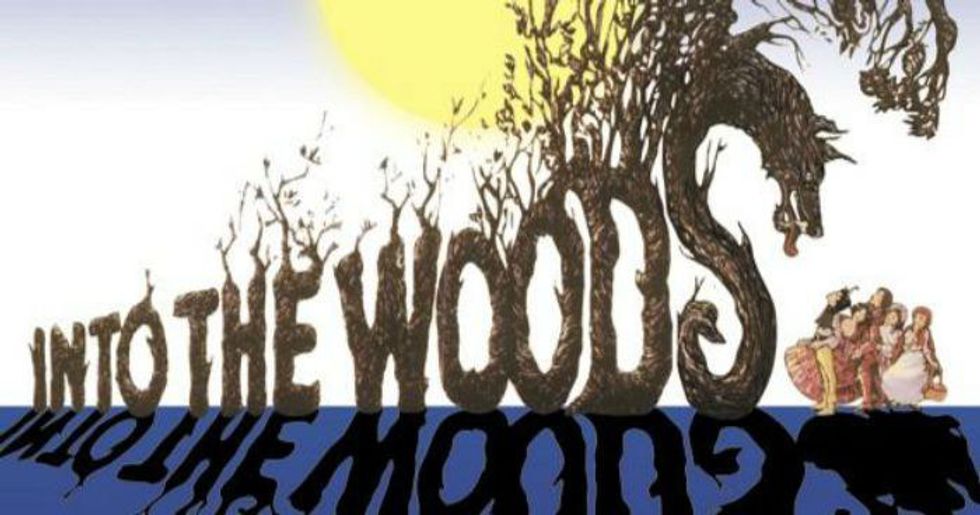

Once upon a time, in every child’s life, the world could be explained easily through fairy tales. Allegorical adventures from a land far, far away feature simple lines between good and evil, punishments for the latter and rewards for the former. The divisions between the two are cut clearly; fairy godmothers and evil queens alike have helped to shape the moral reasoning and worldviews of countless children around the world for centuries. But the world these fairy tales present exists without gray areas. Rarely does this uncompromising polarity exist in the world children grow up to discover. Fairy tales somewhat abandon children as they enter the murkier middle-grounds of adult decisions that confront them every day. The discovery that “witches can be right” and “giants can be good” may be jarring, but moving from the Brothers Grimm to grim reality necessitates the deconstruction of these tales’ ethical simplicity. It is this world-altering realization that Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine explore in their hit Broadway musical, "Into the Woods." The piece picks up where most fairy tales leave off —literally getting to “happily ever after” before the first of the musical’s two acts ends — as a way of bridging the gap between the rigidity of the good vs. evil binary of children’s tales and the combination of these traits that adults discover within themselves and others. "Into the Woods" reinterprets classic fairy tales to move beyond the simplistic ideal of happily every after, and to reconcile the characters of fairy tales with the ambiguous and confusing realities of the human condition.

The ties that bind the fairy tales reconstructed within Sondheim and Lapine’s work are their original characters, who are both the catalyst for many of the major changes within the first act, and for the new conclusions that the authors come to regarding the lessons learned from the post-happily-ever-after versions of the well-known stories. "Into the Woods" weaves the stories of Cinderella, Jack (of beanstalk fame), Little Red Riding hood and Rapunzel through a childless baker and his wife, and The Witch who lives next door to them. Despite desperately wanting a family, the Baker’s “family tree will always be a barren one,” a curse laid upon his father by The Witch following an incident involving the theft of her magic beans. However, The Witch informs the Baker and his wife that this curse will be lifted if they can bring her “the cow as white as milk, the cape as red as blood, the hair as yellow as corn, [and] the slipper as pure as gold,” all key items in the other main fairy tales Sondheim and Lapin examine. This task thus gives the original Sondheim/Lapine characters reason to interact and interfere with the existing events of the other four classic tales, and given this impetus, the Baker and Baker’s Wife, as well as The Witch, lay the groundwork in the first act for the after-happily-ever-after events of the second.

The cow as white of milk comes, of course, from Jack and the Beanstalk. In the tale Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm originally told, Jack flees the beanstalk with money, the golden egg-laying goose, a harp that plays itself and absolutely no consequences. Despite invading the giant’s home, robbing him and murdering him, Jack and his mother are allowed to live in prosperity with no repercussions from this bad deed, as it was committed against a villainous figure, which places Jack in a righteous light. "Into the Woods" happens to climb a slightly different beanstalk. In his haste to acquire the cow, The Baker trades the magic beans his father stole long ago from The Witch to Jack, and Jack excitedly follows the events of his story as usual. But his failure to throw one bean out the window with the rest eventually allows the giant’s wife to come down a second beanstalk in the second act, crushing everything beneath her giant feet and wreaking havoc on the wood. But her reasoning is, by fairy-tale logic, Good; she wants to avenge the wrongdoings committed by “the lad who climbed the beanstalk”. While all the fairy tale heroes in the show view the Giantess as an evil force, Lapine presents the audience with a morally sound argument for her presence, instead shifting the blame for the tragedy and havoc central to the second act more toward Jack. But Jack had his reasons too, and this is one of the key ways Lapine and Sondheim blur the lines between good and evil. Both characters are given a platform for the reason behind their actions, and while the audience knows from experience who the good guys and the bad guys are, they are forced to examine what truly separates the two, and conclude that perhaps, as sung in "No One Is Alone": “You decide what’s right, you decide what’s good”.

The other young protagonist venturing into the world shares her name with the second item The Witch tasks the Baker with retrieving — Little Red Riding hood. Her tale’s central allegory is learning to “never leave the path and run off into the woods by [your]self if mother tells [you] not to”, but Lapine chooses to allow Red’s encounter with her canine foe to change her in a different way. True to the original tale, the wolf is skinned once defeated, but it is Little Red who does the skinning herself, and she dons the wolf’s skin instead of her eponymous cloak, having had her signature crimson accessory nabbed by the Baker in the first act. This action is a cardinal shift in the moral of Little Red’s story; instead of communicating that she narrowly escaped and has learned to listen when “mother said, straight ahead/ not to delay or be misled”, she concludes, by the end of her Act I number "I Know Things Now": "Now I know, don’t be scared/ Granny is right, just be prepared.” Lapine and Sondheim’s libretto empowers Little Red not to fall back into the simplicity of minding one’s parents, but to come to the higher understanding that while she can do what her mother says and avoid danger, it’s alright to stray from the path, so long as she is prepared to deal with what she may find there. This deviation from the childish ending of the Grimm tale embraces a reality that older children and adults often face, the necessity of leaving the bounds set by parents in order to grow as people, and uses the poster girl for minding your mother to explore the idea that you don’t always have to.

A mother is central in the Baker’s quest for the fourth item, the slipper as pure as gold. Motherless Cinderella, silent in her suffering and a faithful visitor to her mother’s grave, is rewarded by her mother’s spirit who, in both the Grimm’s tale and the musical, rewards her with a beautiful outfit in which to attend the king’s festival. There, she loses her shoe on the pitch-coated stairs, and is eventually found by the prince, whom she then marries. The stepsisters, for their wickedness, have their eyes pecked out by birds during the wedding. These details are all consistent between versions. However, in the second act of "Into the Woods," Cinderella’s happily ever after doesn’t seem to be what she thought it would. The main theme of the Grimm’s Cinderella is that the pious and hardworking are rewarded while the vile and unkind are punished. Cinderella is whisked from her modest place at the hearth after her persistent service to those who treat her poorly, and elevated to the highest position possible in the kingdom, all the while getting her true love in the end.

But Cinderella’s prince in "Into the Woods," the iconic Prince Charming, is not all he’s cracked up to be. An idealization of a man who never had reason to develop compassion or authenticity, the prince unapologetically has a brief and steamy rendezvous with another woman in the Act II song "Moments In the Woods." When confronted by his bride, Cinderella’s prince tells her, “I was raised to be charming, not sincere. I didn't ask to be born a king, and I'm not perfect. I am only human.” Their whole conversation regarding the unfulfilling nature of their relationship and the dissatisfaction this brings them is the ultimate debunking of “happily ever after,” and there is an acknowledgement of the unrealistic fairy tale love so many women grow up thinking they will find. Cinderella says it best herself when she says, “My father’s house was a nightmare. Yours was a dream. Now I want something in between.” They part amicably, both conceding that they loved the idea of each other more than the reality of their relationship. Central in Grimm’s telling, Cinderella’s deliverance from a hellish life at home to a life of perfection in the palace is another fairy tale example of a black-and-white world. Having glimpsed both polar opposites, Sondheim and Lapine’s Cinderella decides that she wants the in-between. This realistic actualization shows the maturity the maiden has gained throughout her journey in the woods. She no longer needs the idealized palace fantasy of which she so often dreamed.

This, of course, leaves one remaining object: the hair as yellow as corn. The hair in question is plucked by the Baker’s Wife from none other than Rapunzel, The Witch’s tower-bound adopted daughter. The Witch’s relationship with Rapunzel is overbearing, but her overbearing nature is something that runs deep within all parts of the play. The Witch is a character who sets boundaries and controls them. She sets the parameters for the Baker and his Wife to have a child, and she functions throughout both acts as a voice of reason, most resoundingly in the second.

Act II’s climax has Cinderella, Jack, The Baker, and Little Red playing verbal hot potato as to who is to blame for the giant in their midst. After listening to the nonsense go on for a few minutes, she steps in to bring reason to the situation. Her huge number, “Last Midnight,” beings with a loud “shh-ing” of the other characters in the height of their petty argument, calling them out on their childish short-sightedness. Recognizing that blame and fault are different, she simply says, in no uncertain terms, “If that’s the thing you enjoy/ placing the blame/ if that’s the aim/ give me the blame.” What the other characters think of her in the particular capacity are of little importance to her, as she knows her truth, but the real kicker is when she begins to examine the nature of good and evil.

An obvious choice for the villain, Sondheim and Lapine create with The Witch a very morally complex character who becomes the catalyst for an examination of the ostensibly heroic characters’ actions up to that point in the show. She sings, “You’re so nice — you’re not good, you’re not bad … you’re just nice,” as Sondheim points out that part of the reason these characters are seen as the good guys is that they are nice or merciful, not necessarily that they make the correct or best decisions. Then she continues with, “I’m not good, I’m not nice —I’m just right,” a direct address of the fact that the right thing to do isn’t always the popular choice or something that will paint its perpetrator in a positive light. This differentiation is something that is almost wholly absent in the Grimm’s fairy tales and other stories of the genre, as the understanding the child reader gains in the way the “good guys” and “bad guys” are treated and rewarded/punished is key to their understanding of the moral binary. However, Sondheim and Lapine purposely use The Witch to blur these lines in order to re-examine the way heroes and villains are perceived and classified, even going so far as to suggest that traits of both can exist in one person. The line that seals the deal, however, is The Witch’s next conclusion: “I’m the Witch; You’re the world.” In this show, in this exploration of fairy tales, The Witch isn’t a bad character. She isn’t traditionally heroic, and she certainly passes more criteria for villain than anything else, but the reality is, she floats above it all, reigning the collection of events into the moral themes Sondheim and Lapine are exploring. The Witch sees things for what they are, and because of her refusal to make popular choices or choices that are seen as something a shining hero would do, she becomes their collective enemy. But The Witch refuses to accept that role, and refuses to allow the other characters- the rest of the world- to categorize her so simply. The Witch is the personification of the moral grey area … and she knows it..

The knowledge gained through this Sondheim and Lapine debunking of the ethical dichotomy existent in fairy tales is summed up quite nicely in the Act Two finale, “Children Will Listen,” during which The Witch, eventually joined by the ensemble, reminds the audience of the responsibility they have to the little ones raised on fairy tales in their lives. The lessons told in fairy tales can only serve a child for so long before she begins to turn to the grownups in her world to make sense of the realities of adulthood that the Brothers Grimm forgot to elaborate on. Lapine and Sondheim acknowledge this, but they do so in a way that implores the audience to understand that it is always necessary to be “careful the things you say; children will listen.” The audience leaves reminded that in navigating the ambiguities of their post-fairy tale worldview, “children will look to you/ for which way to turn/ to learn what to be.”

When "Into the Woods" is licensed to theater groups interested in performing it, there are two available versions, as is the case with many Musical Theater International-licensed shows: the full version and “Into the Woods Jr.” Typically, a “Jr” version of a show features a significantly shortened run time, fewer songs and a simpler plot, but "Into the Woods Jr." shortens the show by omitting the entire second act, further supporting the idea that fairy tales are something that get us through childhood questions of morality, but that the full-length Sondheim musical is what addresses how these fairy tale notions can translate into the real adult world. Aimed at elementary school and middle school children, "Into the Woods Jr." really does end with the Act 1 Finale “Ever After.” Everyone lives on in their indefinitely perfect lives, which effectively castrates the musical, leaving it powerless. The second act of "Into the Woods" is the moment for teens and adults who have outgrown the ease of fairy tale-level value judgments and must now face the complexities of life in the gray-areas of the world. By watching the classic rewards, morals and "shining characters on a hill" unravel into much more recognizably flawed and relatable events, audiences are invited to question the certainty of the good vs. evil model they grew up with and out of, and to conclude that the storybook creatures of our youth may have something more complex to teach us.

A fully filmed version of the original Broadway production of "Into the Woods" can be found here.