Mass production has long been understood to be an important part of business due to how it decreased costs of production. When a business produces more units of any product over a set amount of time it spreads its fixed costs (the costs that do not scale with the level of production) across the units produced, ultimately yielding a lower fixed cost per unit. In 1913, a new era of mass production began as the first modern assembly line began functioning to build Henry Ford’s Model T. The modern assembly line enabled businesses in a menagerie of industries to vastly improve their output with a relatively small workforce. You don’t have to be a business major to see the benefit of this system.

This is merely an expression of the logical evolution of capitalism. At the most basic level a business achieves an increase in profits by pursuing at least one of two primary business objectives; decreasing costs and increasing revenue. Simply put, if you decrease costs while maintaining the same revenue or increase revenue while maintaining the same costs, the result is a higher profit. Now apply this concept to mass production. A substantial increase in output per worker translates to a substantial increase in production per labor hour as well as lower fixed costs per unit. Mass production both lowers costs and increases revenue, making it an excellent method by which to increase profits. Considering our culture is highly profit-motivated to the point of profit-glorification, mass production was an inevitable milestone in the development of our economy.

In the early 21st century, as it was in the early 20th century, we are experiencing a new wave of technological innovation perhaps as significant, if not more significant, than the assembly line. Today we are bearing witness to the rise of automation, arguably the logical evolution of the assembly line. In the never ending struggle to cut costs, it only makes sense to investigate the feasibility of running an assembly line without workers. And that is exactly what has been accomplished. Now, admittedly, we have been using industrial robots since 1961 when General Motors began using the first industrial robot as part of an assembly line at a plant in New Jersey. However, today we have advanced to an interesting point in our exploration of automation.

In the United States and abroad, businesses have begun operating what are called “lights-out factories” or “dark factories” where industrial robots work in a fully automated labor-less environment. These factories can work 24/7 and do not take a salary. Yes, there are operating costs, but these costs are substantially lower than employee wages. The end result for businesses is all of the high levels of production of an assembly line, but now with no labor costs. And to sweeten the deal, these labor-less factories can operate perpetually. The machines don’t need breaks and they don’t need sleep. This may be the ultimate evolution of production; full automation with human hands only interceding to alter some programs when the factories need to shift products.

But the reach of automation does not stop there. In the logistics industry, warehouses are staffed by employees called “pickers” whose job is to fill orders by collecting products from their specific section of the warehouse. However their jobs could soon be usurped by machines like the Kiva robot, which decreases the need for pickers by bringing inventory sets pickers need to a station where the picker would be working. You can have a look at this process below:

At first glance these developments might seem as though they are natural and inevitable evolutions of business. From an economic standpoint, it only makes sense that the goal of increased profits would drive businesses to higher and higher levels of automation. But automation requires a much more comprehensive review of its implications before we applaud our technological prowess. If we assume that businesses’ profits are the ultimate end goal, then automation is certainly creating a great future for us. But if we shuffle our values and make a sustainable and stable society our end goal, suddenly automation becomes a little counter-productive.

If we look at fiction, the promise of robotics technology and automation is a greater standard of living for all, as work becomes unnecessary for people because machines do all of the tasks that once required a human being. But in practical application businesses are utilizing automation to enhance their profits to the detriment of the populace. It is undeniable that automation decreases costs and thus prices of products on the market, but it also trims of more and more jobs from the labor market. If this is carried out to its logical conclusion, you would see wealth concentrated heavily in the businesses with automation while hordes of poor disenfranchised former laborers plot violent uprisings. That assumes, of course, that these resources are not nationalized so they contribute to society.

Ultimately, automation may be a clever and revolutionary means to higher profits and cheaper market prices, but it’s the worker’s bane. And this strikes a chord with the history of labor relations in capitalist economies the world over. So do we consent to more and more automation despite the fact that is will destroy jobs in the name of corporate profit? After all, it is not the responsibility of a business to make sure it pays out money to laborers as it takes in money from society. The role of a business is to make profit. If it doesn’t WANT to be responsible to society as well, it doesn’t have to. Unfortunately, if we’re going to make the best use of automation, we need to abandon the notion that a business’s only job is to make profit. Sorry Milton Freedman.

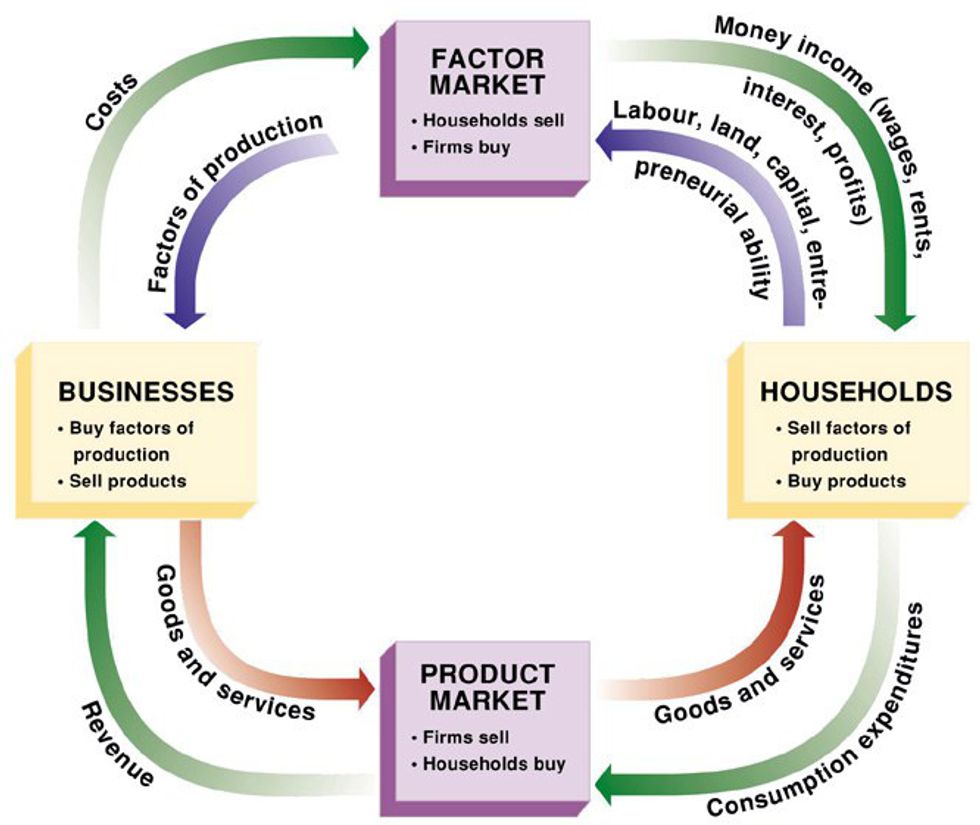

Automation when joined with labor maintains jobs and improves the bottom line. Total automation is unacceptable. For those who would argue against this assertion because the only goal of business is to create profits, I would like to redirect them to the purpose of an economy. An economy is meant to provide a better standard of living for the people in that economy. Businesses within said economy, then, must serve the purpose of improving the standard of living of the people in the economy, not just accumulating wealth. Why? Because in the basics of economics we can see that wealth is never meant to be accumulated in vast quantities. Observe this model of the flow of money and capital in an economy:

Automation has the potential to become a pivotal battleground in the fight for our economic culture. Do we focus on providing a better standard of living? Or do we continue to glorify whoever can get the most money? The idea that business’s only goal is to make profit is nothing but a canard with pseudo-philosophical backing meant to convince people to allow those with power to use it to squeeze as much money as they can out of consumers, laborers and anyone else that can be squeezed. Saying a business should only work to increase its profit is like saying that the human heart should work to accumulate as much blood as possible.