I always assumed that if an injury was going to end my ten-year-long soccer career, it was going to have to be epic.

Not like "Meet the Titans" or "Million Dollar Baby" epic, no, nothing that would involve that kind of drama. But something epic. Maybe a collision. Or a fight on the field. Or a slow motion fall to the ground, with some violins blasting in the background and the soccer moms screaming in agony as I raised one final fist in the air. Something like that. I mean, if an injury was going to prevent me from finishing my senior season, from playing the game I loved, it was going to have to be a crime that could match the punishment.

But all it took was a quick cut. I heard a pop. And that was it.

According to the National Academy of Sports Medicine, The ACL, or the Anterior Cruciate Ligament, is the ligament that creates knee stability. It runs from the lateral femoral condyle to the medial tibial plateau (the thigh bone to the shinbone) and it’s role is to counteract the anterior translation of the tibia on the femur (the shinbone from sliding too far forwards). It prevents hyperextension of the knee, excess valgus forces (or the inward bend of the knee), and when torn, it prevents athletes from playing the game they love for over six months—depending on the severity of their injury.

The tear itself, or that dreaded “pop” happens for two reasons: a quick motion, such as a pivot, cut, sidestep, or awkward landing, or direct contact from other players.

And the worst part of these ACL injuries is the pure fact that they aren’t epic, or rare, in the slightest—in fact, they happen all the time.

According to Boston’s Children’s Hospital about 400,000 ACL related injuries occur in the United States every year, which makes it one of the most common orthopedic surgeries in the United States.

ACL tears are not severe because there are mendable. Eventually, athletes do usually find themselves back out in the game. But the injury has been notorious for ripping away scholarships, and senior-year seasons, and time on the field, the chances for a stable ligament.

In the world of sports, the sound of that “pop” is practically a cuss word.

But doctors at Boston’s Children Hospital have recently released information that they may have a better alternative to the ACL surgical process.

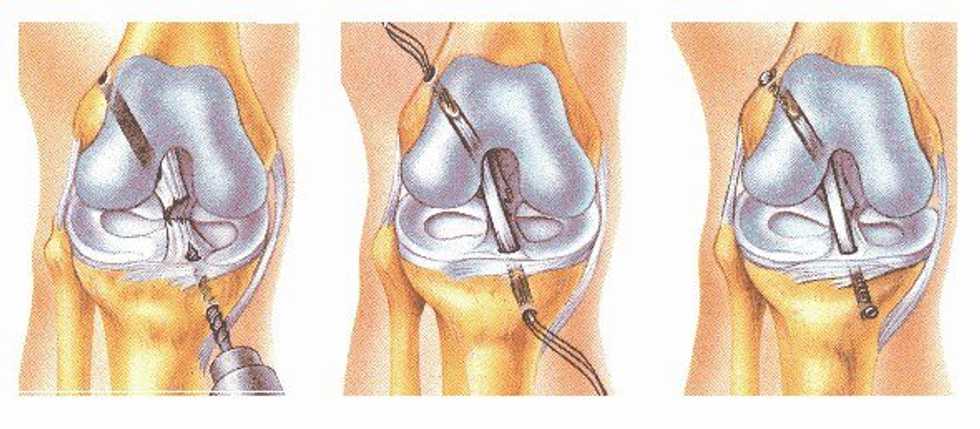

The typical ACL reconstruction goes like this: A surgeon practically “rebuilds” the ligament by harvesting either an allograft (a ligament or tendon from a cadaver) or an autograft (a tendon from the patient’s own body—usually a hamstring or a patellar tendon). The surgeon will then remove the torn ACL, clean the area, and then drills small holes into the tibia and femur, and proceeds to graft the tendon—you can see whole ordeal—with use of the patellar tendon—in the video below:

In summation, the modern-day ACL surgery now consists of a reconstruction, a total rebuilding of the ligament by use of another tendon. The rehab is extensive since the patient must both recuperate from the reconstruction, and if an autograft is used, the strain of the muscle the tendon was taken from. In addition, almost 80% of the patients who go under the reconstruction develop arthritis 15 to 20 years after the surgery.

But the new technique, called “called “Bridge-enhanced ACL Repair (BEAR),” consists of a regeneration of the original ligament. Which means there's no use of an autograft. In addition, Dr. Martha Murray and her team at Boston Children’s Hospital also hope that they can decrease the amount of patients that develop arthritis.

The BEAR procedure goes something like this: instead of a graft, surgeons put a soaked sponge between the severed ends of the ligament. Ultimately, this sponge acts as link between the ends, and in six to eight weeks, the hope is that the ligament grows back together. You can watch the procedure in the video below:

Murray and her associates have performed a trial of the experiment on ten patients, and so far the ligament has been successfully regrown in all ten. None of the participants contracted an infection, and none of them have reported stiffness.

One of the participants, Corey Peak, 26, was running on the treadmill three months after the operation.

Although this operation has had success, experts are still cautious.

“This is definitely an advance but I don’t think we will know for three to five years whether this technique is really effective or not.” said Dr. Jo Hannafin, a senior attending orthopedic surgeon at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York. Hannafin did not partake in the experiment.

In addition, the attempt to reuse the snapped ligament has proven faulty in the past. Surgeons in the 1980’s attempted to restitch torn ACLs but after five years, only half of those knees remained stable. You can read more about BEAR in the New York Times and Boston Children’s Hospital’s webpage.

But if the experiment proves viable, BEAR could be the solution to a shorter recovery time for athletes, and also the solution to a longer, healthier knee.

It could be game changer.

Wait....no. It could epic.