Recently, it was reported that Iraqi military forces managed to take back more territory from ISIS/Daesh (an Arabic pronunciation of the acronym that translates roughly to “Liar” or “Traitor”). Attacks have been all over the news while politicians and the like argue over how best to deal with the terrorist organization. I’ve thought about Daesh a few times and I have concluded that they are all a card short of a full deck. I will admit that, at some level, their base motive is justified.

Before you close your window, hear me out.

Daesh states that their end goal is a Muslim utopia free of Western Influence. That has never existed. Open any history book about the Caliphates of Iraq and Syria and you will find that the Muslims drew plenty of influence from Westerners. The founders of the Abbasids were big fans of such names as Galen, Aristotle, and Euclid and the expansion of Baghdad under the Abbasids was partially influenced by Byzantine urban policies and suggestions.

Time and again, Daesh’s actions have been called Un-Muslim by other Muslim powers such as Iran and Saudi Arabia and most of their violence is not directed outward but inward, purging minorities and “heretics” that would otherwise ruin their “utopia.”

This is nothing new. Shia and Sunni Muslims have purged one another time and again since Mohammed’s death, although it’s interesting to note that Islam is, in theory, rather tolerant towards other religions, as they usually set their persecutions to “heavy taxation” instead of “kill everyone.” For a group that says that they want to do away with the West, they’re sure making good use of such wonderful Western inventions such as social media and Western weapons and vehicles.

So, most of Daesh’s motives are rather hollow, but there is one that needs more attention: mainly, metaphorically putting these guys’ heads on pikes.

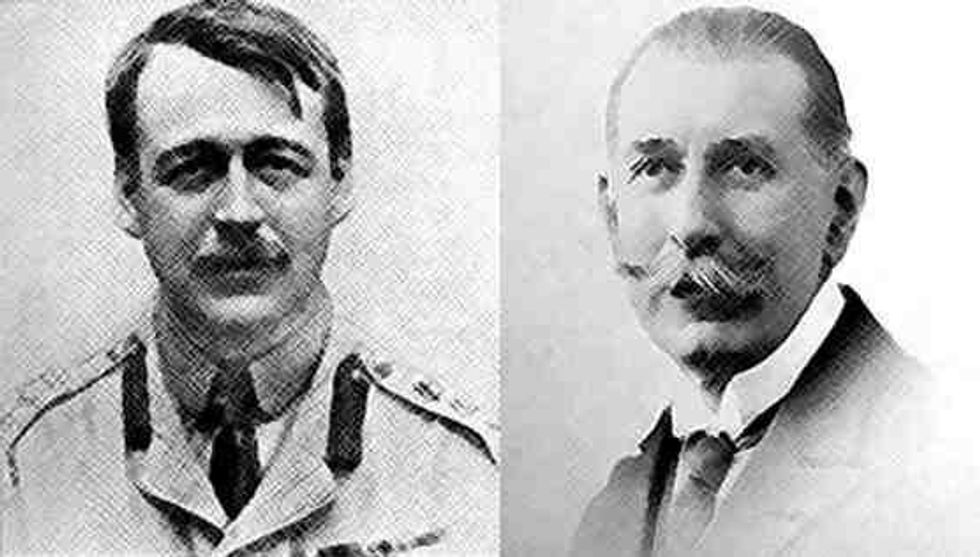

This is Sir Mark Sykes (left) and François George-Picot (right), authors of the 1916 Sykes-Picot Act that Daesh would see destroyed. Why is that? Here's a history lesson.

Way back in 1914, France and Great Britain were trying to coax Arab nationalists to rebel against the Ottoman Turks, who had ruled that region of the world since the 16th century. Through their representative T. E. Lawrence, or “Lawrence of Arabia” as he’s known in popular culture, the Entente powers managed to secure a native army on one condition: when the dust settled and the Turks were gone, the Arabs would be able to form their own independent state.

It would stretch from Turkey to the north to the edge of the Saudi Arabian peninsula to the south and from the Mediterranean in the east to Iran in the west. The Entente agreed, but, as the Arabs marched to war against the Turks, Britain and France pulled out their pencils and maps and began to draw up a new plan for post-war Arabia.

This is what they came up with. The Arabs would get their kingdom, but the British and French would chop off most of the northern regions (which had extensive oil fields). These areas would nominally govern themselves, but they would be overseen by France and Britain. They told no one else of the plan, especially not the Arabs who wouldn’t be getting the full kingdom that they were promised.

Thus, the nations of Jordan, Syria, Iraq, and Palestine (later Israel) were created. The British and French got the areas of influence that they wanted, the Arabs got a little bit of the kingdom that they were promised, and hundreds of soldiers died to make it so. That's the end of the story, right? Well, considering that we’re still fighting over this treaty 100 years after the fact, there’s clearly more to say.

What that map doesn’t show is that, when the new nations were created, they mashed together dozens of ethnic and religious groups that usually don’t mix together. Take Iraq for instance. It’s largely a Shia nation, but under Sykes-Picot a sizable Sunni population was now within Iraq’s northern territories, cut off from other Sunnis in Turkey and Syria.

The Kurds were left out in the cold, also forced into borders that they didn’t want instead of getting their own Kurdistan (which, according to Woodrow Wilson’s "Fourteen Points," they were entitled to). It is not all that different from what happened in Eastern Europe between the World Wars, with new nations being cobbled together out of ethnic and religious groups that didn’t want to be together and that then subsequently tore each other apart once the Germans or Russians rolled in.

What could have been controlled under a larger Arab state was now under the administration of French and British officials, who weren’t interested in things like self-determination. They just wanted someone to give them all of that precious oil out there in the desert.

100 years later, we are reaping what they sowed.

Daesh says that their goal is to destroy the Sykes-Picot treaty and, so far, they’ve done a great job in erasing the border between Syria and Iraq. Their methods are deplorable and their extremism is frightening, but their anger at the plotting and scheming of old Imperialists is fairly understandable. Deash is not the first hardline Muslim group to sweep through the region and I don’t think that it will be the last, but it could be the last that has Sykes-Picot at the heart of the matter.

If we can admit that we made a mistake 100 years ago and perhaps listen to and correct the grievances that we caused, maybe the next wave of violence from the Middle East will just be some guy who wants to make himself king and tyrant and not a group that is a symptom of our own greed and ignorance.