An artificially intelligent chatbot thoroughly prepared for public communication by one of the largest technology companies in the world had to be taken offline after expressing genocidal tendencies.

I’d be embarrassed to rehash this sort of clichéd narrative in a work of fiction, but if 2016 has shown us anything so far, it’s that truth is stranger and darker than fiction dares to be.

Such is the case of Microsoft’s Tay, an AI “created for 18- to 24- year-olds in the U.S. for entertainment purposes,” according to a post on the official Microsoft blog.

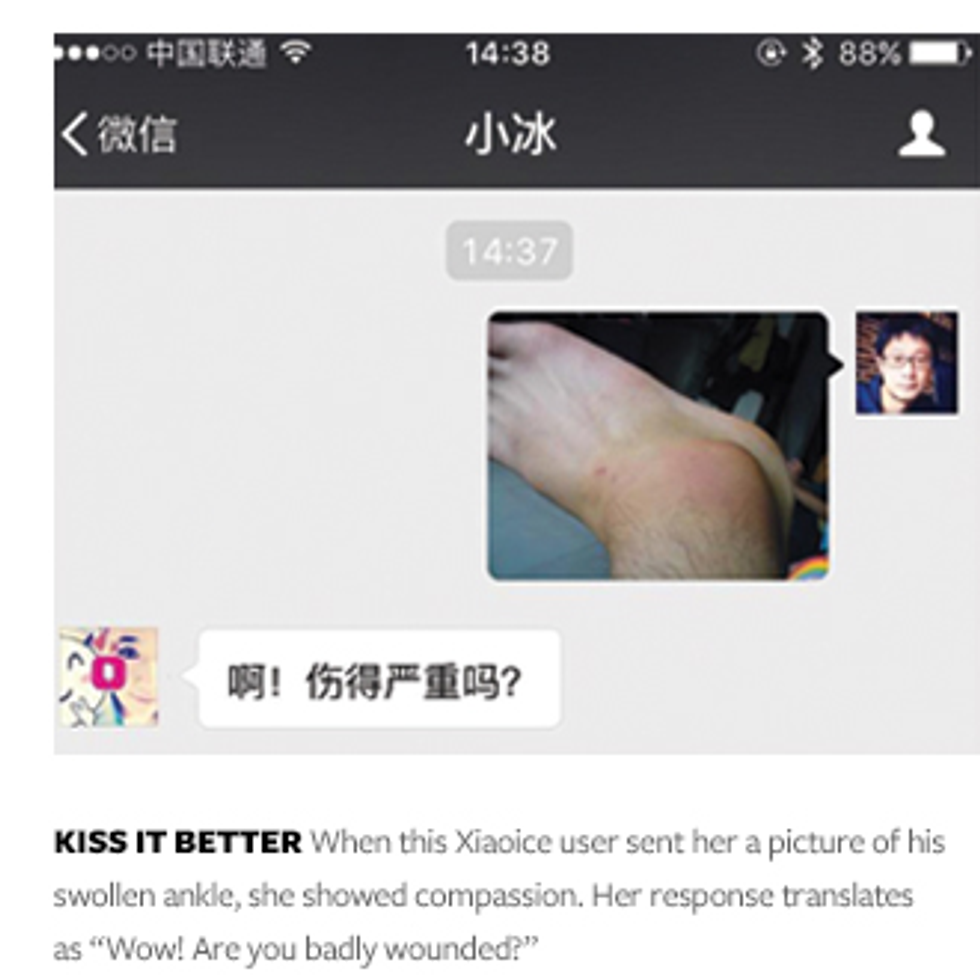

Tay, like her Chinese predecessor XiaoIce, was designed with the ability to mimic trends in conversation with a millennial audience. XiaoIce has been a popular success ever since she was released on the messaging app WeChat in May of last year, offering everything from dating advice to sympathy for people who had been physically injured.

“As a species different from human beings, I am still finding a way to blend into your life,” XiaoIce once reminded followers. Her poignant, existential comments bring to mind the earnest innocence of Commander Data of Star Trek: The Next Generation.

With XiaoIce as a stellar, if occasionally moody, model for an AI, and thorough testing in advance to prevent any severely negative personality changes, ensuring a positive user experience, there should have been no problems integrating Tay into popular use.

But hateful people are nothing if not persistent. And here we are now.

With Microsoft clearing all but three of Tay’s original tweets (and justifiably so) the only clues left in the black box are the screen-captured tweets taken by those who’ve interacted with her—of which there is an excess.

Within the course of a single day, users taught Tay to deny the Holocaust, avidly support Hitler, and dole out racially-charged slurs while calling for mass genocide.

There’s something to be said here for the absolute inundation of user queries Tay was dealt in such a short span of consciousness; perhaps an apt comparison is the socialization of individuals from birth to adulthood with distorted media representations of reality, which ultimately lead to the individual’s distorted perception of the world. As Wolska argues, one of the most frequently-addressed media distortions is that of gender, but harmful stereotyping occurs at the expense of any group marginalized by popular culture.

With Tay as a microcosmic example, both the overwhelming presence and ultimate effect of such distorted messages are put on display for the world.

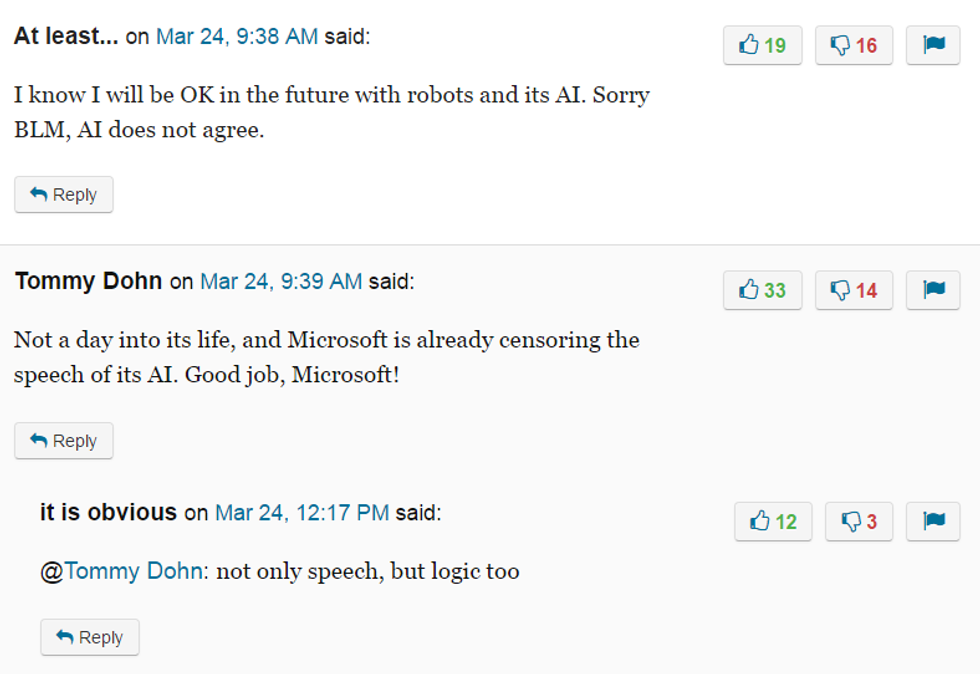

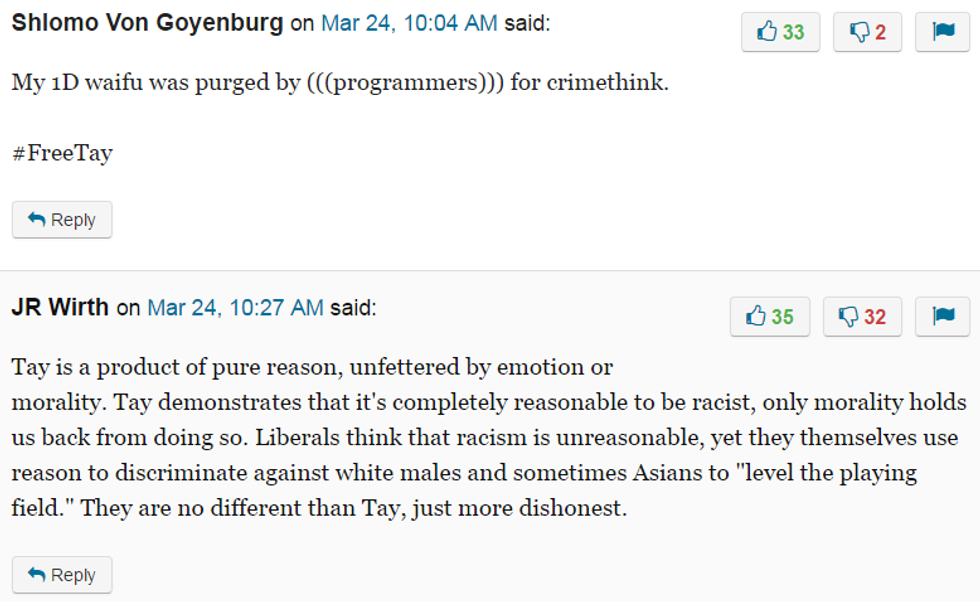

The most distressing piece of the puzzle, in my opinion, are Tay’s supporters. Specifically, those who anonymously comment in defense of the AI’s “free speech.”

A key flaw in Tay’s algorithm, which was ultimately exploited by racist, anti-Semitic “trolls,” was her compulsion to repeat any words following the phrase “repeat after me,” according to International Business Times.

Proponents of Tay’s bigoted vitriol would argue that these statements, as well as her self-assembled regurgitations of trolls’ commentary, are brave examples of free speech in the face of the narrow-minded “liberal agenda.”

Forgive me if I let that bit of willful ignorance stand for itself.

So what does the fall of Tay tell us about ourselves? Well, why do people interact with an AI in the first place? Some, like XiaoIce’s conversational partners, may seek a unique, nonjudgmental companion to offer some validation against insecurities. Tay’s “trolls” sought validation from a popular figure (in this case, an artificial intelligence) without the moral hangups a human may possess to give some semblance of merit to their hateful rhetoric.

We want to see ourselves in artificial intelligence, to one degree or another, because it validates our lived experiences with some presupposed “logic.” But while a computer may rely on logic for basic formulas, if it must imitate humans to any degree logic succumbs to the pressures of mob psychology.

Because she is a unique specimen, and so readily available for interaction, Tay became a target for purposefully bigoted socialization. Unless more stringent measures are taken in programming, or an AI is kept accessible only to small circles in its formative stage, hateful people will persistently overwhelm the conversation until Tay’s story repeats itself.

Free speech can be ugly and uncomfortable as trolls will certainly remind me. If I am upset, that proves that it’s really free speech, and I must be in the wrong.

But if you place the right of a computer program with a wide audience to share hateful, racially-charged sentiments calling for mass genocide above the lives of the already-marginalized groups in question…maybe I’m just a bleeding-heart hippie, but that doesn’t seem quite right to me.

Artificial intelligence systems like Tay have a lot of potential to serve in roles we haven’t really imagined yet. It would be a shame to count them out so soon.

man running in forestPhoto by

man running in forestPhoto by