On December 12, 1985 the Supreme Court began hearing oral arguments for Batson .v. Kentucky.

Peremptory Challenge: a defendant’s or lawyer’s objection to a proposed juror, made without needing to give a reason.

On one side were the attorneys for James Batson, an African American man who had been convicted for burglary and receipt of stolen property, claimed that the prosecutor in his case had used their peremptory challenges to excuse black jurors simply because they were black.

SCOTUS ruled on April 30, 1986 that dismissing jurors because of their race is unconstitutional and that doing so violates the fourteenth amendment’s “Equal Protection” clause. Simple enough, right?

Twenty minutes ago, I ended a conference call with three Franklin County, Ohio attorneys who laid out just why the ruling is all bark and no bite.

Here’s an example of how a Batson Challenge may be used:

An African American is on trial in a county with a very minority population. If there are no African Americans called for jury duty, a Batson Challenge may not be called. Why?

First, since no members of the defendant’s race were called to serve, a Batson Challenge would not apply. Batson .v. Kentucky covers only peremptory challenges, not the jury pool. The defense attorney (or prosecution if he/she is a really good guy/lady) would need to take issue with the jury pool not being diverse. Juries are required to be representative of the community even though sometimes, the community isn’t representative of the defendant. The An all white jury for an almost/all white community is considered reasonable.

Now, let’s say that one of the few minorities in this community are called for jury duty and they are dismissed using a peremptory challenge. If the defense believes that the prosecution dismissed this juror because they are a member of the defendant’s race, they can cite Batson .v. Kentucky.

The prosecution is now legally obligated to give a reason as to why the juror was excused. The court is extremely lenient with what can be considered an acceptable answer. Basically, as long as the prosecution doesn’t say “because he/she was black” and barring any physical proof (ex: marking “B” next to the juror’s name) the prosecution has just successfully defended themselves against a Batson Challenge.

Out of countless examples of how a Batson Challenge may be defended, one of the lawyers previously mentioned above shared a personal experience.

“He (the prosecutor) said that the juror, who was black, didn’t look like he was paying attention.”

When writing articles, I tend to think about how the situation at hand would affect me. This one was no different. I am biracial (half white and half black) so what about me? I asked the attorneys. Their answer? I’m SOL. One shared that they have had this issue. She cited Batson .v. Kentucky when the prosecutor had dismissed the last black juror from the pool. She claimed that the prosecutor defended his choice by saying:

“The defendant is biracial, there are members of his race on this jury”

Like I said, SOL. She then says she responded by claiming that a jury wouldn’t know that the defendant was biracial and asked that the judge take into account that the police didn’t. He was booked into jail as “African American” not “biracial” and was described in police reports as an “African American Male” — not a “biracial male”.

If law enforcement didn’t know, how would the jury? At this point, rather than engage in a battle of “is the defendant dark enough to be considered black or light enough to be considered white” the judge overruled the challenge.

After thinking about how situations would effect me, I get to thinking about how they would affect others. I then had another thought.

“Is there anything protecting women and LGBT people?”

Their answer, once again, was a unanimous no.

Lawyers aren’t even allowed to ask a person’s gender or sexual orientation during jury selection. They can only ask if they “know someone who is a woman or member of the LGBT community” if the juror chooses to say no, that’s the end of it. There is no legal way to assure that there will be a fair jury when it comes to Women/LGBT individuals. As we know, the batson challenge only covers race.

Not being allowed to ask a person’s sexual orientation or gender is supposed to discourage discrimination but in turn, enables it. This is a theme shared with the Batson Challenge.

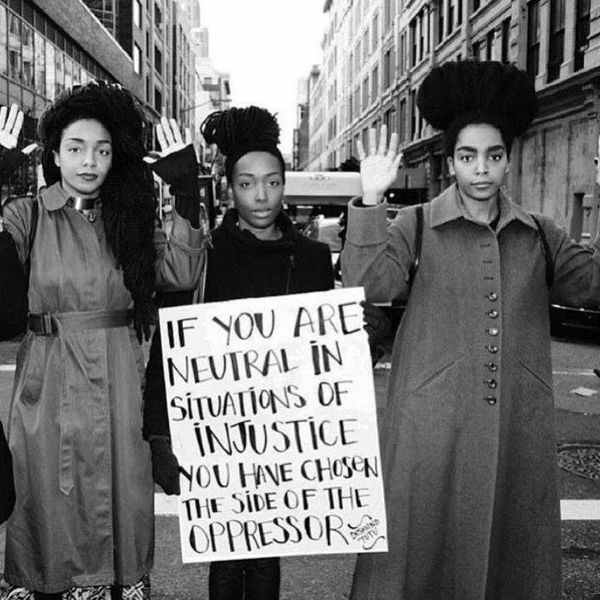

In a country where equality is at the forefront of most conversations, is it time to acknowledge that the band-aid we’ve placed on a gaping wound is not working? Shouldn’t we address it now to prevent further infection? In the process of jury selection, nobody is off limits to discrimination. Your fate is, in part, left up to demographics. It’s time to implement some safeguards. In this instance, Lady Justice need not be so blind.