And so now in the spring of 2016 we find we are no better off than those poor boys who first dropped the big one off the creek beds of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. In 2016 we’ve officially forgotten the one thing from almost 15 years ago, the one grand and smoldering grey sky-colored New York day that we as a nation said we would never forget. Continuing to fight two wars out in the Middle East, and nobody wants to talk about the death that keeps heaping itself grandly upon more death. Refugees, leftover from Syria, now pawns to the violent hair-split in France, and what am I to do as a 25-year-old college student, whose only talent is that I can pen some words of middling worth? Who was at fault here?

If God had known what evils the kids were capable of playing on themselves, would he have allowed them access to the toys cooped inside Pandora’s toy chest?

War has insisted upon itself since Cain killed Abel—for all my pleading for pacifism, I cannot deny the necessity thrust upon a man stripped of all choice and forced to defend himself along with those closest to him. That Tuesday morning in September stripped my country of more than its choice; it stripped her of her sanity. Just like when we dropped the atom bomb on the boys of Japan for what they did to our Hawaiian harbor, we find now that we’ve lost our ability to switch off, shut down, give up long after the violence was silenced.

Kurt Vonnegut, who was a POW during the Second Great War and therefore has every right to whine, more than once had said that the dropping of the bomb was the point at which he lost his innocence. “After the thing went off,” he says in his novel "Cat’s Cradle," “after it was a sure thing that America could wipe out a city with just one bomb, a scientist turned to Father and said, ‘Science has now known sin.’ And do you know what Father said? He asked, 'What is sin?’”

The problem goes much deeper than that: it’s not that those who have the power don’t know what sin is; rather it is that they know and just don’t care.

Compare, then, the general lackluster appreciation that came after the bombings at Hiroshima—actions which were probably the only ones we could take, and I have no right to judge. Compare this to the behaviors we enact in a post-9/11 American society. I can no more deny that those terrorists did us wrong than I can deny that the Japanese did us horrible and irrevocable damage; I realize that when the lonely child gets his face shoved in the dirt by the bully, eyes must remain alert for the inevitable strike. But where do we go from the just cause to broaching upon a landscape painting of destruction of those who had nothing to do with the attack? When does the victim become the bully? Who cares enough to ask?

Who cares enough to listen when the screams of 1,000 children come and sing across the radioactive ruins of the deep?

Now we find ourselves fast approaching oblivion; almost 15 years after the Towers fell, and are we any better now than we were that chilled summer day, just a week or so before autumn could start and send us shivering closer to the cold, wintry abyss? A body can only house so many deaths before the soul wonders if he’s going to hell; a man in the prime of his youth can only ask so many questions before he must demand answers to set him free.

The Japanese were a legitimate enemy for sure, mounted and ready to give up their lives to end us completely at Pearl Harbor. The terrorists hovelled together in organized troops somewhere off the Afghani boarder became a legitimate enemy as well, doing the same thing in destroying the World Trade Center on that clear September morning. In both cases, the U.S. went crazy, and justifiably so; when you back that snake in a corner he’s bound to strike.

But consider the countless Japanese-Americans: mothers, fathers, and children, their allegiances for the Red, White, and Blue; some who even took up arms to fight the enemy; who were put in internment camps for the crime of being yellow-skinned.

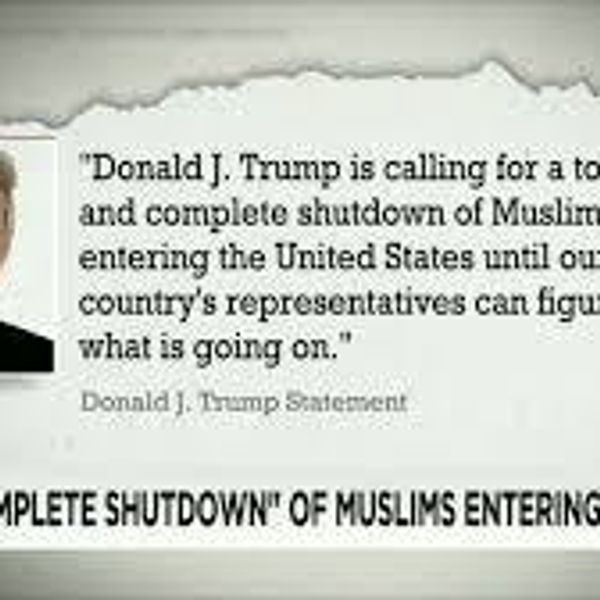

Think of the Muslim-Americans now, some who might be your neighbors, or fellow students alongside your kids, or sitting across from you at the restaurant—looked upon not with the eyes of welcome but rather with the condemning glares of hateful men.

This is not the image of a country hoping to win a war with a cause beyond argument; this is a perfect rage seeking to destroy with its awesome and perverse sense of vengeance.

I was 11 when I lost my innocence that Tuesday morning; I remember running home to my parents, tears streaming down my face, when I asked them, “Mommy, daddy, why do they despise us so much?” Of course, I knew what bullies were capable of; I had enough black eyes and sleepless nights spent crying myself till morning to prove that there were some people who could not allow me to live with dignity. But this was different; this was hate on a larger scale.

It was almost 15 years ago when those towers fell. I’d like not to forget, but to my shame, I realize that at some point I shall. That’s the nature of the beast, but can we do no better by ourselves than to allow the hell of what hurts us to carry us over the edge? For the love of God, how many bombs must drop before we finally kill the world, and ourselves along with it? Would we then finally hold responsibility, when nobody is left to mark the tally?

Good Friday is long over, and Saturday is closing on its end. Do we stand a chance at resurrecting the dead at the end of three days? The pale horse approaches, and hell followed with him.