The Issue:

Responses to a new French law that requires models to maintain a certain BMI have been, to say the least, expected. Models putting weights in their hair to make the mark is a true demonstration of the issue’s complexity. The reality is that a person’s mentality will not change because of a threat. The fashion industry, as an entity, has endorsed a certain “look” for years and it will take more than forceful regulation to resolve a body diversity problem that comes with decades worth of penetrating ideology by the fashion world.

As of early 2016, the UK brand Rose & Willard has bounded models to eat by contract. Not only will they be required to do so in order to receive compensation, they will be monitored before and after shows. The intentions of new regulation such as these are to ensure that models are not seeking unhealthy measures to make the runway’s mark. But even regulation such as these, when standing alone, lack the capability to do extensive change.

Since the 1960s, the fashion industry has been scrutinized for promoting a singular image; one that many models themselves cannot attain or maintain. For decades, slender, long and lean has been the symbol of success on runways and magazine shoots. The look can be beautiful, but many times in the industry, it's the only body type represented as such.

To ignore that parts of the media and style industry has not made an effort to promote other body types is to be unfair; recent covers of Sports Illustrated feature curvy and strong women like Ashley Graham and Serena Williams, displaying them as central components to “Curvy is Sexy” and “Love your body!” campaigns.

Even the Aerie clothing line by American Eagle has made a significant step toward embracing a new era of body diversity and positivity, using full-figured English model Iskra Lawrence as their newest campaign girl.

To say it has improved completely, however, would be just as unfair. Still today, these campaigns represent a minority in the fashion realm. Jobs are usually rewarded to thinner models like Kendall Jenner, who has become the face of high demand brands such as Calvin Klein, paid to embellish their Instagram of 50+ million followers with bared body shots of their slender frames, targeting the most vulnerable of consumers.

For the runways, average weights of models between 5’9- 6’0 feet, range from 110-120 pounds, averaging measurements of 34-24-34 (which is not far off from a life-size Barbie, with a much smaller bust.)

Holiday, Graham, Williams and Lawrence may be dawning cover pages now more than ever, but the adverts from brand such as YSL and Givenchy, displaying girls that seem starved and Photoshopped, maintains a fundamental presence in the magazine edition itself.

As a society, progression has been made; there is no arguing that point. As norms have progressed toward a more open arena of thought, so have mindsets, ideals, and intentions. The millennial generation has gone to great lengths to become the most accepting generation as of yet, and living in a world where two men can marry and Barbie can be black, Asian, petite, curvy or tall, is qualified proof.

Yet, there remain battles left to be fought. The #Oscarssowhite controversy and the belittling of refugees on the premise of religion by presidential candidates are just a few examples of holes in an improving system. Diversity may be the word of the century, but its essence has yet to be embraced entirely by everyone.

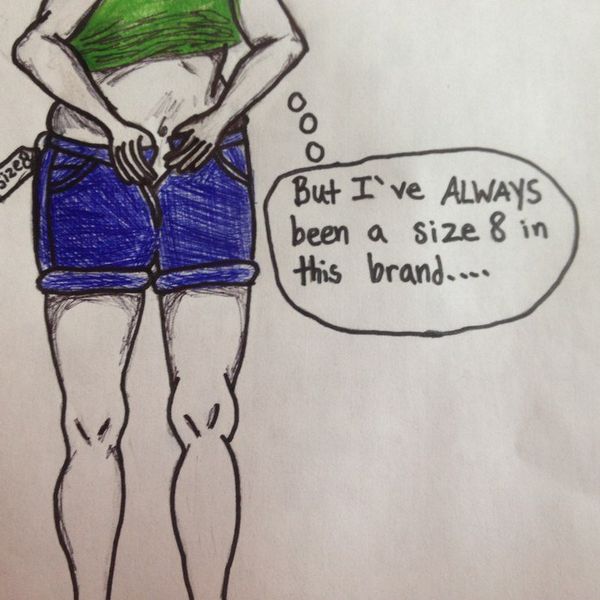

The true dilemma with regards to the fashion industry in particular is that it is sending mixed messages. Branding healthy, curvy or “plus-sized” seems to be all the rage among shape magazines, but as long as runways continue to adhere to standards of decades past and as long as esteemed brands continue to drastically alter models through Photoshop, this issue will never go away. Changing the weight requirements may seem to offer a solution to the problem, but its essence is another method of exclusion and standard setting.

Any model that is not genetically able to meet the industry’s standards without living a life of restriction is so transfixed with the idea that admiration, beauty, and opportunity are products of an incredibly low BMI, that physically forcing food to her mouth is an idea projected for failure.

Only when a woman is not labeled based on her physique and not pressured to consider thin as admirable or curvy as healthy, weight and impressions of what is “appealing” become normalized.

So no, a model does not need to be forced to eat or regulated to be a certain weight. She needs to feel that she will be able to land quality jobs no matter her measurements or BMI percentage.

The only way to end this perpetuating cycle of standard setting, idolizing and comparing in a society so focused on image, is to handle it like any other constricting ideology. That is, to throw out all former regulation. Pay mind to the methods of selection for certain brands, how those brands are represented and the spectrum of people that represent them.

To put it in simple terms: walk the walk. Promoting diversity is only qualified when diversity is actually promoted in advertisements, on runways and among brand ambassadors across the fashion world, not in just one corner of it.

Former model and TV personality Alexa Chung recently collaborated with British Vogue to produce a YouTube mini-series on the “Future of Fashion” which features an interview with fashion commentator Caryn Franklin. When asked about the topic of body diversity, Franklin replied with, “If we had more of a spectrum of beauty, you would be able to hold your position and celebrate who you are as you rightly should be able to. We will be able to see all those mixes playing out-- different body shapes, different ethnicities, and different body types. It’s always a good time for a revolution.”