The hijab, niqab, abaya, and other methods of veiling have become extremely politicized and have caused new implications to be associated with them, ones that are rooted in a type of desired and imposed unified singularity. This involves not just veiling, but in how the veiling is done. There are significant nuances in veiling, such as what type of veiling, how much hair is covered, etc. and each has a different connotation which has changed with time. In addition to this, the politicization of such practices have taken away from the religious significance of the act, and they have invalidated those who don’t strictly adhere to what the enforcers deem as acceptable. For the purposes of this article, I will include pictures of the different types of veiling I have mentioned:

Abaya:

Niqab:

Burqa:

Before the Islamist movements of the 70s and 80s in countries like Pakistan, Egypt, etc., the common citizens of these nations were practicing Muslims in every sense. They prayed namaz, read Quran, observed religious traditions and holidays such as fasting during Ramzan and celebrating Eid. In countries like Pakistan, however, where the hijab was not a cultural practice, many women only wore hijab when they were reading the Quran, praying namaz, or when they entered the masjid (and in countries such as Pakistan, women do not even enter the masjid). Otherwise, they remained unveiled, or they would loosely wear a dupatta over their heads when going out, or in front of men who were not mehram (men who weren’t related by blood or by marriage).

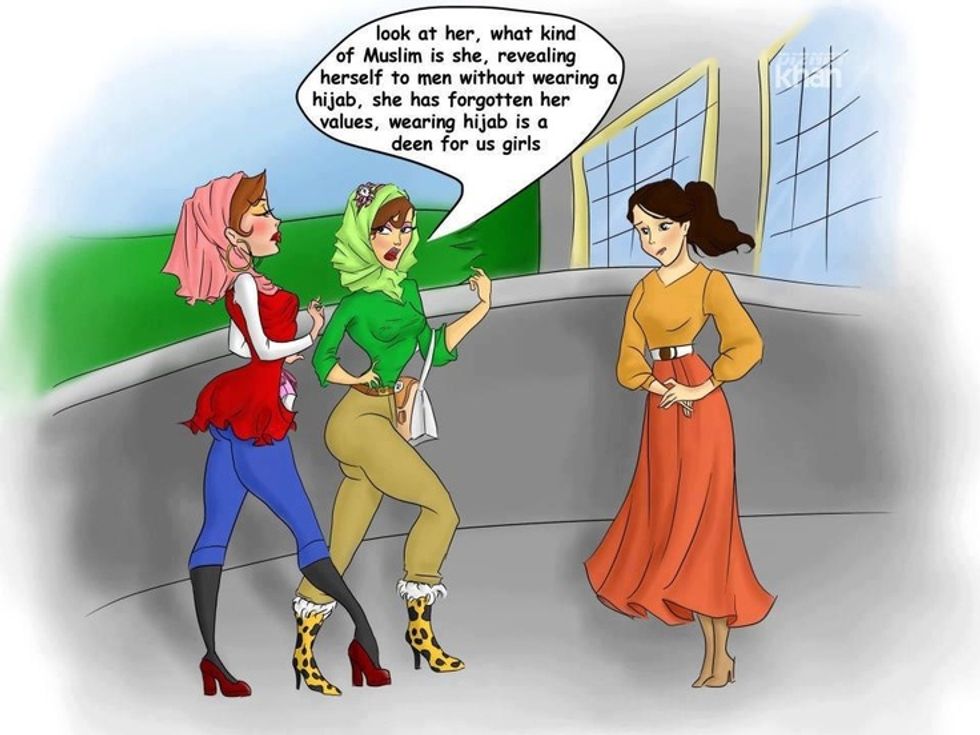

The problems started with the Islamisation when Zia ul-Haq came into power. Zia ul-Haq was a general who became the sixth president of Pakistan in 1978, who held power until his assassination in 1988. His ideology was aligned with the Wahhabist practices of Saudi Arabia, which required not just veiling, but a specific type: The niqab or abaya. More specifically, the Arab way was the only “correct” and acceptable way of practicing Islam. In essence, praying namaz and dressing modestly in shalwar kameez or sari (which became labeled as a “Hindu” dress and therefore immodest and improper) was no longer enough to be considered devout and practicing or even accepted by society as a Muslim. In fact, to be practicing in any other way would make you seen as a munafiq (hypocrite). Other fanatical religious leaders such as Farhat Hashmi continued the trend in the 90s and asserted that a true Muslim women must wear the hijab (or some type of veil full-time). This idea can be seen in pictures of the women in Jamat-e-Islami and ISIS (below), who all adopted identical niqabs, showing a sort of solidarity and showing that single accepted way of dressing for women.

When it came to external practices in regards to physical appearance, the hijab, burqa, niqab, and abaya became mainstream. It wasn’t just enough for a woman to cover her hair, she had to do so with a particular style of covering. It invalidates all other methods, such as the tribal and traditional head coverings and also traditional clothes worn by Muslim women in Africa, and the dupatta, shalwar kameez, and sari used by Muslim women in Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh. All of these women would dress conservatively in their own cultural attire, but with the Islamisation of these nations it suddenly became invalid and a woman’s religiosity and haya (modesty) would come into question.

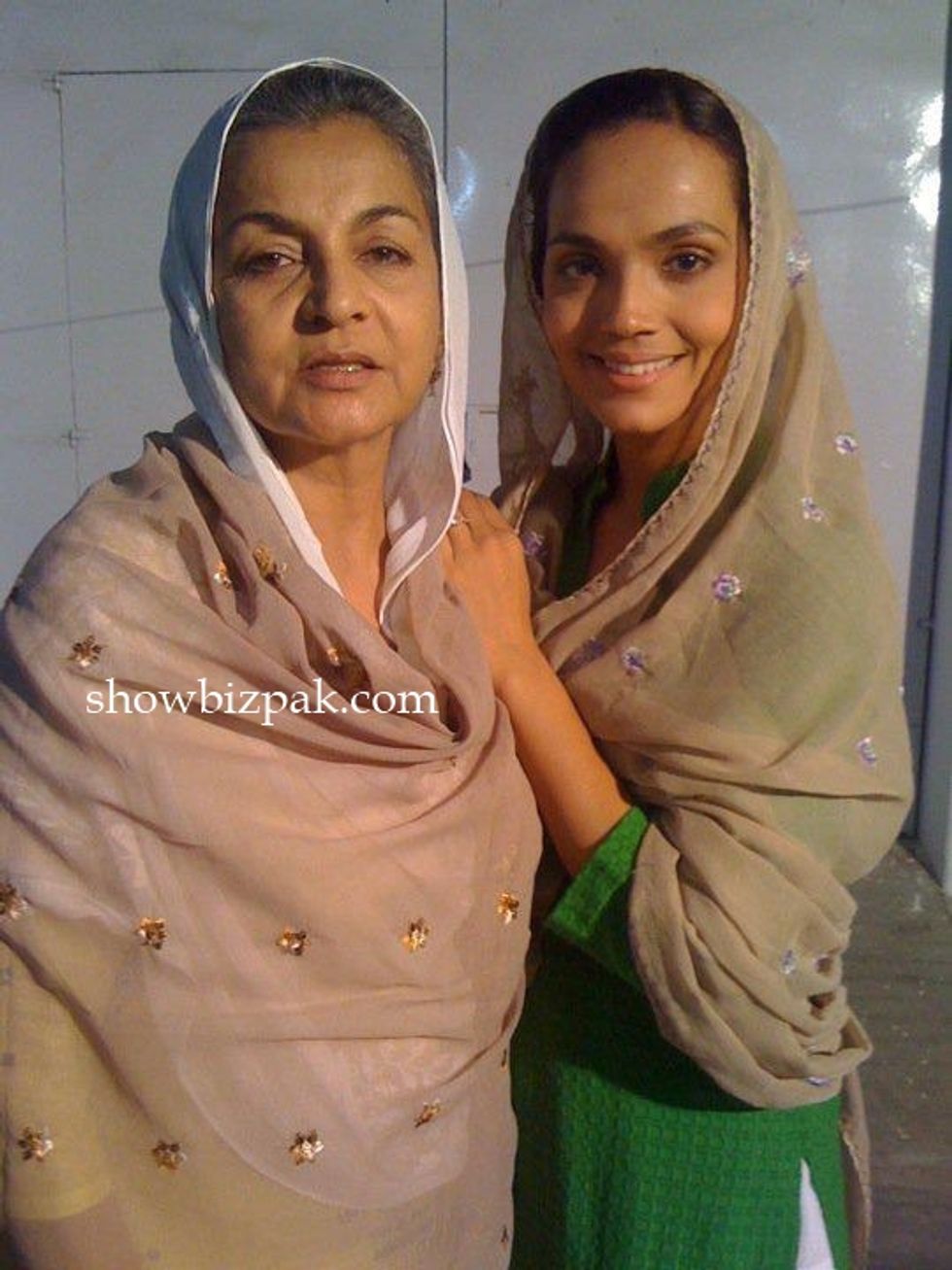

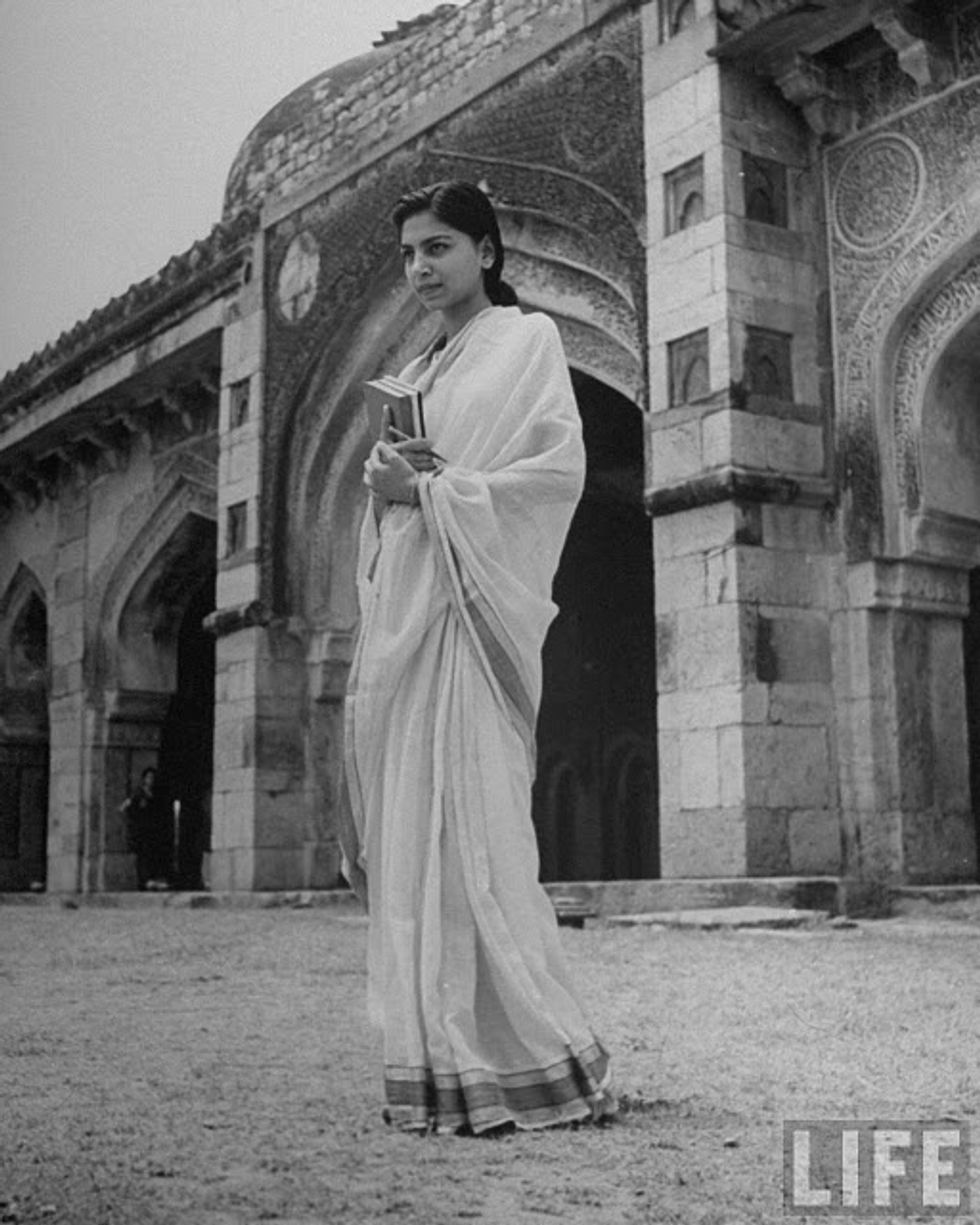

Here is an example of the dupatta (scarf) worn loosely around the head in Pakistan and India, with some hair showing, which is still how many women cover their hair today, and how most did before Islamisation (before this became invalidated by Islamisation, and then full covering was the only way to be seen as practicing):

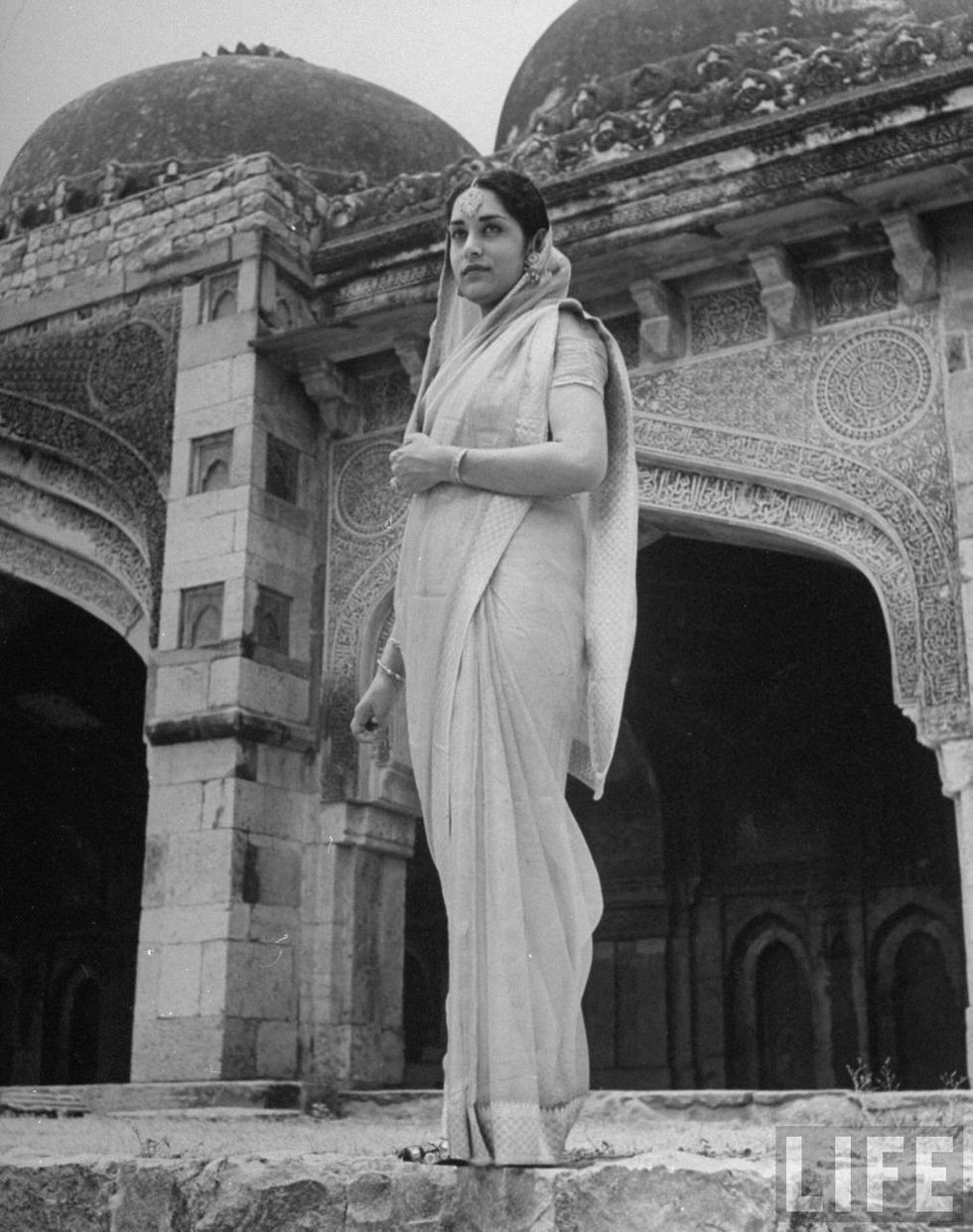

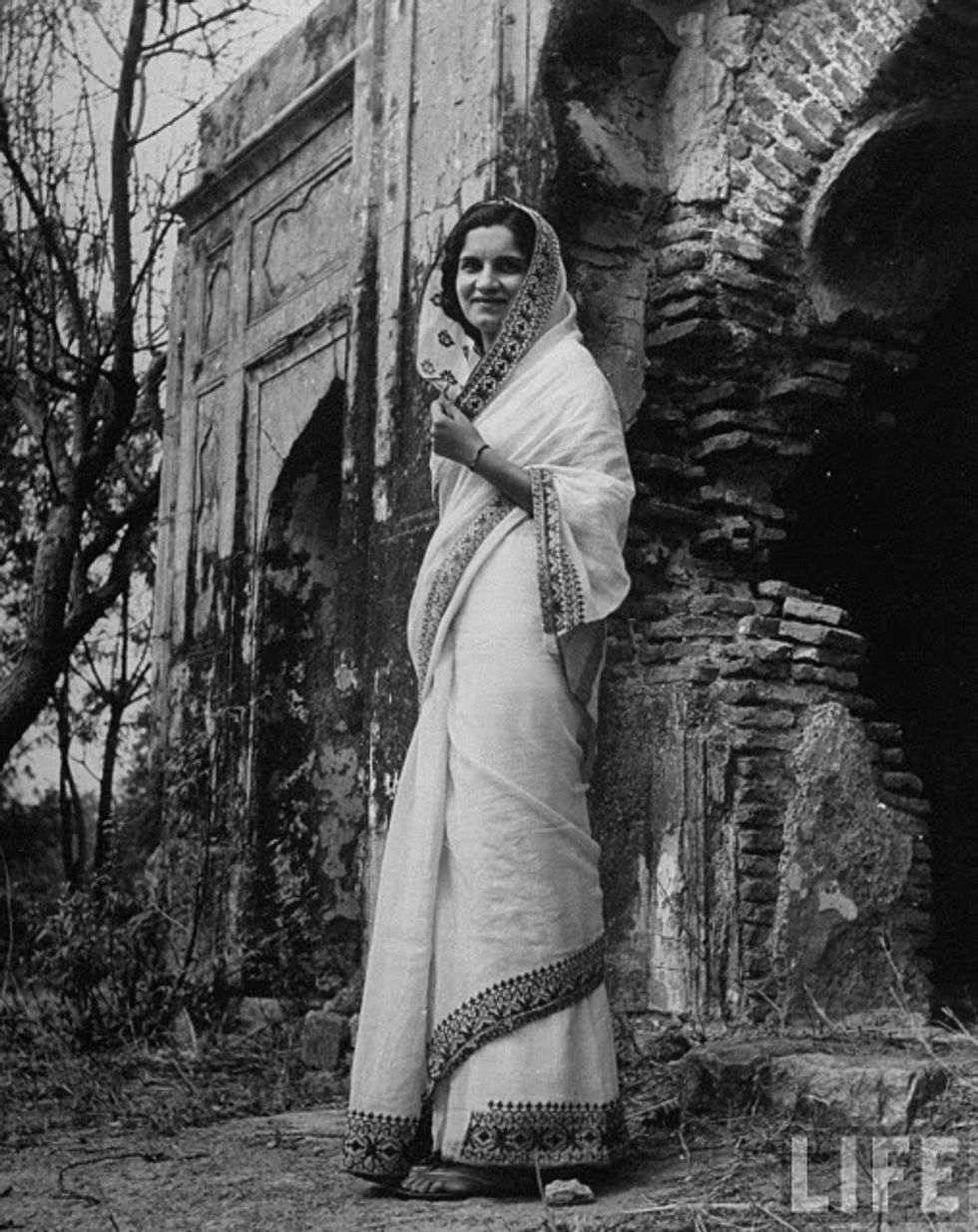

Muslim village woman in a sari, loosely covering her head:

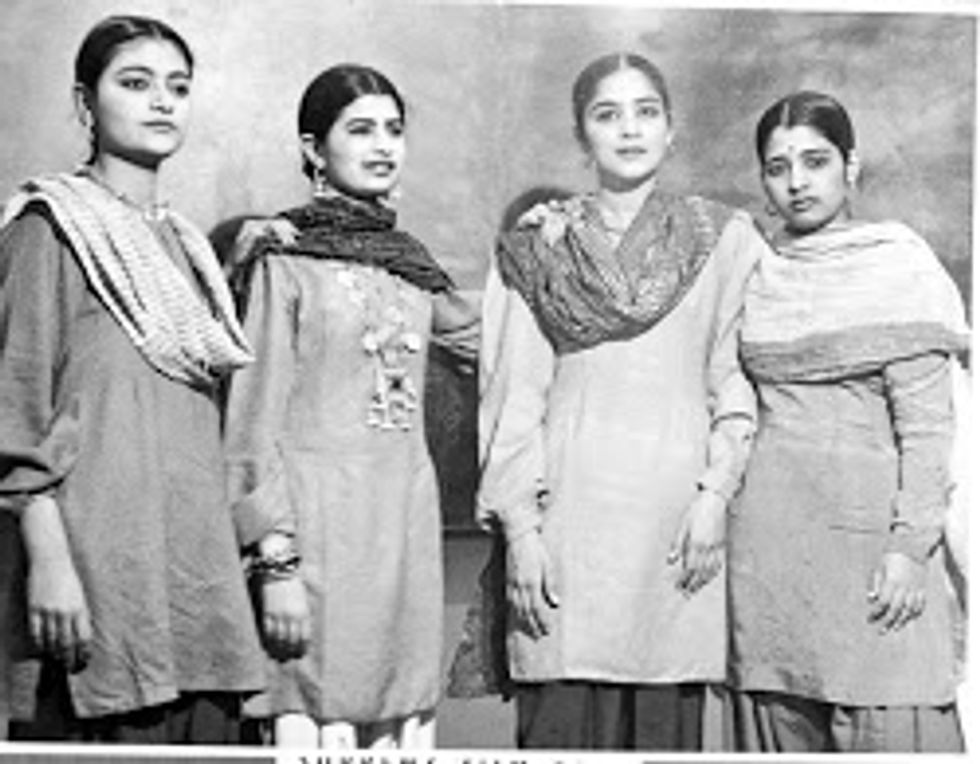

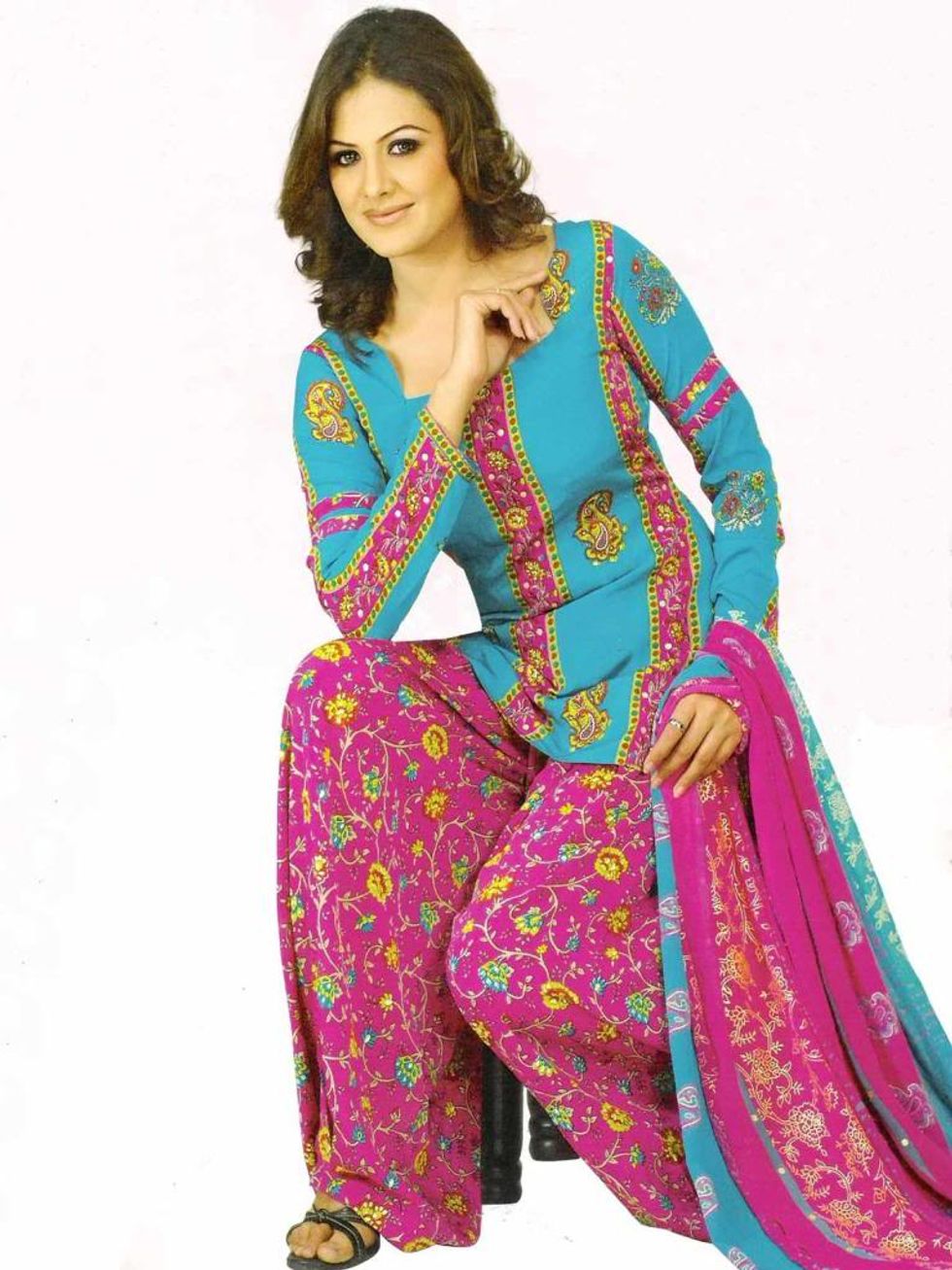

Here are images of Pakistani and Indian Muslim women in shalwar kameezes and saris before Islamisation:

Interestingly, a similar phenomenon is happening today with Muslim women in the United States. Just like the Islamisation of Muslim countries back in the 70s, making promoting a singular “Arab” style, Muslims in the United States and other western nations are promoting a singular and narrow image of what a Muslim is. And just like how the new “Arab” style in such nations was promoted and people dressing in traditional clothes was condemned for being “shameful” and “munafiqs”, Muslims in western nations have developed their own representation which is just as oppressive and hypocritical. The only difference here is that in their eyes, those Muslims who deviate from this style are not non-religious, but instead too religious and too cultural, too imbalanced. They make themselves stand out more than they have to. Muslim American activists such as Dalia Mogahed, Linda Sarsour, and countless others are all hijabis, have become the face for “practicing” and “moderate” Muslims, projecting themselves as the ideal Muslims. In fact, the image of the Muslim woman with an American flag as her hijab on the poster for the Democratic Party was synonymous with the images and physical representation of people like Linda Sarsour and Dalia Mogahed. It boils down the image of not just a desirable and “good” Muslim, but also the image of a practicing one (American or not), to a hijabi. And notice that such figures (even the men such as Nouman Ali Khan) incorporate assimilation into their external representation. They’re all wearing the same style of hijab, and wearing modest western clothes. This gives the implication that the Muslim who wears a sari or shalwar kameez, or even a niqab, abaya, or burqa and speaks in other languages in addition to English, is out of the norm from the “good” and moderate Muslims, indicating that wearing a singular type of hijab and western clothes and speaking only English is the most desirable physical representation. It is the least threatening and most assimilated. Muslims who choose to dress in cultural clothing or cover their head differently and speak in a language other than English are archaic and backwards because it shows a lack of assimilation. In the eyes of both the media and certain members of the Muslim community, these Muslims are the ones who are likely to veer towards extremism.

Women in hijab wearing western clothing:

Poster for the Democratic Party for “Muslim” representation:

It is women like this who have become the face for practicing and devout Muslims, who are not extremists. Much to my resentment, this is promoted by both the western media, and members of the American Muslim community. They retain their “symbol” of a practicing Muslim while conforming to western culture.

Meanwhile, in the western world these types of Muslims who wear hijab but non-western clothing would be considered practicing by non-Muslims, but as archaic and backwards by members within their Muslim community who promote assimilation and conformity to western norms (this also includes women who do niqab, burqa, and abaya):

Hijabi women in shalwar kameez and sari:

There is an additional problem to this symbol of Muslims for the western world: It implies that the only representation of a practicing Muslim woman is the one who wears hijab or covers her head. People like Dalia Mogahed have only to wear the hijab to prove their spirituality and their beliefs, whether they privately practice or not (I do not presume to know the personal practices of Dalia Mogahed, Linda Sarsour, or any other Muslim leader; I am simply pointing out that to the world they have only to wear the hijab to prove their devotion and come off as practicing Muslims). The implications of this are that a hijabi Muslim woman could be completely non-practicing, in the sense that she doesn’t pray namaz, doesn’t fast during Ramzan, perhaps even consumes pork or alcohol, or even dates, but because she wears the hijab she is the trademark of what a practicing Muslim is. Meanwhile, a Muslim woman such as myself wearing a sari or shalwar kameez who does pray namaaz, reads Quran, and observes religious practices (much like the women in Pakistan and India did before the Islamisation) would be dismissed by both the Muslim community and the western world as a non-practicing Muslim, one only in name. This type of Muslim would be seen as calling themselves Muslim for the sole purpose of showing solidarity with the community and not actually practicing. This speaks to the politicization of the singular type of hijab in the western world (and also the niqab, abaya, and burqa in many non-Arab Muslim countries, who wish to promote unity in a singular form). In both cases, wearing them has become less about spirituality and more about making a statement.

In essence, in the western world these type of Muslim women (shown below) who do practice the tenets of Islam would not be considered as practicing by neither members of the American Muslim community who wish to promote integration and assimilation, nor would they be considered practicing by the non-Muslim community because it doesn’t fit with the singular image of a devout Muslim that they’ve been exposed to through media (Meanwhile, thanks to Islamisation in many Muslim countries, these women below would be seen as non-practicing because even though they are dressed modestly in their own cultural attire, they have not covered their heads):

But in the western world, even though this type of woman (below) would be considered practicing by both Muslims and non-Muslims, they don’t fit the image of an assimilated and integrated Muslim, so members of the Muslim community who want to promote those who blend in would consider such Muslims as primitive, and perhaps discourage them from being promoted as “American” Muslims.

It must also be noted that within the Arab nations, veiling (whether it be with a hijab, abaya, or niqab) has been done for centuries. It is just as much a part of their culture as it is their religion, if not more, similar to how wearing a shalwar kameez or sari is a cultural dress for South Asian women. It is a rite of passage for the women, and wearing it holds less of a religious significance and more of a cultural one. In such societies, the maverick is the woman who does not cover her head. It is for this reason that there have been instances of non-hijabi Muslims from other Muslim nations who are taken aback to see certain populations of Arab hijabis who date, don’t pray namaz, or really practice in any other way except wear the hijab.

The phenomenon of Islamisation did not just affect Muslim nations, but also nations with significant Muslim populations. Muslims in India, for example, constitute over 14% of the population as of 2011, and have had a significant cultural and historical influence within the nation. But just like the metamorphosis that Pakistan had with leaders like Zia ul-Haq, the Muslims of India had a similar transformation on smaller scale long after, perhaps closer to the 90s and 2000s. Both before and after the partition of India, in physical appearance Muslims and Hindus were not all that different, except for the Hindus wearing their bindis and sindoor, and Muslims wearing their tawiz. Muslim men sometimes kept the long beard, but many didn’t, and Muslim women wore saris and shalwar kameezes, much like the Hindu women. These Muslims were still practicing, but they retained their Indian cultural practices. However, in recent years there has been a shift to more “Arab” Muslim practices, much like the Islamisation of Pakistan. There are groups within the Muslim community who aim to differentiate themselves further from their Hindu brethren, which is why it has become more commonplace to see Muslim women wearing hijabs, abayas, and burqas, as means of expressing identity and distancing themselves from cultural practices and Hindus. Even the film industry has changed its representation. As recently as the 90s, Muslims were shown in Bollywood as no different from Hindus, except for their Muslim name and perhaps they would be shown praying namaz, or going to a dargah, or wearing a tawiz (an amulet with verses of the Quran inside it). More recently, however, in films such as PK and OMG: Oh My God, they have been represented as niqabis and hijabis, as ways of singling them out as unmistakably Muslim.

There are two main reasons for this: One, the Muslim minority in India, feeling insecure about their identity and feel even more pressured to preserve their religious identity and practices and stick together in a Hindu-majority nation. One might ask why this has become an issue now, and most likely it would be because of the rhetoric from Saudi Arabia and other nations that underwent Islamisation. They don’t want to be criticized or seen as munafiqs. The other reason is that over the past few years, the Hindutva (Hindu nationalism) movement has gained much more momentum. The oppressive nature of Hindu nationalist parties can ostracize them from interacting with Hindus and push them more and more away from their culture because they are treated as enemies and outsiders. In a Hindu-majority nation, the best way to identify yourself externally as Muslim is to wear hijab or some type of veiling. This relates back to the Muslims in the western world who have taken up the hijab as a means of identifying themselves as Muslim, and for political reasons either instead of or in addition to spiritual ones.

Let me be very clear: I have nothing but utmost respect for my hijabi and niqabi sisters. In a time when the practicing of our faith is most scrutinized and when many around us, for the interest of our own safety and well-being, over-encourage assimilation (a word I now loathe), it is a great act of courage to be able to openly display your religious affiliation. What I resent, however, is the concept that this particular external display of faith has become the only symbol of a practicing and faithful Muslim, and that in today's politically and socially charged climate, the practice of hijab, abaya, burqa, niqab, and other veiling has become more about displaying faith (politically) and solidarity (which isn't a bad thing) than its true purpose: Modesty, chastity, and virtue. I have experienced first hand the dismissive and judgemental nature of such people: In the west, I don’t fit with the media or even the American Muslim community’s version of a practicing Muslim because I wear shalwar kameez on a daily basis and because I don’t do hijab, even though I observe all other religious practices (including modesty and refraining from practices such as dating, drinking, etc.), and do cover my head in the masjid, when I pray namaaz, and when I read Quran. And in the South Asian subcontinent, while I might still be accepted as a practicing Muslim, I may still be looked down upon for not adopting the unified “Arab” style clothing that many conservative and orthodox women now down. In essence, one might say I belong back in Pakistan before Islamisation!

There is no doubt that the meaning of veiling and its methods have undergone a troubling transformation over time. Along with the politicization of veiling has also come a loss of spiritual significance, as can be seen with the rising trend of “part-time hijabis”, who wear the hijab only at certain times and place (the latest of this being non-Muslims and non-hijabi Muslims wearing the hijab to political rallies to show solidarity, and taking them off afterwards, again taking away from the spiritual significance). This is problematic because as admirable the gesture is, it does trivialize the meaning of hijab and veiling in general: At the end of the day, they can take it off and go back to “fitting in”. But there is a religious and spiritual significance to it that cannot be turned on and off as one pleases. For non-Muslims, this also gives in to the narrative that the only types of practicing Muslims are hijabis, so they can only show solidarity by wearing hijab. For non-hijabi Muslims who practice who are taking up the “part-time hijabi” trend, they feel that the only way they can fit in with the image of a practicing Muslim is by wearing the hijab, because that is the most promoted image of a Muslim within the western world, so they cannot feel comfortable representing their faith as they are.

In the Muslim world, while perhaps the Islamisation of Muslim nations was intended as a means of solidarity and unification, it has proven to be exclusionary and isolating. What such nations and their leaders fail to remember is that the Quran has rules and guidelines for dressing modestly, but there are no specifics as to what and how to wear the dresses. This is why for so long the people of such Muslim nations were complying with the tenets of their faith, each in their own way. But due to Islamisation, these nations were brainwashed into believing that the Arab way of external representation and practice was the “true” and “correct” way, and that they must “civilize” themselves and return to the correct path. This reverence is similar to the countless colonized nations today what still worship and follow the practices and culture of the western nations who colonized them in the first place, still thinking themselves inferior to them. Shoving all Muslims under a singular and somehow superior representation of Islam is one of the reasons there is so much conflict and animosity today, especially amongst Muslims themselves. The fact of the matter is that this is a religion with followers from dozens of different countries, each with their own way of representing themselves. No one way is more correct than another, contrary to what Saudi Arabia and other Arab nations would have us believe. It is important to raise awareness of the different types of Muslims, from all over the world, and show them all as valid and integral parts of the community. For the sake of the religion and its followers, we cannot allow such biases and exclusions to continue to take away the identities and spirituality of the adherents of the faith from all over.