I wasn’t originally amused by Harambe. It was a tragedy: a great ape struck down by fell circumstances. It was a death in the style of Cecil the Lion, being unnecessary and symbolic for the abuse animals have suffered at the hands of humanity. Not that the death of Harambe, which seems to have been justified, can compare to the senseless killing of Cecil; it is simply that, regardless of the circumstances, two great animals were put down by humans. I was also unamused by the first pop-culture reactions to Harambe’s death. The “dicks out for Harambe” meme seemed typically vulgar and nonsensical. But as the movement, if I may call it so, has evolved, it has become more tasteful—and a whole lot funnier.

The level of Harambe jokes that have arisen in the months since his death are on a new level—far above that of “dicks” being “out.” These jokes have wandered into the land of tasteful wit, amusing puns, and cross-cultural references that make jokes truly funny.

To name a few examples:

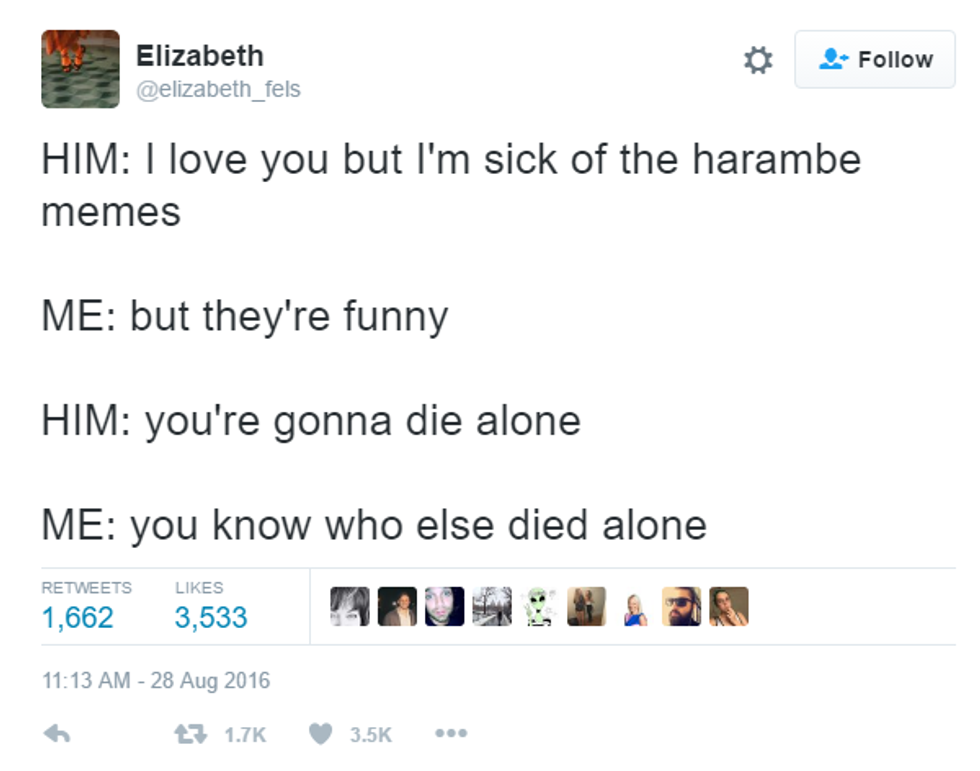

Tasteful wit:

Amusing pun:

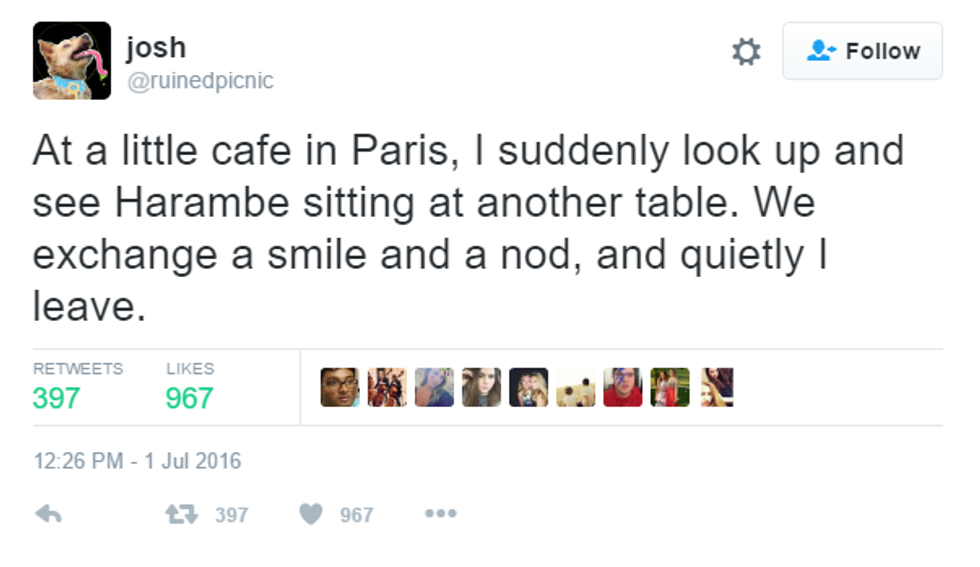

Cross-cultural reference:

True humor took over the raw anger and release of stress pulsing through the Harambe movement. Excellently sharp jabs and cutting ripostes are the norm for Harambe fans now, and it’s a sure improvement over the brusque vulgarity of “dicks out for Harambe.”

The rise of this sharp style of humor is increasingly evident today, from adult movies to children’s adventures. The recently released Kubo and the Two Strings has a few flashes of inspired wordplay between its protagonists. Most notably is an interaction between the bickering Beetle and Monkey, wherein Monkey complains about giant monsters that steal one’s soul if eye contact is made. Beetle, quick to respond, gives her a smirk, says, “Then I won’t look them in the eye… even when I’m being sincere,” and hops into the ocean without a splash. The scene is short, the animation taking a background to the dialogue, but the interplay is excellently timed. The effect is akin to a small bell being clearly struck: it is not a tolling, time-consuming exchange, but one that leaves a sweet ringing sound and brings a light sense of appreciation to the audience.

Wordplay like this hasn’t grown alone in the worlds of film and Twitter. One of the characteristic aspects of rap music is wordplay—from Eminem to Shahmen, rappers use their words to paint verbal pictures of their woes, hoes, and foes. To provide an example, Hopsin’s diss of his ex-record label manager Dame Ritter brought together some sick lines.

“But you don't understand the culture of hip-hop

You a lame ass nigga Dame, half the crew knows

New age Jerry Heller, a scary fella

I hate your fucking name, every letter

I'm very fed up, you acting like an ordinary heffa

I'ma take you to the mortuary dress-up.”

Hopsin calls Ritter a Jerry Heller, the music manager cited as responsible for the collapse of N.W.A, followed up by comparing him to a “heffa”—generally someone who doesn’t know when to stop and goes too far, often referencing gluttony—which is even a cleaner diss because of its preceding line, “I’m very fed up,” given the association of the word “heffa” with over-eating. And, naturally, Hopsin cleans it up with a reference to being dressed up for his deathbed—a threat, no doubt—but well-spoken and cleverly presented.