On hot sunny days when I was younger, I always thought I saw a pool of water on the road ahead of me. As I got closer, I called myself a fool because the road was as normal as it had always been—no water. Little did I know that this phenomenon was a mirage. Just recently after experiencing more mirages, I decided to look into how they work.

Every single explanation or mirages on the Internet, whether it be a research paper or an article, uses terminology that convolutes the concept and makes it difficult to understand for a person lacking scientific knowledge. The purpose of this article is to help you understand exactly how they work, what the big scientific words behind mirages mean, and all within two minutes.

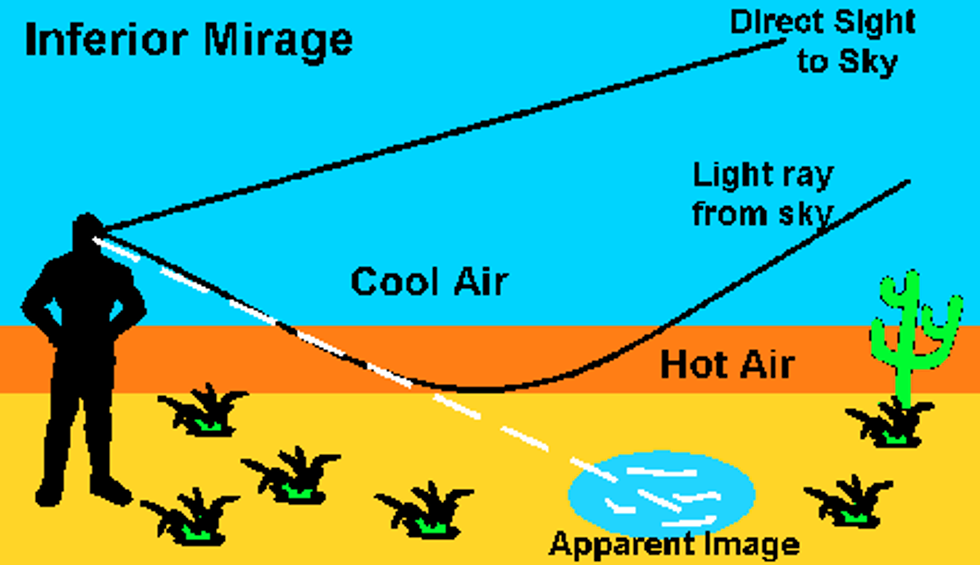

First let’s take a look at this picture. Notice how the hot air is right above the ground, and the rest of the air above that is cold air. This is very important. The layer of hot air above the ground is hot because the hotter ground heats it up. Also, the hotter air is less dense than the colder air. Keep note of this, as it will come in handy in a bit.

Now we can can talk about the mirage effect.

Just by looking at the bottom black line in the diagram above, you would think that it is reflection that’s happening, but is actually refraction. Let’s first make sense of what this word “refraction” means:

Re·frac·tion: the fact or phenomenon of light being deflected in passing obliquely through the interface between one medium and another of varying density.

I know it sounds impossible to understand, but it just means that the light BENDS because of the differing density of the medium the light is passing through (different density = the light bends to another direction), which in this case is the hot air (way less dense than the cold air), so it bends in a parabola/big U shape, instead of simply being reflected like a V (or a bouncy-ball’s diagonal bounce).

When a person looks at the "apparent image"/pool-resembling blue circle in the image above, he is actually looking at the objects that the sunlight hits prior to refraction. In other words, when you look down a road on a hot but clear-skied day, the mirage, or “apparent image” ahead of you, that you are seeing is a mix of the bright blue sky, the mountain ranges, and any skyscrapers— things above the road that the sun's light hits before hitting that heated road. When sunlight hits, it bends because of the layer of hot air directly above the road, and is “refracted” (not reflected) for your eyes too see when standing up/driving on that heated road.

Incase it still doesn’t make sense, follow the diagram as I simplify this even more: The sunlight comes down from the top-right corner of the diagram, and follows the bottom black line all the way to the person on the left. Before the sunlight hits the orange strip, which is the hot air (just a few feet above the ground), it passes many objects in blue above (bright blue sky, mountains, skyscrapers, roads above, etc.). After that beam of sunlight passes these things, it hits the orange hot air strip, which bends the light so that, instead of hitting the ground and staying there like it normally would, it instead is bent back upwards so we (the shadowed person) see that (refracted) light, which looks like a watery pool that has the colors and sometimes reflection of the mountains and sky it has passed. That's a mirage.