Recently we have seen a rise in the production and popularity of comic books. This may be due to newer storylines and built-in “jumping on points,” but it's primarily because of the modern superhero/comic film, with hits like Iron Man, The Dark Knight, The Avengers, and X-Men all being highly successful projects in both industries. However, this was not the case twenty years ago. At that point, Marvel was still working on fixing the mess that was the “Clone Saga” in their Spider-Man titles, DC was about to drop what is essentially a film equivalent of a nuclear bomb called Batman and Robin, and the independent companies all were trying to be “edgy” and “cool.” To this day, the effects of the 1990s on the comic book industry are still being felt, and looking back, one could ask why the genre even was able to continue.

We cannot discuss the 1990s and comics without first looking at the late 80s. Starting in 198-, Marvel published a year long series titled Secret Wars,The following year, DC Comics published Crisis on Infinite Earths, which served to essentially reboot their canon for newer readers and to streamline it for older readers. At this time DC also was publishing darker stories, such as The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen. The genre was stepping out of the Bronze (1970s-1980s) and Silver (1950s-1970s) Ages, and into a newer, more adult era (occasionally referred to as the Copper Age or Modern Age). Independent publishers, such as Mirage and Dark Horse, were starting up as well, releasing titles that were targeted to a much older age than the stereotypical “comic book reading kid.” As the decade went on, the Big Two were inching into even darker territory. Marvel introduced the Spider-Man villain Venom, and DC killed off the Jason Todd Robin in the seminal Death in the Family story. The release of Tim Burton's 1989 film Batman helped to reestablish the character as a shadowy figure in the night, far from the still well-known 1966 Batman television series starring Adam West.

In 1990, comics started picking up more and more readers, thanks to Batman and heavy promotion from Marvel. DC and Marvel ran new miniseries titles, being Infinite Crisis and The Infinity Gauntlet over the next couple of years. Soon afterward, DC brought in the next Robin to give closure to the Death in the Family arc, while Marvel started to publish the 2099 series, reimagining classic heroes in a cyberpunk future. However, all was not well at Marvel. Many writers and artists felt that they were not being paid enough for their work, and were concerned over their new creations for the comics – whatever they created for the Marvel title they were working on, it belonged to Marvel. A group of creators, including Jim Lee, Todd McFarlane and Rob Liefeld, quit Marvel in 1992 and established Image Comics, a company that would allow the creators to keep all rights to their work, essentially acting as nothing more than a publication house. Over the decade, Image Comics released famed titles such as Spawn, Witchblade, and Savage Dragon.

Comic storylines are just companies fighting each other to try to be the better story. Seeing DC's successful with shaking up Superman and Batman, Marvel commissioned the Spider-Man team to come up with a story that would bring changes to Spider-Man himself. They settled on The Clone Saga, where the original twist was that Spider-Man was actually the clone Spider-Man from a 1970s story. This twist got an immediate negative reaction, and the writers had to try to fix it so that the clone was not actually Spider-Man after all. At the same time, they had plans of introducing more villains, but they were shuffled to becoming simply minor supporting characters that would phase out of the comics over the next few years. While the plan was always to have the “Peter Parker isn't the real Spider-Man” twist to be revealed to be a ruse, the writers were being faced with deadlines and attempts to get things back to normal, all while trying to run the four Spider-Man titles with a single continuous story. This caused a story that should have wrapped up in a year to take several. The now infamous Clone Saga featured some well-received elements, but the main story itself is often seen as flawed and just Marvel trying to compete with DC, and failing at it.

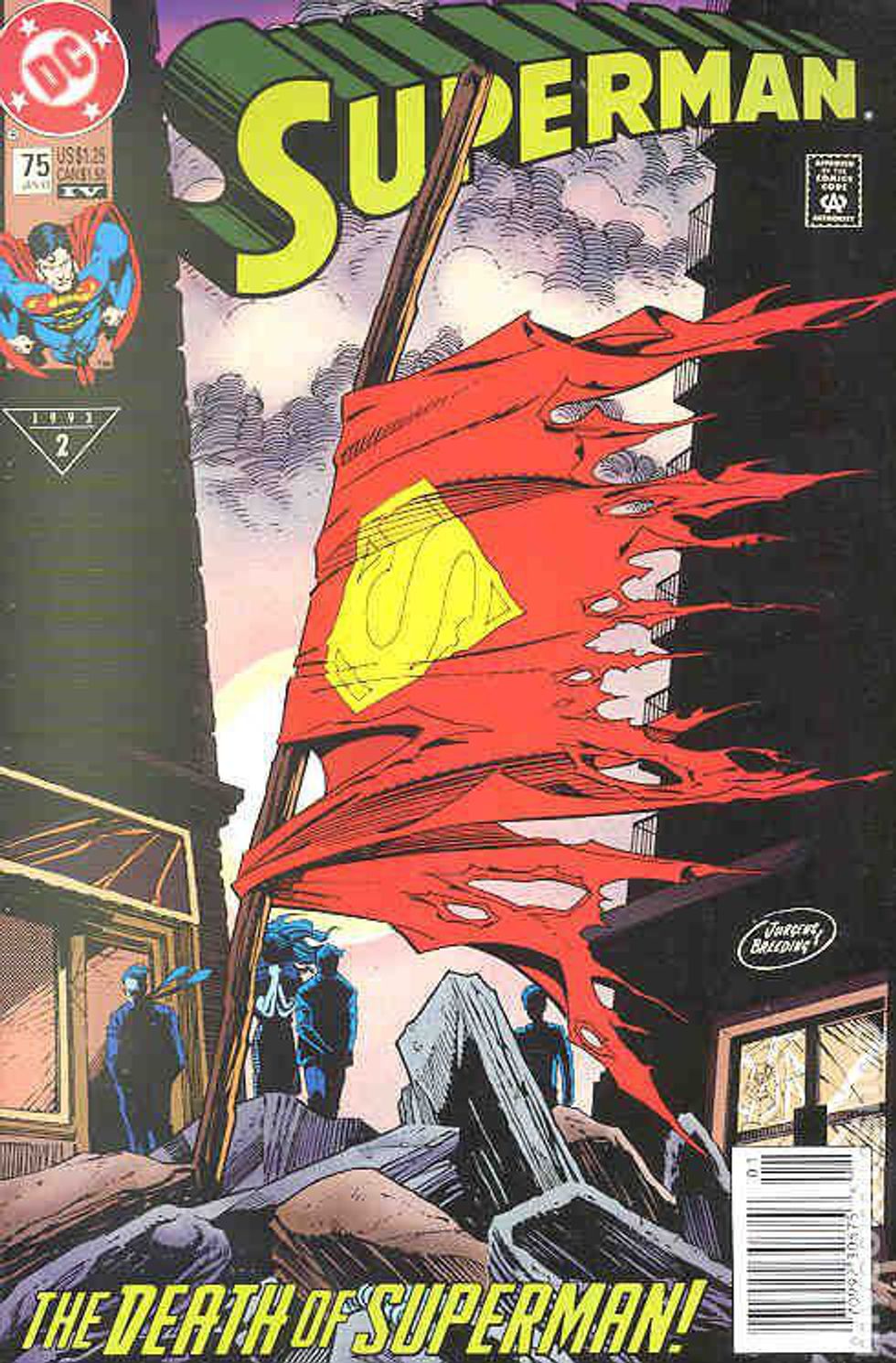

The increase in publication and public interest brought on the rise of the speculator market. New comic series would have a “#1 Collector's Edition First Issue,” as it was assumed every first issue would be worth as much as Action Comics #1 (first appearance of Superman in 1938). Marvel is the most guilty when it comes to playing to the speculator market, with regular “foil” covers (similar to foil baseball cards) for new titles and multiple variant covers for said titles – all to convince people it would be worth a lot in a few years. One famous example is the 1991 X-Men #1, which had six different covers, and if one bought all six and put them side by side, it would form an image of the X-Men fighting Magneto. But the contents of the issues weren't changed, so people were buying multiple copies of the same issue just to have a complete set they could sell off in the future for thousands of dollars. Because of this, anywhere between 8 and 12 million copies were sold, a record that still stands to this very day – driving the value of the issue down to less than a dollar in some cases. Image was more subtle, and they didn't have the money to promote new titles, so it was up to the creator to decide if they wanted to play to this market. DC's Death of Superman also was a major aspect of this practice, with the death issue, Superman #75, selling in mass numbers and special sealed bagged “collector's edition” comics being produced and sold for more than the unbagged book. Much like X-Men #1, DC ended up driving the value down to less than a hundred dollars (at last count).

This of course brings us to Marvel's bankruptcy. Following the Image Comics fiasco and the mass publication of X-Men #1, Marvel was loosing more money than they were bringing in. To counteract this, Marvel began trying to recoup losses by selling film rights – even after the 1990 failure that was Captain America. The rights to X-Men, Fantastic Four, and Daredevil were sold to 20th Century Fox. The rights to Spider-Man, which Marvel had just got returned, were sold out to Sony, along with some other characters, such as Doctor Strange. Film had the exact opposite effect for DC. While Batman Returns in 1992 was a success, the film was deemed too dark by studio executives, which made Tim Burton be shuffled to a producer credit while Joel Shumacher was brought in to direct Batman Forever. When that film proved to be more family-friendly and marketable, Warner Brothers wanted to make the sequel even more “toy friendly.” This of course is what became the root of all issues with the infamous Batman and Robin – the studio cared more about selling toys than they did about making a good movie that kids would want to buy toys from. DC was also working on adapting the Death of Superman story into the Tim Burton directed Superman Lives, but by 1999, the project was quietly shut down weeks before final casting was to take place. Instead, the character of Steel was given his own solo film, and while it may be a bad movie, at least it's not Batman and Robin.

Despite all this, it was not all bad. Marvel and DC published a series where they pitted their universes' characters against the other, the first time in years They were doing well with animated shows, including Batman: The Animated Series and Spider-Man, the former of which introduced Harley Quinn to the DC Universe.Toys of the characters were also high selling products. And even though there was little faith in the superhero film genre, Fox was moving forward with an X-Men film. While the comics themselves were going through many problems and de-valued because of massive printings, the companies were finding footing in other endeavors. Image Comics and Dark Horse were catching on, and independent comics were being treated as serious competition. It is surprising that in less than twenty years, the industry has gone back to an era similar to the 1970s – amazing stories, a care for the reader, and letting key issues become keys on their own merits, not because of a label attached to the cover. The effects of the 1990s on the industry are still prevalent – big story arcs for characters and a ton of #1 issues, but we've made it out of the decade of uncertainty and proved the industry can continue.