“Why do Fireflies die off so young?” If you ask a Ghibli fan which of this Japanese animation studio’s movies was the most tear-jerking, then their answer might very well be Grave of the Fireflies.

This Isao Takahata-produced film opens on September 21, 1945 shortly after the end of World War II at a train station where our 14-yr old protagonist, Seita, is dying of starvation. The candy tin beside him is thrown by a janitor and from it, spills the spirit of Seita’s younger sister, Setsuko. Their spirits then join hands in a cloud of fireflies. The audience knows the film is going to be sad from beginning to end.

At its front, this appears to be an anti-war film. It shows the struggles of two children following fire-bombing of Kobe. After the death of their mother (and the supposed death of their father in the war), Seita and Setsuko must survive on their own. As the film progresses, Setsuko eventually gets sick from malnutrition, and dies right before Seita returns to bring her medicine. This leaves Seita alone to drag himself into the city and die, which you witness at the beginning.

I think that rather than scorning the consequences of war, this film better illustrates a sense of de-masculinization. For the Japanese, there are two distinct narratives regarding their participation and defeat in World War II, as well as the American Occupation. The first opinion is that the West was wrong and had no business occupying Japan. Japan used to have pride before the war and losing it stripped away all sense of that. This sort of outlook is fortunately shared by very few right-wing extremists. The majority of Japan’s population accepts the theory given to them by the West. That is, Japan was being ruled by an evil government and therefore Japan’s people were consequently victims of the war. America saved Japan by removing its old leaders and building a more modern, Western civilization up from the ashes of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

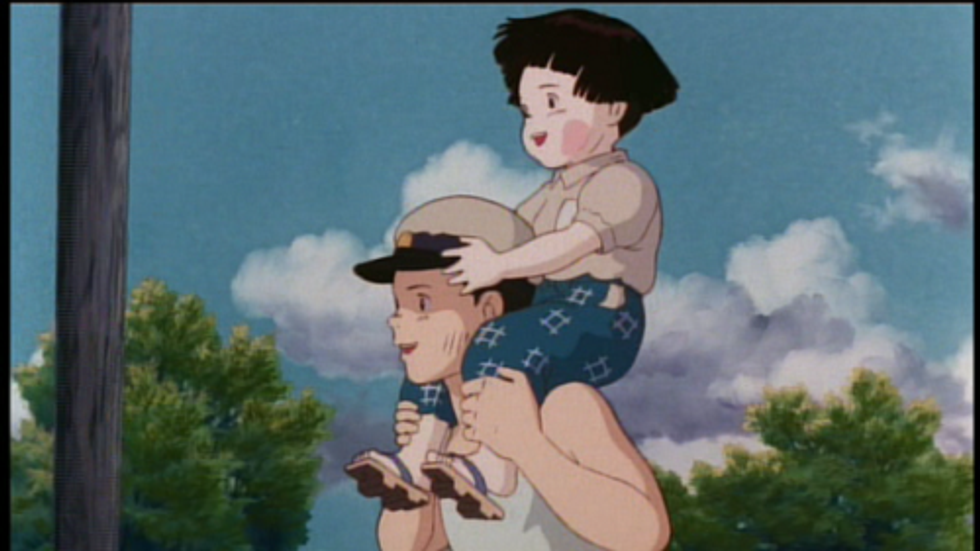

In Grave of the Fireflies, there is no sign of anti-war messages. After all, Seita’s father is in the Japanese Navy, a fact that the boy repeatedly praises. The stronger sense I get from watching this, is the de-masculinization and victimization of Japan through Seita. As the older brother and the man-of-the-house while his father is away, Seita is entrusted to nurture and protect his sister, Setsuko. He provides for her and carries her everywhere. Gradually, his sense of pride and masculinity is peeled away.

For example, we witness him trying to steal food from a farmer’s yard only to get caught and beat up. Setsuko faithfully waits for him at the police station until he’s released. Upon seeing her, Seita cries and hugs her. The roles become reversed and it is the younger child comforting the older. Seita is reduced to a weak, little boy who cannot even save his sister from dying.

Therefore, I interpret Seita’s failures as Japan being no longer able to take care of itself. Japan needed someone’s help to recover. The Japanese soldiers would courageously fight but the citizens were the victims of the war they were told they’d win. If viewed this way, I think the film caters strongly to neither right nor left wing narratives. It shows both a loss of pride from justified actions, but also the helplessness of those lost behind.