“You don’t look like a Tyrice,” a classmate said to me smirking through squinted eyes. Her tone suggested that my name was too black for my physical appearance. She had known me for less than five minutes.

In my head, I thought, what does a Tyrice even look like? Can he not look like me, a Guyanese and Black person? Is he supposed to be darker? Should he look like a hoodlum? Have more swag than I (impossible)? Is he a caricature? Does he wear Enyce? Because of her inflection, I was flattered to be considered the opposite of my imagined stereotypes.

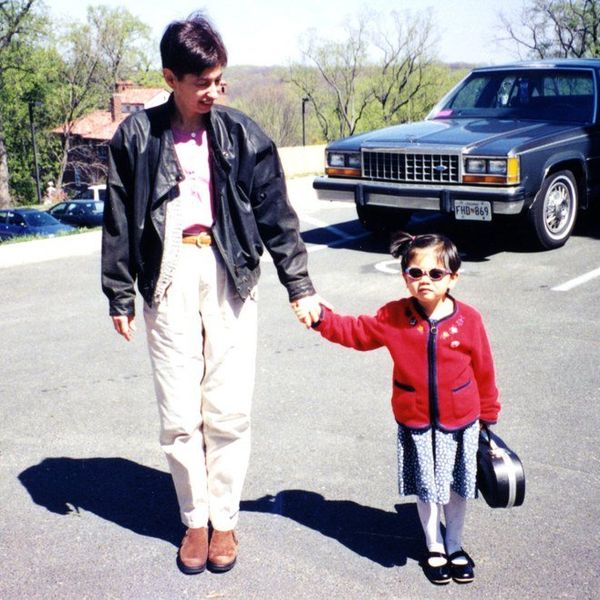

Places like the classroom would puzzle me growing up. Instances like not looking black enough for my black name would make me feel ostracized to where I didn’t feel included within my own community. I didn’t fit the standard idea of blackness, therefore I wasn’t like my counterparts. Sometimes I would even negate my blackness. I have since grown out of that narrow-minded notion and have embraced the multicultural African diaspora. In doing so I’ve realized how colorism operates within our community.

I’m aware that as a lighter skinned black person, I have the ability to ignore the colorism conversation entirely, whereas someone darker cannot. My skin color has granted me a privilege that constantly needs to be checked.

Where you fall on the hue spectrum in the black community legitimizes your lived experience. Our country’s history of internalized racism has historically allowed mixed/biracial black people to receive preferential treatment due to a closer resemblance to Eurocentric standards of beauty.

Differential treatment based on skin color and phenotype is called colorism, and it’s apparent in a variety of ways within the black community. In our society if you appear to have European or mixed lineage you hardly go unnoticed. Maybe you’re teased for being too light skinned, but being called “high yellow,” “lite-brite,” or “redbone,” is hardly a derogatory statement in comparison to terms like “darkie” or “tar baby.” Light skinned people are glamorized and thought to be more intelligent beautiful and less threatening than darker skinned people.

The preferential treatment granted to those with lighter skin tones and “exotic” features shun those who don’t identify with such. I’ve never had members of the black community tell me my skin tone is too dark. I’ve never had my complexion compared to a Nestle bar. Never struggled with (or not) the idea that I have a deficit because of higher levels of melanin or had to be reassured that my skin color was beautiful, by my community, in an effort combat bias. I’ve never had to attend a press conference and say give people with my skin tone more opportunities.

As one in a handful of black students in a predominantly white elementary school, I was able to excel in some areas based on these traits alone. In fact, because I was racially ambiguous, I was less likely to be disciplined harshly and suspended. I remember receiving preferential treatment from teachers because of my (then) excessively curly mane.

The fact that I felt separated from my community based on my physical appearance is shameful, especially when there is room for all people of color within the African diaspora. I’m still identified as black by virtually everyone outside of my community. Despite an ascribed status granted to me because I am mixed, I’m not immune to “you’re hot for a black guy” rhetoric on dating profiles.

When Andre 3000 donned that black jumpsuit in 2014 that read, “Across cultures, darker people suffer most. Why?” the Internet lost their minds. Besides hitting the reblog button on Tumblr and the heart icon on Instagram the sentiment behind the message resonated deeply to some of us who have lived through it. To not acknowledge the privilege of having a lighter hue is akin to white people not checking their privilege. Our community cannot stop having this discussion.