The birth was a success. Her first one. There had been a slight complication with the baby's shoulder in the birthing canal, but they had made it through. Stephanie waited until everyone in the room had gone.

When it was finally just her, her husband Steve, and their new daughter she said, "Get the wrapping paper." Without hesitating Steve brought it over to her in the hospital bed, where she lay holding their flushed, blue-eyed, baby girl.

Stephanie had learned somewhere along the way that you could test a newborn's hearing by crunching the wrapping paper near their ear, that this, in turn, will trigger the baby to wiggle their hands and feet.

She was comforted as little Shannon's tiny arms and legs danced when Stephanie crumpled up the festive paper in her hand. Steve and Steph exchanged looks, thankful that their baby girl had all ten toes, all ten fingers, her father's eyes, and as far as they could tell, the ability to hear.

The chance of passing on deafness from birth is very slim, as it is a recessive trait that causes a genetic mutation. Stephanie had a reason to be nervous though. According to the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, being born deaf happens to about three of every 1,000 babies born in the United States.

Stephanie had happened to be one of them. It would take her parents nearly three years to figure out that something wasn't quite right. Like most hearing babies, Stephanie babbled and cooed, a nonintentional trick by hard of hearing babies, which is often why hearing issues are not discovered until the talking stage of childhood.

She played with her siblings and learned to do as they do, but her voice (or lack of) was what would set her apart from her sister and brother.

In the summer of 1969, Stephanie and her family piled into their green station wagon and went on a road trip to visit family in the state of Washington. Driving from Eastern Iowa, the trip would be a rather long one.

Stephanie's older sister, Debbie, had compiled an album of magazine cutouts and was determined to use that time to teach her how to talk. In the back of their family station wagon, sitting amongst both her grandparents, her brother Chris and sister Debbie, Stephanie soaked in all the attention and watched as Debbie tried to teach her how to form words.

She studied her older sister's face as she exaggerated the movements of her mouth and pointed at the photos as she pronounced simple words in front of Stephanie's gleaming face.

Stephanie had learned by watching her older siblings before, things like opening cabinets and using the bathroom. Yet after hours of trying and no success, Debbie reluctantly accepted this would be something she wouldn't be able to teach her baby sister.

Her parents decided that maybe Stephanie needed to have tubes placed in her ear as her brother had done. The procedure consists of surgically inserting small plastic or metal tubes into the eardrum, which allows drainage of excess fluids and reduces chances of ear infections. When the results of the surgery yielded no change in Stephanie's ability to pick up on speech, it was decided by her doctor that the family take her to the Wendell Johnson Speech and Hearing Clinic in Iowa City.

Within ten minutes of the appointment, less time than it took for her family to drive from their home in Bettendorf to the clinic in Iowa City, the doctor said with assurance that Stephanie was, in fact, hard of hearing. Her sister, Debbie, was heartbroken. Her father sat Debbie down to explain what had gone on at the appointment in Iowa City. "Now that's enough crying. We will do everything we can and she will be just fine." Their father soothed his children's fears as they braced themselves for Stephanie's challenges ahead.

She was given her first hearing aid. With a lunch-box sized device to carry around and a weird contraption to place on her ear, Stephanie's life was drastically changed. Despite the awkwardness of the device, she was willing to do whatever it would take to hear and was overjoyed when the results flowed through her ears.

As time went on technology evolved and her lunch box hearing aid turned into a smaller device she could hang from her neck, under her clothes. The discretion of the newer hearing aid was a bonus.

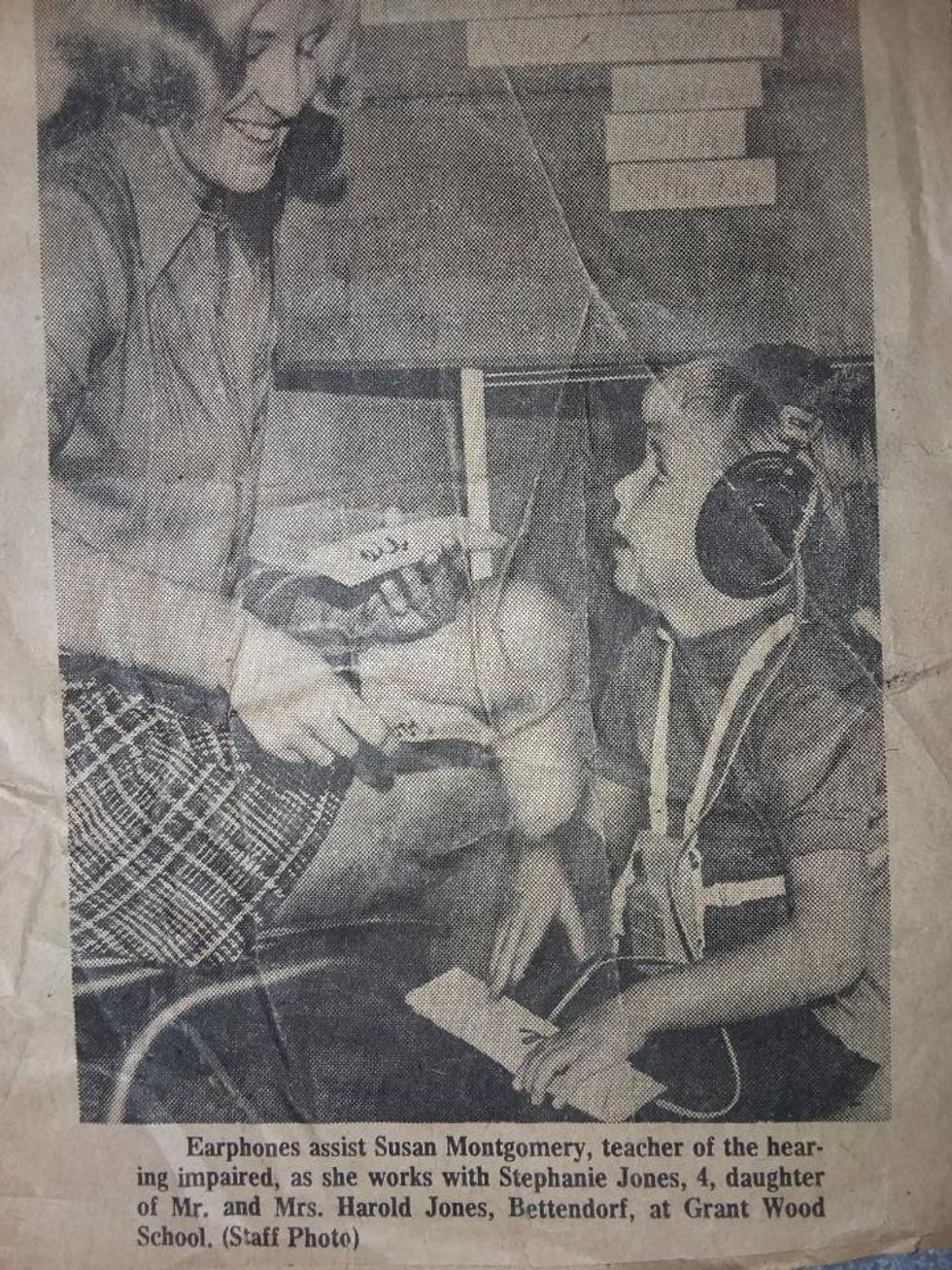

When it came down to the decision for school, Stephanie's parents had two options. Send her to the school who can teach sign language, or send her to the school where they can teach her to talk. The next week following the appointment, at just three years old, she was enrolled in Grant Wood Elementary school, working with her first teacher and speech pathologist, Susan Montgomery. It didn't take long for Stephanie to finally begin talking.

Every day for half a day, Stephanie would go to school, working on physically learning how to pronounce words and letters. While other children learn to speak and enunciate by being able to hear and see how an adult says words, Stephanie would not have the same connection.

"I had to learn what sounds are supposed to sound like," Stephanie says, explaining how her speech is affected by her hearing. She had to learn what exactly one does with their tongue, lips, and jaw for every sound of the alphabet. The letter Z is one of the hardest.

"I still can't do the "Z" sound, it feels so unnatural." Stephanie had to physically learn the different sounds that different combinations of letters create, like words containing c and h together or s and h together. For Stephanie, she hears no difference in the enunciation of the two and to this day has a hard time telling them apart and pronouncing words that contain them.

The family went camping often. With blankets and fishing gear in tow, they would hook up their Starcraft fold-down camper, load up the coolers, and flee into the woods for a weekend away. Stephanie liked to sleep in between her mom and dad during those dark nights in the wilderness. No lights, no sound, Stephanie soothed her childish fears of the night by grazing her hands over her father's face while he slept.

On the fourth of July the family often gathered at Lake Story with friends and family as they celebrated their country's independence. Fireworks were terrifying for Stephanie. While the other children ran around with their sparklers shrieking as the displays exploded into the sky, Stephanie would confide in her father's arms as far away from the commotion as possible, mortified by the all-to-familiar silence that was broken by the loud booms she could feel in her chest.

While almost every child in America woke up on Saturday morning in the 1970s to watch Scooby Doo and The Jetsons, Stephanie raced to her family's television to watch the real-life people acting in Gilligan's Island and The Brady Bunch. Happily reading their lips as the actors flashed across the screen. In animation, a character's mouth typically only opens and closes as they speak.

For most situations, Stephanie relies on reading lips to help her understand what she cannot hear. Watching cartoons where mouths do not actually form words it is harder for her to understand what they are saying. This led her to hate cartoons and anything animation.

Her older brother, Chris, was learning to play guitar. He would call Stephanie down to his room in the basement and encourage her to sing along while he played. To her family's amazement, her voice was perfectly on key. Her love for music grew fonder as her siblings pressed for her education in singing, piano, and clarinet. She may not have been able to hear, but enjoying music was not ruled out.

"I never knew what my limits were. I had always been able to hear the different notes in music. That's my biggest fear; if I lose my hearing later, I'm going to lose music."

Most of the people in Stephanie's life knew that she typically followed along in conversation by reading lips. Socially, she faced some challenges. At young ages, her friends often giggled at her confusion when she had missed wheat someone said. As she got older, there were fewer people who commented, and the ones who did showed just how disgusting society can be by doing so.

Stephanie sat in her desk as the class snickered around her. She was in her high school English class, and the teacher had just made a comment about her. Teasing to the entire class, "I better cover up my lips because Stephanie's going to be able to hear what I say." She had dealt with the kids her age taunting or making comments, but this was an adult figure she was supposed to respect and trust.

Following that class, she went to her speech pathologist down the hall and told her what had happened. She never did receive an apology for the appalling behavior from that teacher, but it never happened again either.

In the fall of 1985, Stephanie moved out of her small hometown for the first time. Three and a half hours away from her family she began life at Northeast Missouri State (now Truman State). As she started to make friends, she often got the question if she was from Boston. She never wore her hair up in a pony-tail, always down over her ears. A subconscious effort out of embarrassment to cover her hearing aids.

These new-found friends had no idea that she was hearing impaired and mistook her slightly different speech for an Eastern accent. It was that September she met Steve at a fraternity party and began dating the love of her life.

"Well, I thought she was from New York." Steve says, laughing softly as they reminisce on dating in college. "It really didn't matter to me a whole lot, we've always been able to communicate very well. I gradually stopped noticing her speech impediment, if you even want to call it that."

Stephanie's hearing has never affected their relationship. In fact, in some ways, it has made their connection stronger. Steve has been and is always there to help her by explaining pronunciation for certain words. "I don't want any grandchildren with the name of Zachary, that is so hard to say." She says as she and Steve laugh together about it.

In 1995, she agreed to participate in surgery to try and fix her hearing. This procedure would be attempting to fix the malleus "hammer" bone connected to the eardrum. The function of this bone is part of the process in transmitting sound and vibrations from eardrum to inner ear. The surgery was successful for a brief period, but her hearing eventually faded away again and she returned to depending on her hearing aids.

As she gets ready for bed now, she prepares for her most relaxing part of the day. Before turning off the bedside lamp and going to sleep, she unhooks the hearing aid from her right ear, switching it to the "off" setting, placing it in the little dish on her nightstand. This is a moment she looks forward to each day. The peaceful liberation of absolute silence. Like the satisfaction of taking your shoes off after a long day, a breath of relief escapes her chest as she is finally able to be relaxed.

This serene silence is a part of Stephanie's life. The silence has never scared her. Wearing a hearing aid every day isn't painful, but it is noticeable. Imagine having an object placed in your ear every day. She could wear it in her sleep, but there would be no reason.

The hearing aid creates an irritating background noise, magnifying every sound around her. Taking the device off, she can finally feel peace in the quietness.

As time goes on, Stephanie has noticed a decrease in what little hearing ability she has. Talking about the process of building a new home together, Steve mentions how there are certain features they will include: emergency lights that flash, as opposed to depending on the beep of a fire alarm; security cameras at the door so if she doesn't hear a knock at the door, she can see when someone is there.

They have spent time researching and has been able to design their new home, optimizing the interior to suit her. "When we were dating," she says looking at Steve, "I used to be able to hear him a little without my hearing aids."

Although she has never been scared of her hearing before, she is fearful of what might go with time. "I never knew anything different. I still don't know anything different. This is how I am. It's not something that I miss, I never really had it."

Do You Secretly Have A B.S. In Sarcasm?