Freedom is essential for an American democracy. From the beginning of our Lockean, elitist beginnings, it has been an essential part of our system of governance.

It is assumed over and over again that we must be free to choose right and wrong, that we must be created neutral before God and men and that we are the summation of our choices, for at least the pragmatic necessity of daily functioning and economic autonomy.

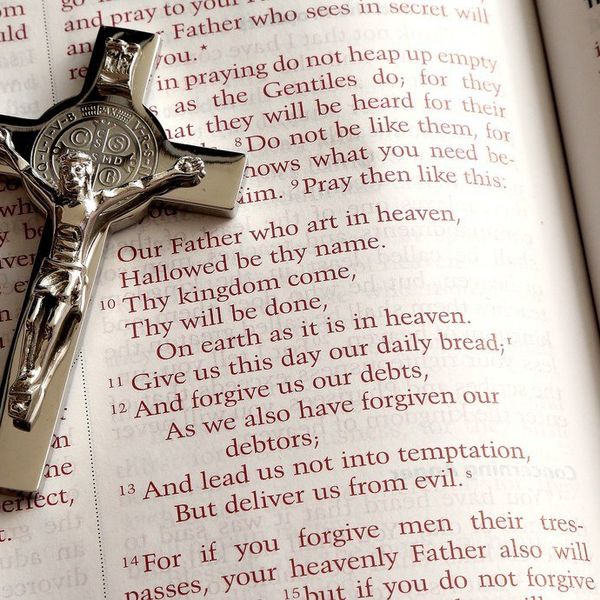

But is this freedom biblical? Does the Bible really say that our will is free?

Here, I will attempt to paint a picture of Christianity’s relationship with the concept of “free will,” the “Liberum Arbitrium,” and its non-biblical, necessity-driven synthesis with Christian doctrine.

First and foremost, it is helpful to think about Christianity as, from the start (though not exclusively), Jewish.

The Old Covenant was given to Jews; this Old Covenant was completed by the New Covenant, which was given (not-exclusively) to Jewish Christians. So, it’s important to look to see how the Jews used words like “freedom” and “autonomy” if we are to accurately locate a distinctly Jewish (and, thus, “Christian”) conception of free will.

However, there is a massive problem with this endeavor right from the get-go: There’s nothing to be found about free will in Judaism.

In the Old Testament, we see a transcendent God who hardens whom he hardens and graces whom he graces. From the beginning of creation (Genesis 1), when God calls being from non-being (the pretentiously academic Latin phrase which is sometimes used is “ex nihilo”) to the end of the prophets, where He promises He will deliver Israel from the oppression of their sins and conquerors (Micah 4), there is no acknowledgement of a genuinely free will.

In fact, when Israel promises Joshua that they will keep the covenant of Moses, their great and noble leader, Joshua turns to them and says, “You are not able to serve the Lord, for He is a holy God” (Josh 24:19).

They are utterly dependent on God! And when Job, the poor, tragedy-stricken man, inquires into God’s ineffable will as to why God allows suffering, he’s not told that it’s in punishment for our misuse of our “free will;” God only refers him to the fact that God is God! These are tough passages, to be sure, but one thing can be said of them: They allow little room for any concept of “freedom” or “autonomy.”

So, where do these words come from, and how did they creep into our Christian vocabularies?

Probably the first place you’ll find these words cropping up in theological polemics is in the Patristic Period (approximately 100-429 AD), and that’s because the first few centuries of Christian thought revolved around the great, apocalyptical development that happened on Pentecost: The Holy Spirit was given to all nations.

Gentiles (that is, non-Jews) are now a part of the New Covenant.

So, right from the get-go, the Church was trying to figure out how to engage the culture around it, and during this time, a particularly nasty road block that got in the Church’s way was what is commonly referred to as Gnosticism.

Though it’s hard to define, Gnosticism can be generally considered a system that is of pagan (that is, “not Christian”) origin, which attempts to depart secret knowledge (especially a secret cosmology) to its adherents.

Gnostics (think Manicheans) usually held to dualist, deterministic systems, which were very hostile to the distinctly Jewish gospel Christians evangelized. And so, the early fathers had a hard time fighting back against these combatants, and a lot of the time, they did this not with theology but with philosophy.

Philosophically, Justin Martyr would employ a synthesis of Plato and the Old Testament to argue that man had freedom (ελευθερία) and self-determinism (αυτεξούσια) against the gnostic fatalists. Philosophically, John Chrysistom and The Cappadocian Fathers would follow not far behind. Philosophically, Gregory of Nyssa would suggest a distinction between structural and functional freedom.

And, Philosophically, Nemesius of Emesa would make the distinction between voluntarium and involuntarium, making actions depend on your consilium.

And then, because the Church also had to engage the Latin West, Tertullian was the man who was burdened with translating all of this Greek into accessible Latin.

And, it was Tertullian who chose to translate the Greek ὑπόστασις (which means "a being subsisting in itself") as persona (person) and solidified the Christian philosophical-theological hybrid concept of vuluntas (the “Will”).

And this is how Christians in the West would talk, at least until the Pelagian Controversy (but that’s another story for another day).

My friends, the bottom line is this: This talk of “free will” is not a Christian idea; it is a pagan idea that has been held by some Christians.

It can't be deduced by looking at the person or work of Christ, nor can it be found in accordance with God’s economy of salvation in the Old and New Testaments.

It doesn't help us better state the mysteries of the Word and sacraments, where we receive Christ in simple bread and wine, by simple water and simple words. It does not convert people as our simple preaching does.

At the end of the day, this liberum arbitrium language does not help us at all; rather, it confuses us into thinking we can somehow appease God by our acts of will as Tertullian mistakenly proposed. It was misguidedly adopted by our predecessors to combat a Hellenistic philosophy, but it has outlasted its use. It is about time we bury the hatchet.

My last thoughts are these, as an echo of the Apostle Paul in his letter to the Church at Rome (16:17-20).

"I appeal to you, brothers, to watch out for those who cause divisions and create obstacles contrary to the doctrine that you have been taught; avoid them. For such persons do not serve our Lord Christ, but their own appetites, and by smooth talk and flattery they deceive the hearts of the naive. For your obedience is known to all, so that I rejoice over you, but I want you to be wise as to what is good and innocent as to what is evil. The God of peace will soon crush Satan under your feet. The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with you."

The God of peace has crushed Satan under our feet.

May we watch and wait for Our Lord’s glorious return, clinging not to our own will, but to His great and gracious will, made known to us in the Person and Work of Christ and delivered to us in his very flesh and blood, the life-giving bread and wine.