I hate Valentine's Day. It's true. I always have. Something about giving the object of your affection chalky candy hearts and wilted roses one day a year to absolve yourself from being romantic for the other 364 seems to me like a bit of an excuse. Not to mention those creepy life-sized bears which every couple I knew in high school seemed to magically acquire, and which I shudder at the memory of. (Ugh.)

And yes, there's the trope of the sad, lonely individual crying their eyes out next to a deflated heart-shaped balloon and eating generously from a bucket of ice cream- i.e. me during finals- that we tend to ascribe to someone who dislikes a day that commemorates love. It's in bad form, I guess, to be ambivalent on a day when you're supposed to be really, really happy. After all, Valentine's Day celebrates what is, if we are to believe the Victorians, both the simplest and most painfully complex act of all: falling in love.

But... does it really?

If you, like me, are skeptical of this holiday tradition of romance, then here's a story of bitterness that's sure to sour the words of even the most ardent poet: the "vinegar valentine."

It's a tradition as old as human interaction: say you really, really dislike someone, and you happen to know they dislike you back. But, much like with a crush, you can't come out and confess your feelings, because that would be... embarrassing? Too easy? Potentially lead to you being sued for libel? Any number of things.

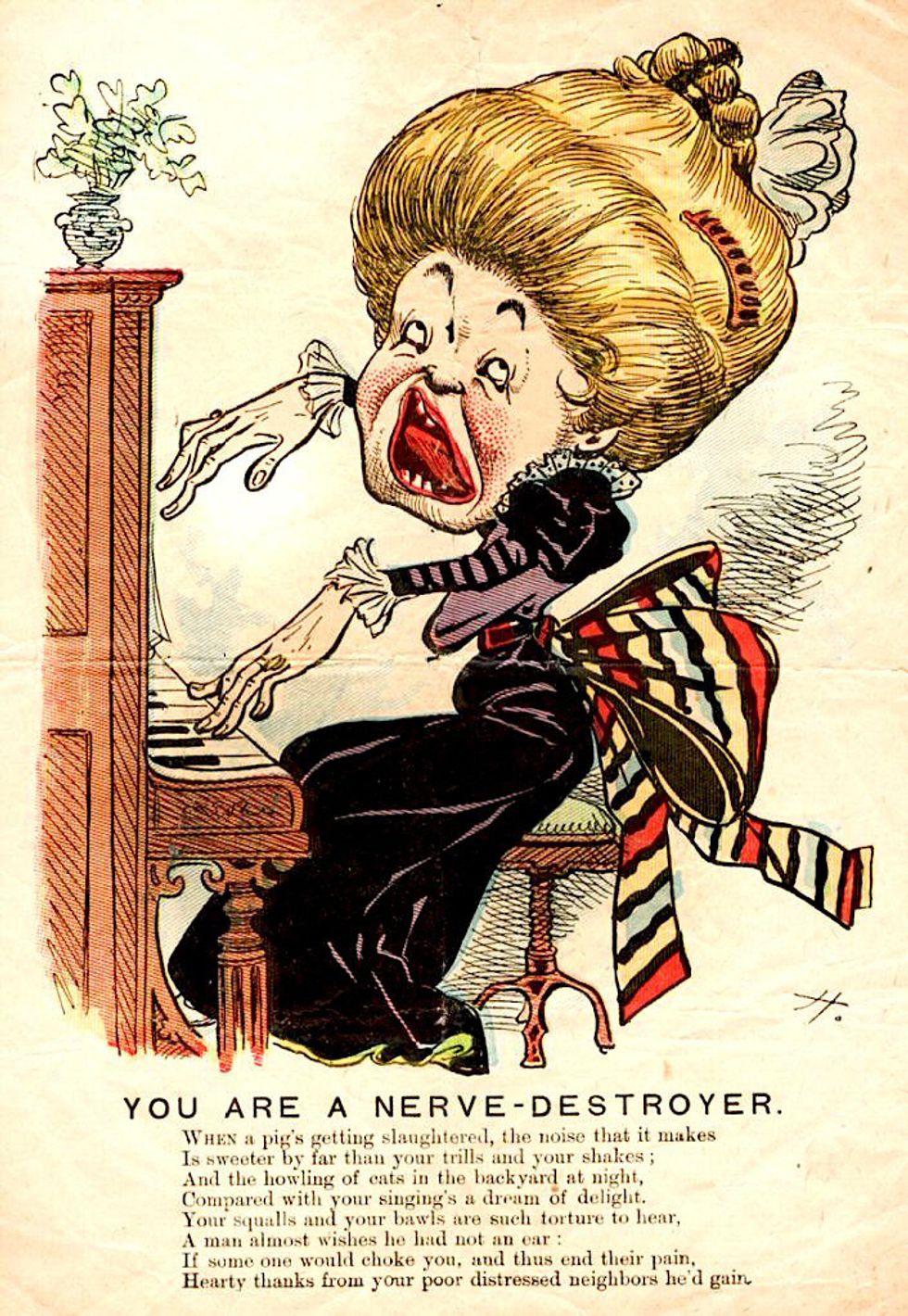

This might seem like an unsolvable conundrum, but never fear: it's the perfect situation for an anti-valentine. This is what, in the 1850s, would have been called a "Vinegar Valentine": a mean-spirited, slightly passive-aggressive note to the object of your disaffection.

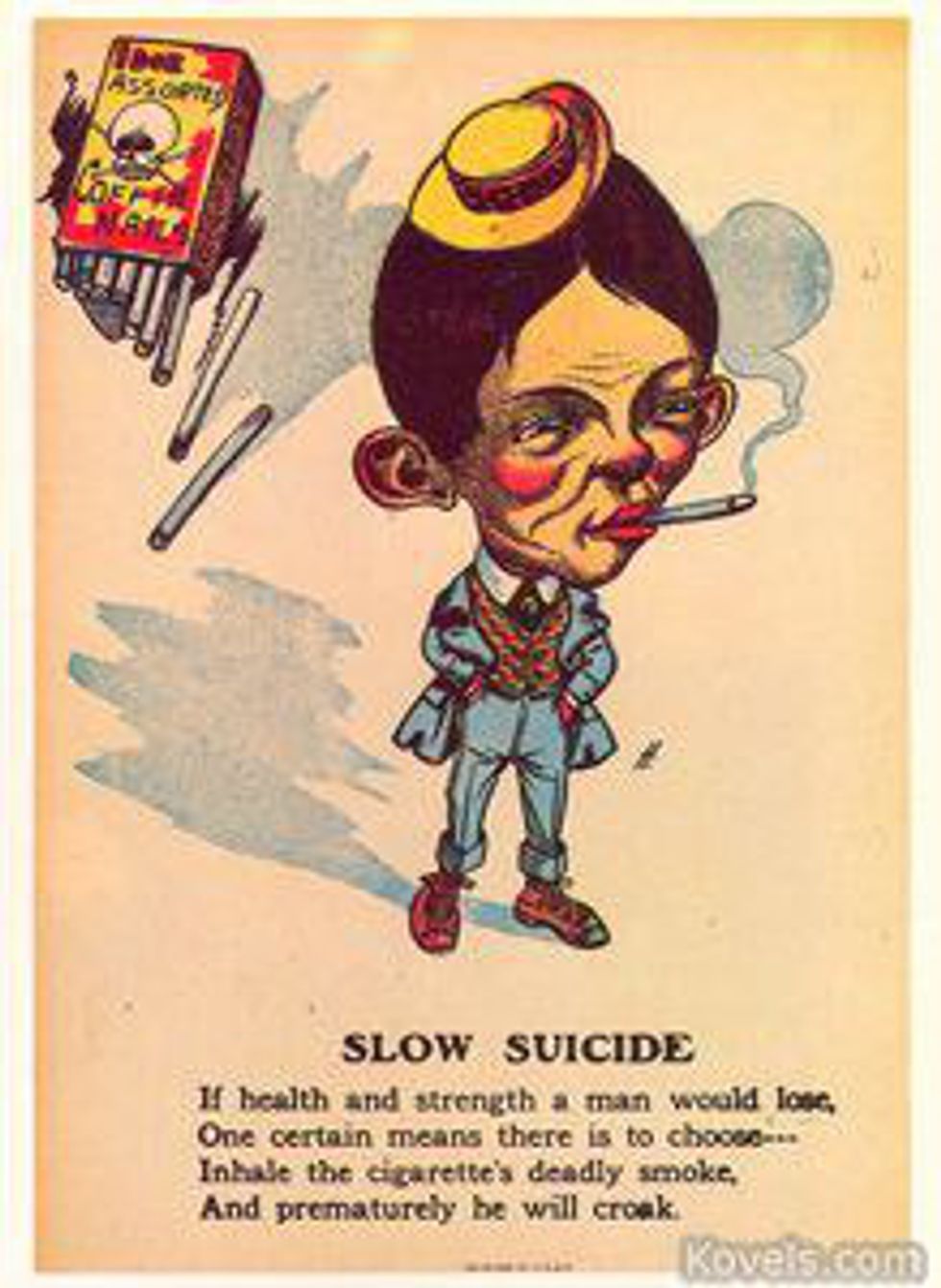

Some of them, as above, are pretty brutal: others take a slightly more joking tone.

And still others reveal that they're only concerned about your health.

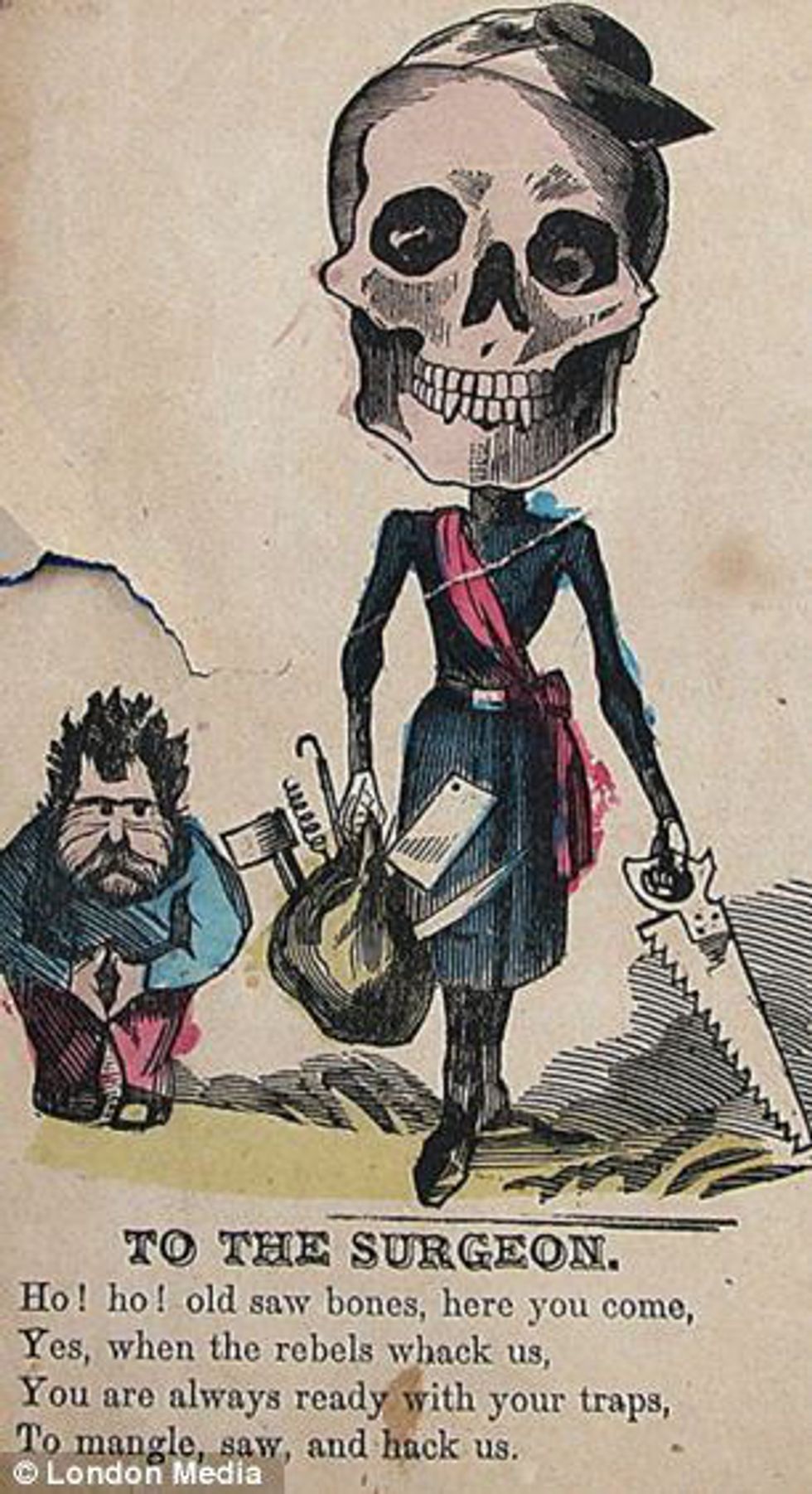

You can make fun of someone's job,

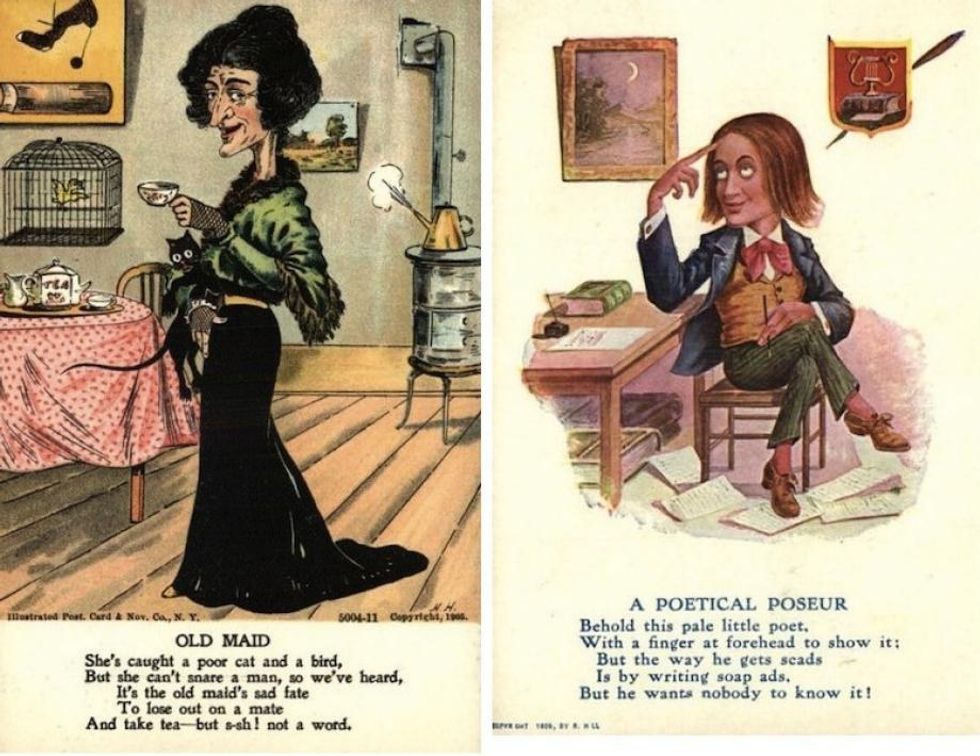

their family,

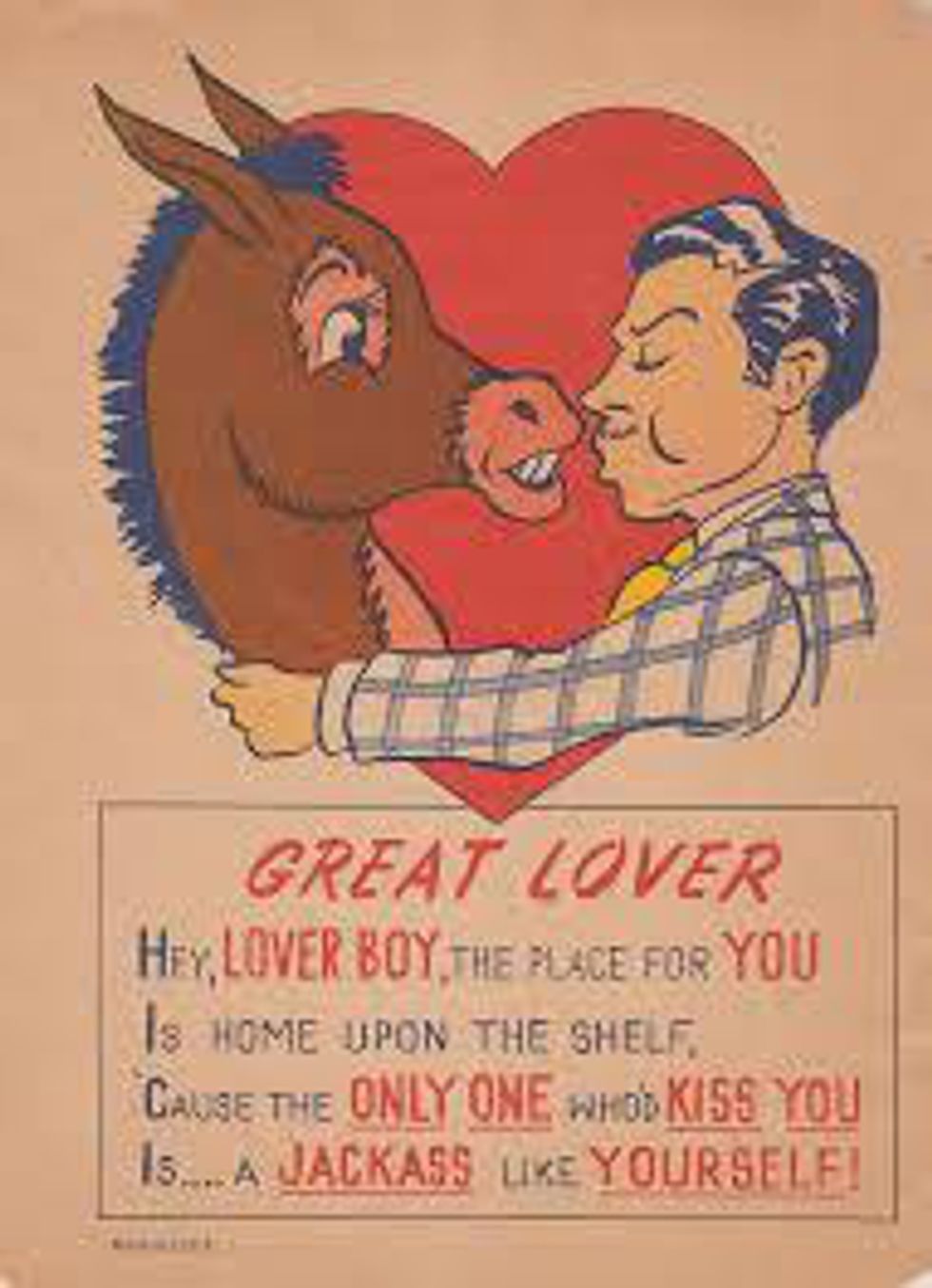

or even, if you've had a bad breakup on February 13th, their capacity as a lover.

They began, in the 1840s, as an anonymous way to send annoyed notes to a friend or co-worker, but they soon became "a socially sanctioned chance to criticize, reject, and insult.. [and] were often sent without a signature, enabling the sender to speak without fear." They were often incredibly elaborate and sometimes made by the same companies that distributed the traditional frilly Valentine's cards. Eventually, in the 20th century, they fell out of style, and nowadays the sense of anonymity they once provided has been replaced by many other sources, not least the Internet. But, if we are to believe the few sources from that time who wrote about giving (and receiving) these tokens, there's just nothing like sending a carefully-selected, hand-crafted card to someone you really, really dislike.

So, the next time you're feeling bad, spiteful, or just mischievous around Valentine's Day (or, let's face it, any day), consider sending someone a vinegar valentine. Who knows: maybe you'll make a new frenemy.