The events that occurred Nov. 13 were undoubtedly tragic. Innocence and innocents were lost as evil terrorized the setting of one of the shining beacons of liberty and freedom.

It is impossible not to empathize with the pain and anguish that a nation is dealing with in the days since this attack. But, what were we all doing after Thursday? Members of the Islamic State acted out a bombing in Beirut, Lebanon, on the evening of Nov. 12. The location was not too different from the attacks in Paris: a busy shopping and restaurant street. It was the largest death toll since Lebanon’s Civil War in 1990.

Articles read politically, with titles referring first and foremost to the militant political group Hezbollah rather than the humanizing aspect of the tragedy. The second of the two bombings in the attack came from a bakery, not exactly a symbol of Hezbollah’s support of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. This was an attack not only on Hezbollah, but on the people of Beirut’s way of life. So, why don’t we see this attack (along with the endless acts of terror throughout the Middle East and North Africa) as an attack on values? Beirut and Paris are closer to each other than Spokane and Atlanta, but why do we separate the two tragedies as an assault on our beliefs and a political power struggle?

There is an inherent need for people to be able to easily identify with those with whom they empathize. Even though some of the loudest voices in our country have boycotted France and called french fries “freedom fries," Americans are united in showing their support, as is the Western world. Monuments and landmarks are donning the red, white, and blue of the French flag. Sporting events are holding moments of silence (albeit with cringeworthy and Islamophobic results).

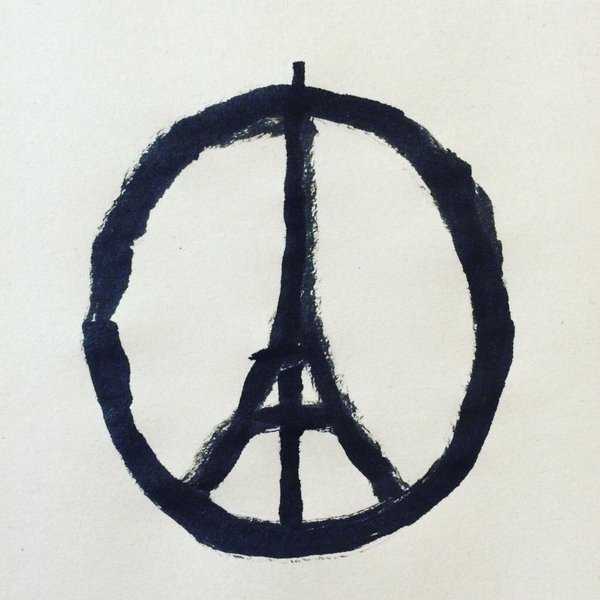

It took less than 24 hours for people to try to find solace in imagery that fit their narrative and offered some sort of alleviation. Tweeted images of the Empire State Building lighted red, white, and blue (which was from Veterans Day rather than Nov. 13) and video of the Eiffel Tower going black (which was after the Charlie Hebdo attack) filled timelines. The now iconic image of the Eiffel Tower aiding in the composition of a peace sign by Jean Jullien was quickly and inaccurately attributed to acclaimed street artist Banksy. It subsequently became the avatar of choice for empathizers on seemingly all social media platforms. That was until Facebook’s French flag overlay.

I am not going to question somebody’s harmless intent to articulate tragedies or process their grief. Nobody grieves the same way. But, I cannot see these attempts as anything more than grieving. Posting an anecdote or changing your picture does not aide the victims of a tragedy, especially one with such lasting implications.

With the many comparisons and allusions to the world after 9/11, an important focus needs to be on how we handle this moment. Candidates on both sides of the upcoming U.S. presidential election are posturing for the terms used in these acts of terrorism. A Canadian Sikh has already had a photo altered to look like a suicide bomber. But also, we must consider the implications on foreign policy for not only our nation but the rest of the world.

On Sunday, French Minister of the Interior Bernard Cazeneuve said the government will look for “dissolution” of “radical mosques.” The Democrats in their debate agreed that the U.S. should agree to take more Syrian refugees. Meanwhile, Republican Sen. Marco Rubio told George Stephanopoulous on ABC News' “This Week” that it was impossible to safely accept refugees because of background check concerns. And, on Sunday, the French military performed an airstrike on an ISIS stronghold in Raqqa, Syria. It is hard to consider a “massive” airstrike that does not include civilians.

There is also the struggle of border control and reform for the European Union. With the incredible amount of refugees coming to the continent and the transcontinental networking that seems to occur for these terrorist cells to operate - terrorists in the Nov. 13 attack and Charlie Hebdo attack planned and came from Belgium - how do you maintain your border policies? Will European citizens be willing to surrender their Schengen visas? Tens of thousands of workers cross borders to work everyday.

So, if we as a people are moved to speak and commiserate over of the horrible events that occurred on social media, we must look beyond just empathy.

If we are to consider the harm that ISIS inflicts throughout the world, we must formulate a revised interpretation of the horror that occurred Friday. ISIS does not attack Western beliefs. ISIS attacks what is not ISIS.