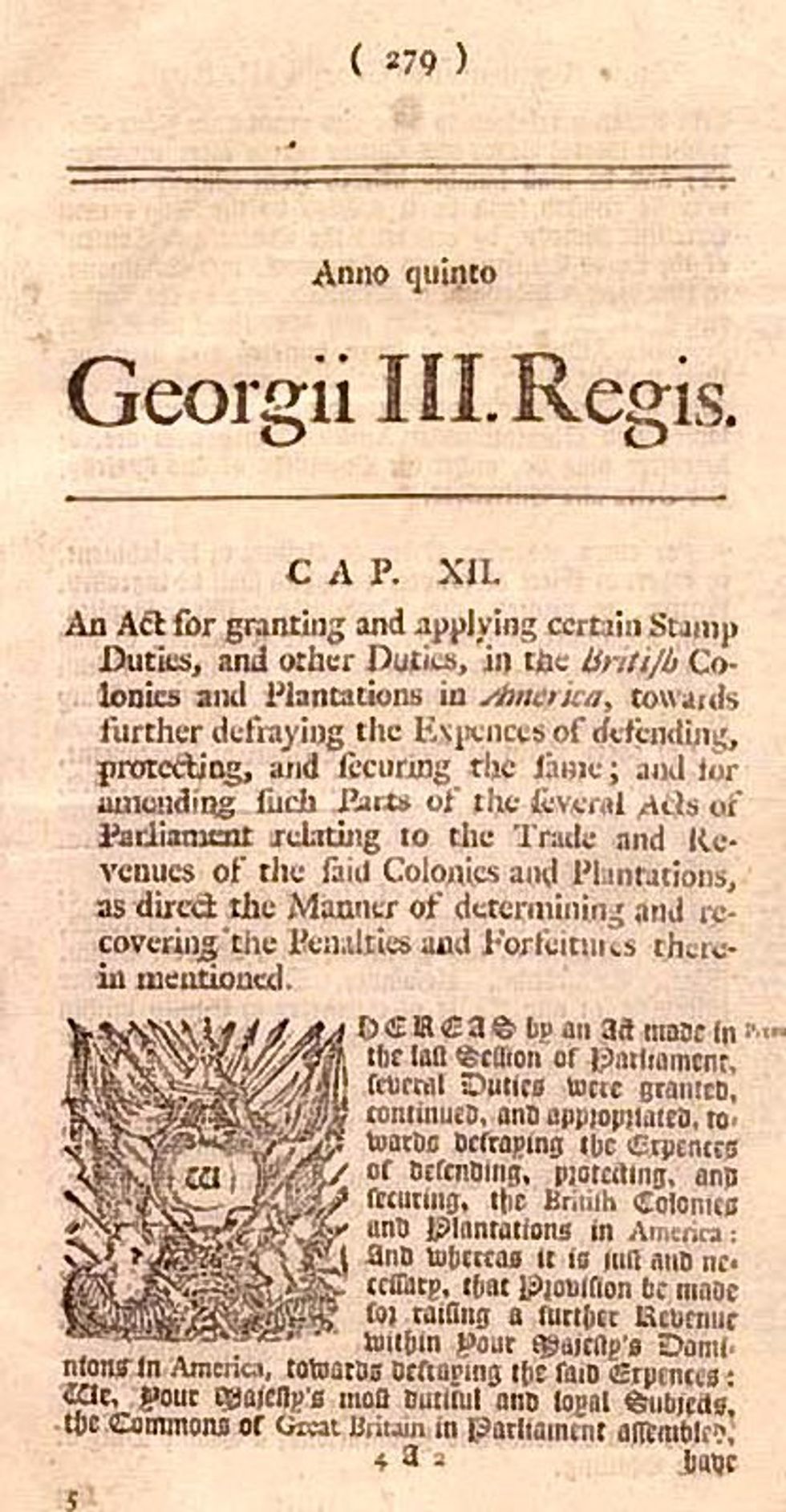

In 1765, Grenville decided to pass the Stamp Act which directly taxed the colonies. Although the name implies a tax on postage, the Act pertained to all printed materials. Printed materials, such as legal documents, playing cards, and bills of lading, had to be fixed with a royal stamp. Unlike the Sugar Act, which mostly effected the merchant class, the Stamp Act effected everyone. When Grenville passed the Act, he expected opposition, but not to the extent in which it came. In England, there was already a Stamp Act, and it was not met with controversy, so it is unlikely that Grenville believed the Act would bring up a larger issue.

In the opinion of historians Edmund and Helen Morgan, Grenville's intentions with the passage of the Stamp Act was not only to increase revenue, but also to assert Parliamentary supremacy. This argument stems from the method in which Grenville passed the tax. Grenville originally gave the colonies a set amount of time in which they could tax themselves, but did not provide specifics on the amount. He also did not go through the proper channels in informing the colonists of the tax. However, if Grenville already believed in Parliamentary supremacy, it can be assumed that he didn't think he needed to make any special accommodations towards the colonies; Parliament's word was law. It can also be assumed that the assertion of Parliamentary supremacy was involved by looking at the grievances of the colonists. In the Virginia Stamp Act Resolves and The Stamp Act Congress, the chief complaint is that Parliament did not have the right to tax the colonies, only colonial assemblies could. Although the colonists are arguing against Parliamentary supremacy, their reasoning was flawed.

Ben Franklin and Patrick Henry, leaders in the opposition against the Stamp Act, had differing theories on taxation from Parliament. In an interview with the House of Commons, Ben Franklin differentiates between internal and external taxes. External taxes, according to Franklin, were taxes placed by Parliament on luxury items that were imported into the colonies from Britain. Franklin believed that Parliament had the right to lay external taxes, because if the colonists did not like the price of the commodity, they could refuse to buy. Internal taxes, on the other hand, which Franklin believed the Stamp Act was, were taxes on necessities already within the colonies, and could not be avoided. Since they could not be avoided, Franklin believed internal taxes could not be enacted by Parliament unless the colonists had representation. The interviewer then brings up an interesting point to Franklin; what if Parliament taxed necessities that were imported? Would that be considered an internal or external tax. Franklin responded by saying there wasn't a necessity that he was aware of that couldn't be produced in the colonies. This, of course, was false. All manufactured goods had to be imported from Britain, so a lot of manufactured necessities, at the time, could not be produced in the colonies.

Unlike Franklin, Parliament did not see a difference between external and internal taxes. This differentiation suggest that the colonies do not fall within the British Empire, which was simply not the case. A taxed passed by Parliament was a taxed that had to be paid; it did not matter if it was on luxuries or necessities.

Patrick Henry, mastermind behind the Virginia Stamp Act Resolves, argued that the rights of the colonists as British subjects was being infringed upon by the Stamp Act. The charters of the colonies, which were granted by the king, guaranteed the rights of natural born British citizens to the citizens of the colonies. Henry believed that taxing the colonists, without representation in Parliament, went against their rights as British subjects, and therefore, was unconstitutional. He believed only the colonial assemblies, which were elected by the people could pass such taxes.

Parliament had a different idea. Parliament believed that although the colonists were not able to vote for members of Parliament, they were still represented in Parliament. Unlike in the United States today, where Congressmen represent the interest of their constituency, British Parliament members represented the British Empire. Members of Parliament were not elected to serve the best interests of their district, but rather the best interest of the whole empire, including the colonies. This idea is now known as virtual representation. Another argument of Parliament was dealt with Henry's claim that the colonists were guaranteed the rights of natural born British subjects. Although Parliament did not disagree with this idea, they did cite the fact that this notion came from charters which were granted by the king. Charters were not set in stone. Just as easily as they could be granted, they could be revoked. Legislation by Parliament was not this way. Also, if the colonies wanted to claim that they had the rights of natural born British subjects, they also had the same obligations of natural born subjects. All British subjects were bound by legislation passed by Parliament, whether or not your elected assembly was against it. If the colonists wanted to argue that they were British subjects, then they would also be bound to Parliamentary supremacy.

The Stamp Act was repealed in March of 1766. Widespread colonial protest and mob violence led to resignation of every single tax collector in the colonies. The colonial boycotts on the taxed goods were hurting rather than helping increase revenue. The repeal of the Stamp Act was coupled with the passage of the Declaratory Act, which asserted Parliamentary supremacy. Grenville and Parliament did not intend on asserting their power with the Stamp Act, but the actions of the colonists forced them to do so. In the case of the Stamp Act, Parliament had every right to pass the law, but the entitled colonists, who were usually spared from taxes, threw a large temper tantrum, that along with other tantrums, led to the American Revolution.