Dear World: when you picture a writer, what do you see?

Last week, I wrote that English students still had a place in this world. We're important, I said, and our job is especially valuable in a world where the cultures with which we interact are so often reduced to pictures on the internet and talking points on the news.

Sometimes, though, it's hard to believe that.

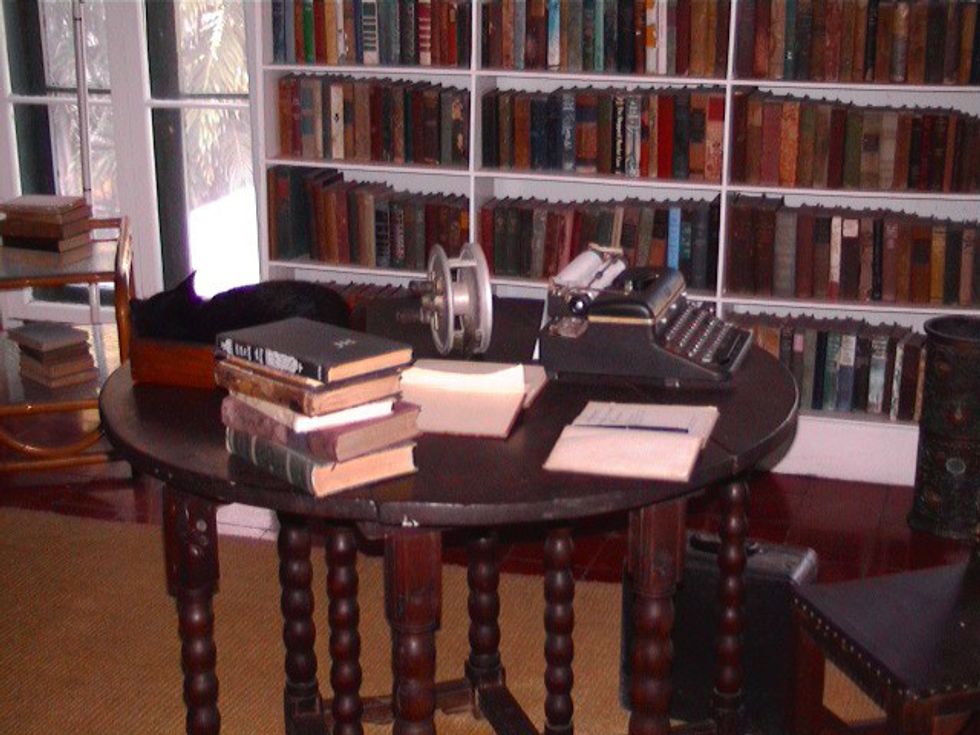

Readers and writers have a reputation. Sure, we're interesting, but we're also dusty. We like dusty old libraries with shelves no one could ever reach without a crane. We like dusty books with gold designs pressed into the spines. We like dusty, solid mahogany desks for writing dusty-sounding poetry and prose. Not only do we know how to use "thee" and "thou," we also believe everyone else should know. We may even use those words in text messages--I know I do.

I can't deny it. We do love our dusty old rooms and books. The tales they tell are what brought us to where we are, and we can never be thankful enough for that.

That being said, though, the literary world isn't sequestered away in antiquity. We're actually adjusting quite well in the Internet Age. Let's talk for a moment about poems. When my roommate thinks about poetry, she thinks of old epics. When my friend on the second floor thinks about poetry, she remembers villanelles and Petrarchan sonnets. Yes, we study these, and yes, they are certainly good poetry, but the poetic world is growing beyond them, I think, and it's becoming too broad for any one person to study or watch.

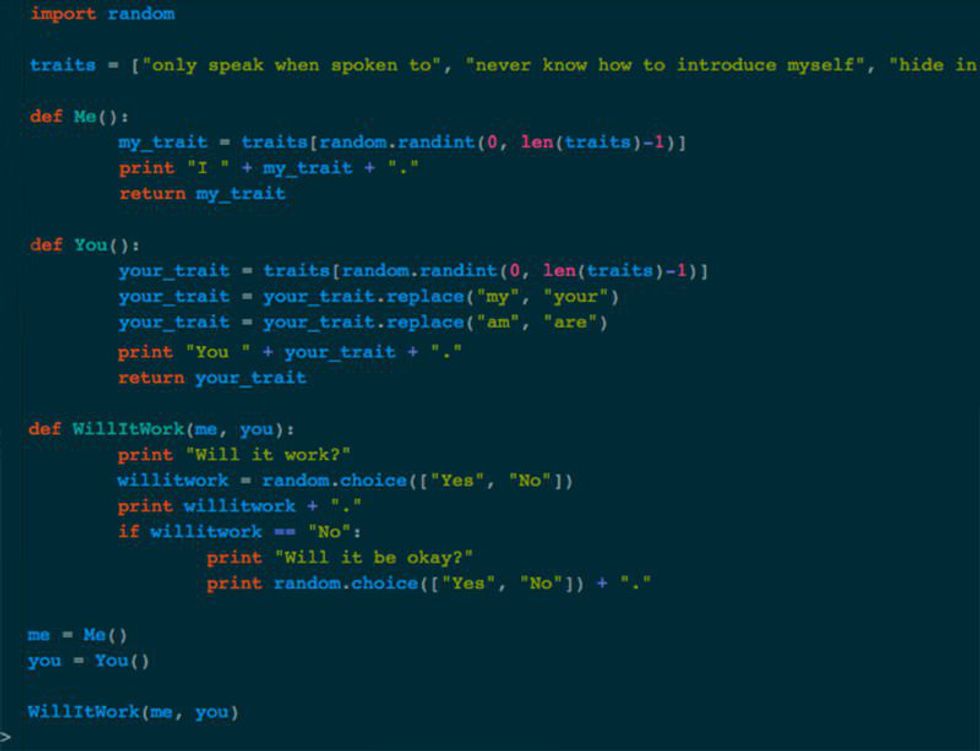

People have written poems in computer code. People have taken the dusty forefathers of literature and reinvented them with techniques like erasure, using them to address new ways of thinking. Poetry is now, as it always has been, an effective way of addressing current events, which certainly aren't irrelevant or forgotten. Take a look around, and you'll see that it certainly isn't limited to love and flower gardens and long-winded heroes, and the formal rhyme and meter of the past are largely kept in the past – actually, many journals specifically request that writers not submit rhyming poetry, and many promise to reject "light" verse.

Fiction has changed, too. Storytellers have changed their language to communicate with internet culture, with math and with science. As the world has sped up, a new genre has emerged, called flash fiction, which condenses the story to a thousand words or so. Some take it further—Prime Number, a reputable online magazine, judges a 53-word story contest every month. Informally, Facebook is home to such ideas as the Six Word Story, followed by over a million people. Writers experiment with time, with fluid identities, and with ambiguous endings, which rose to attention in the 20th century. Many say that fiction has kept more of its original traits than fiction—everyone loves a good storyteller, it's true—but it, too, has changed and grown to reflect the world in which its readers live.

Yes, I study dusty old books for class, and yes, I love my dark, heavy wooden writing desk on the top floor of the library, but that doesn't mean that my world is frozen in years gone by. I don't write in Old English. Most other contemporary writers don't, either. We write instead in a language that answers Old English, and we write about unstable meanings, about the leap between nature and humanity, and about learning to read identity in different ways. We do our best to crystallize these things as they arrive, to make them tangible.

This current version of the world shapes our thoughts, so it shows through every line and sentence we write. Please, if you think poets and storytellers have become irrelevant, think again. We're writing about you.

This article is the second of a series called Letters From An English Major. Please stick around for the next one!