John L. Parker, Jr. has a habit of grasping the attention of generations of endurance athletes to come, encapsulating the joys and stages of suffering of a sport in a single piece of literature — a rare occasion to precisely relate to something one reads — and then, disappearing. It has been 37 years since the release of his debut novel "Once a Runner." After 30 years passed, filled with several nonfiction works including Parker's commentary on the runner lifestyle, before the saga of fictitious miler, Quenton Cassidy, resumed in "Again to Carthage." Though fans were satisfied with the continuation, something still remained incomplete in the series. "Racing the Rain," released this past summer, completed Parker's insightful legend he set out for himself to fulfill.

We witnessed Cassidy run a sub-four minute mile from the bleachers of the pages of "Once a Runner." The turning pages setting the pace of the race, substituting for the distance markers of each lap and every passing second winding down the stopwatch. He was only a college kid. He wanted to yield a product that he knew would be the supreme testament of what he was capable of. He put his happiness aside to do what he loved, asserted by his commitment to grueling workouts.

He ran. He ran when it rained, did 20 mile days when it poured. His feet hurt, his feet shot with pain, his feet bled. He trusted himself, more importantly he trusted his body — his ultimate weapon — especially when 15 miles worth of 400 meter repeats forced him to fall into a subconscious rhythm. He gave into the madness of materializing duly-recognized accomplishment.

In "Again to Carthage," we were with Cassidy when he completed one of the greatest physical achievements designed by man: the marathon. No shocker that he qualified for yet another United States Olympic team. He was a man, a full-grown, responsible adult. He sought to give it one last go at something big — bigger than himself — to know it could be done, by him.

He ran, ran more than he thought possible. He ran more than he wanted. He ran more than most people run in a lifetime. He was fine where he was, he just needed to know something if this magnitude could be done to put his unnerved skeletons to rest. He reawakened a madness within. But it subsided. He finally learned to be satisfied; a demon that may rage for an entire lifetime when possessing athletes.

Parker penned one of the greatest novellas known to anyone who laces up their running shoes, goes out the door, tests their limits and willfully calls him/herself a runner. He met the requirement of the story-writing cycle by authoring a convincing "after." Acclaim turned to calls for the cycle to spin the other way. Loyal fans wanted a "before." Not even a perfect "before" but just something, a table scrap, that provides readers a clue as to how Quenton Cassidy dove head first into the daring pursuit of individuals brave enough to plunge into a painful, oval-shaped gauntlet. We wanted to learn why Cassidy poured blood, sweat and tears into running, and why competitors would have to do the same if they wanted a shot at him.

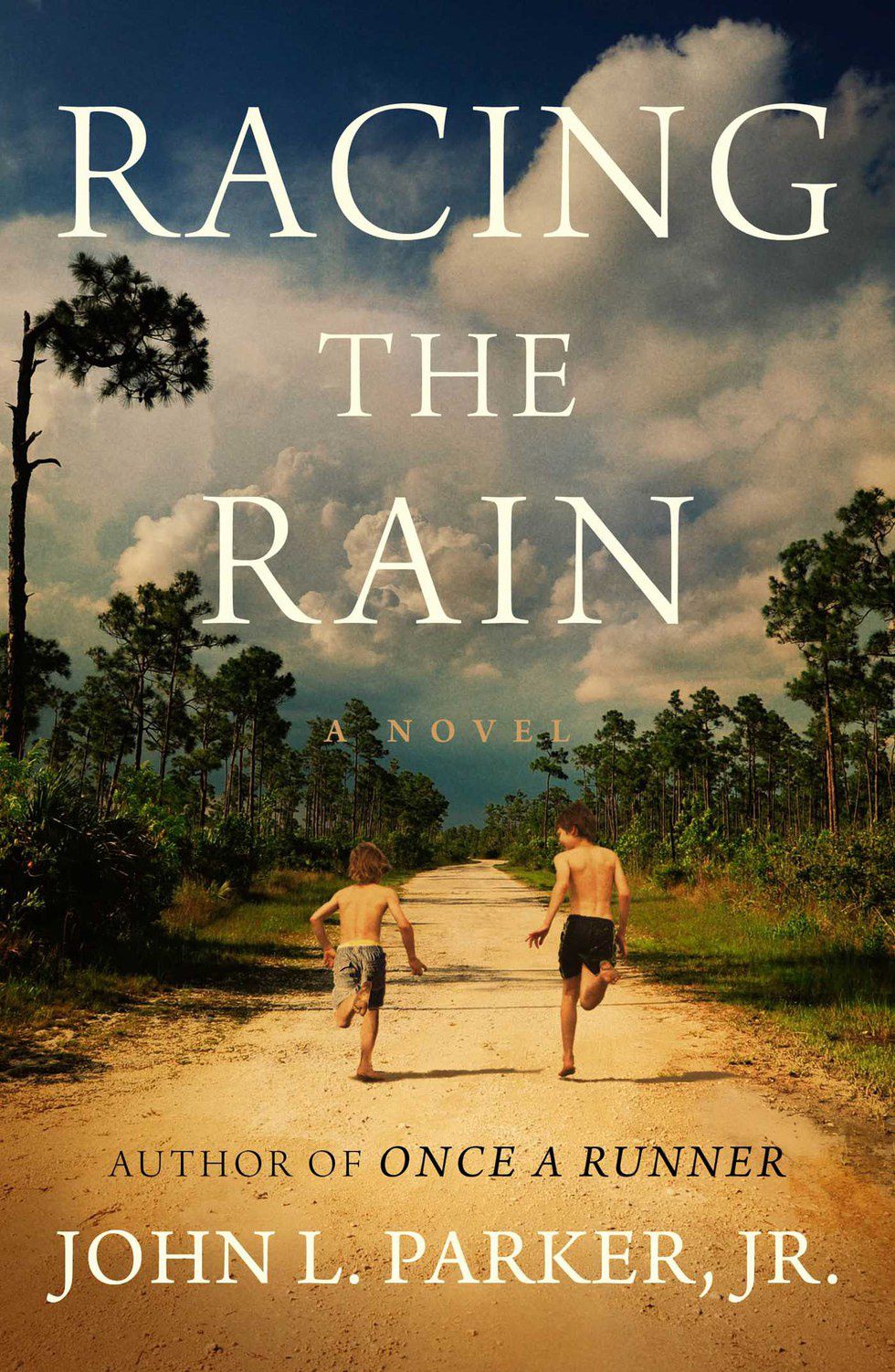

"Racing the Rain" provides that introspection into young Quenton's youth and how he was converted into a runner.

Quenton Cassidy grew up in typical Smalltown, America, located in Florida's Gold Coast. His father worked as an engineer at the nearby naval base, his mother a quiet housewife. Flashbacks from series predecessors unfold as Cassidy's diving and fishing talents are explored. Locals praise the young protagonist's capability of holding his breath for several minutes when diving down to depths of 40 feet. Even in his teen years, before he became a distance runner, Cassidy's lung capacity is extraordinary.

"Once a Runner" opens up to Cassidy in the midst of being a college runner, a miler running in the nationally ranked lead pack. Cassidy in "Again to Carthage" lives a post-running life. Cassidy in "Racing the Rain" is not even a runner, yet. Brief reminiscences of being a basketball phenom from a small hometown has been brought up. Shooting hoops is a pastime most children partake in. Cassidy's community from the 1950s to early 1960s is no exception.

Origins of Cassidy's ambition derive from having been the runt of his friend group. He is bested regularly on the basketball court as a result of his relatively short stature. Shots swatted down to the pavement. Possessions stolen by well timed slaps. Air balls, gliding into nothing, aplenty. Competitive drive was challenged into a different kind of "Orb" (a chapter title from "Once a Runner," metaphor for Cassidy's process for keeping his emotions together during a race): the bouncing orange spheres, housed in the hard, wooden-floored temples of high school gymnasiums.

Whispers of doubt barrage the aspiring star's daydreams of making it past the high school basketball team's qualifying cuts — the making of the team came later. Cassidy's quasi-Protestant work ethic paved the path to follow to reach success. Frustrated, Cassidy could do things for the satisfaction of proving others wrong. But the countless hours of layups, full court charges, pick-up games with more experienced, bigger, faster Navy personnel were not for them. Visions of grandeur are one thing, but the walls of limitation crack and crumble only when the overwhelming force of concentration is applied against them.

Parker framed the story to be consistent with Cassidy's character. Cassidy did all this, bore the weight of his world on his shoulders, all for himself. From then, he did everything to prove to himself what he could do. Vain stills of raking in the benefits of popularity are occasional, yet Cassidy always found a way to quickly return the glory to someone he thought deserved it more.

Bittersweetly, the majority of the plot is less focused on running obsessions and more on Cassidy's experiences with bizarre goings-on in town. Basketball, like track, is merely the medium plot device that moves Cassidy forward as a character. Parker lightly sprinkles moments of introspection, as he always does, between his pages to unintentionally into Cassidy's actual life. In the technical sequels to "Racing the Rain," running vents feelings of rejection or love lost without Cassidy ever saying words to give such actions meaning out loud.

A moment of family distress is mentioned in one chapter with an implied resolution in later chapters, not a mention of it by Cassidy or him to anyone else. Runners live in the present, a lesson Parker knows all too well; the past chips away at focus and the future is something to be made into a reality. I suppose getting hung up, or having to acknowledge with anyone else, personal tragedies can be the downfall for certain people possessing a certain motivation to keep them moving forward.

At first glance of the junior high track team, running is represented by a band of misfits from all levels of the social food chain coming together, hoping to perform a function for the team in the end. Sure enough, Cassidy joins this rambunctious squad when his attempts at making the basketball team are yet again spurned.

Future Southeastern University teammates Jerry Mizner and Jack Nubbins make cameos as rivals in Cassidy's timid approach to perfecting his personal best in the mile.

Surprisingly, the majority of the story is not spent obsessing over running. In fact, Cassidy only runs four races — two cross country and two track events — and only two of them he was specifically training for in hopes of out-kicking the field.

While the final race in "Once a Runner" lasted the span of one glorious, drawn-out chapter, if not several chapters, "Racing the Rain" keeps coverage of Cassidy's races concise and relatively short. Most chapters are fairly short, summarizing bizarre going-ons in a few pages. The pages do fly by. Still a young boy, I suppose the intensity of Cassidy's training has not reached the level of his future selves.

Though content describing running events is more limited than preceding books, Parker can still evoke that tingly feeling from readers, particularly the runners who know where he is coming from. The training, the racing, the times, the disappointment, the excitement, the overall experience. Parker can amusingly make some angry that they cannot turn back the clock, return to the glory days, get another chance at beating a different clock in their races. I suppose, again, his later books deal with those feelings of lost chances, and that there is always redemption.

"Racing the Rain" reminds readers of the past. Its main asset is the reminiscent factor, bittersweet I know, but amazing to look back at accomplishment. Just like a movie, readers will place themselves in the shoes of Cassidy, be the hero of their timeline as they read the book, becoming the hero. Quenton Cassidy, may be a running god crafted by a talented runner and writer, but he is representative of anyone that goes out and chases "the dream." The dream of glory and greatness, recognition, achievement. Anything that puts us at odds and must rise to the occasion and overcome.

The book is a reminder, not on just running culture, but just anyone discouraged from being the best they can be. At anything. It is a reminder of where the obsession came from. Why we do something. Why we fight to continue doing it. Make it a part of our routine everyday. After putting the book down, closing the last page and in turn the hardback cover, I remembered why I started doing something as insane as running. I remembered why I started doing something I love. And hope to still do it. What about you?