Humanity has led an odd existence on this earth with every passing generation learning that their place in a grand view was constantly shrinking. For astronomers, this is basically their job description. Time and time again, early astronomers pushed the boundary of what was, at the time, considered impossibilities. However, one astronomer, in particular, was responsible for making the entirety of the human race feel absolutely insignificant. Edwin Powell Hubble not only claims the title for the most punchable name but can also take credit for kickstarting the discovery of the entire universe.

"Yeah it ain't no thing" - Probably not Edwin Hubble

You may recognize the name Hubble from his namesake telescope (which you can read more about in this shameless plug HERE), an observatory that has also revolutionized our outlook on the cosmos. However, to fully understand the advances made by Hubble himself, we must start by looking back on previous discoveries over hundreds of years.

Note: This will be a brief run-through of incredibly detailed topics, not unlike a 4am finals study blitz. If something interests you, feel free to look into it! Better minds than I have written more on the subject.

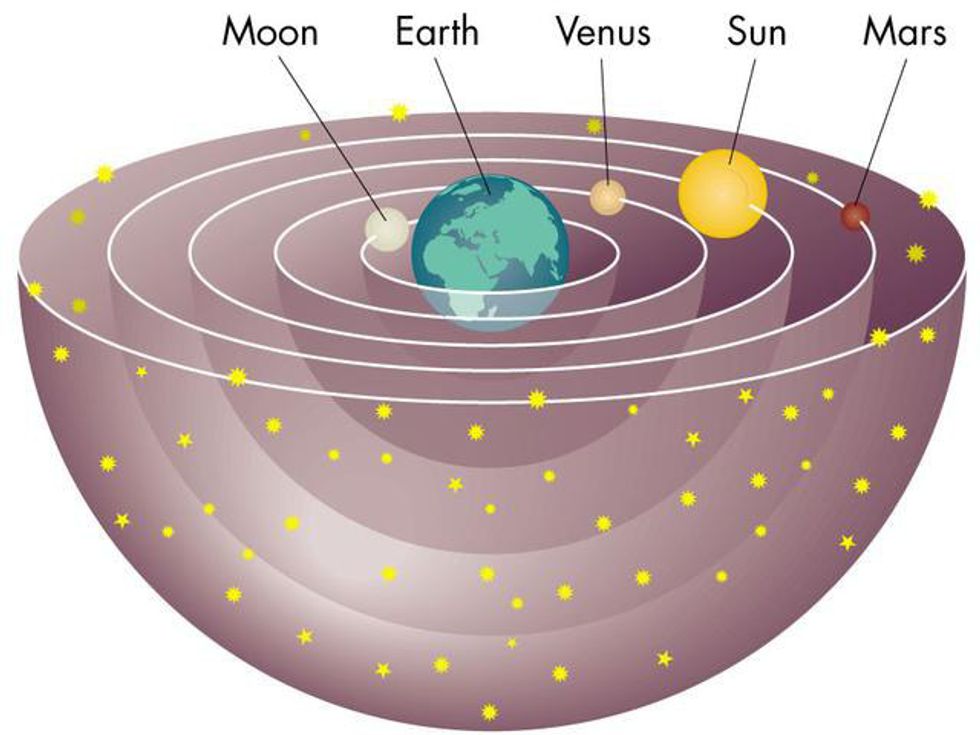

One of the first notions of outer space that was almost universally accepted was the theory of geocentrism or the idea that the earth was the center of the universe, and the sky contained other bodies in orbit around our own planet.

This idea seemed to be common sense, as the ground was always stationary while the sky would consistently move. There were theories over time that argued this wasn't the case. (One of the earliest heliocentric theories was postulated by an ancient Grecian philosopher known as Aristarchus of Samos) These early theories never took off, until the work of the 16th-century astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus. He proposed a heliocentric model in 1514, written into his work "Commentariolus". His ideas were met with immediate controversy, with figures such as Martin Luther decrying his manuscript as heretical, and unbefitting of the church's teaching of a geocentric model. Near the time of his death, there was even a preface added to his book, written by an underling of Luther, who attempted to discredit the work entirely. However, his work was thorough, and another famous astronomer, Johannes Kepler, disproved the notion that the preface was written by Copernicus, paving the way for his theory to take hold.

"Ay yo I got your back bro." - Probably not Johannes Kepler

Consistent discoveries followed this revelation, with our knowledge of the solar system growing with each new planetary discovery adding a new member to our planetary neighborhood. It took thousands of years to form the correct view of our solar system, and we began to discover planets in a tenth of the time. As our knowledge of the solar system grew, we continued to look outward still.

One of the major fields of observation was the study of our own galaxy, the Milky Way. Our knowledge of our own galaxy was not fully appreciated in a watershed moment, but rather the constant reworking of what we believed to be our home in the universe. That word, though, the universe, held a much different idea in the minds of astronomers before the work of Edwin Hubble. The Milky Way, from it's first discovery as a simple band of cloudy light thrown across the night sky, to the realization that the band of clouds were in fact individual points of light, hinting at the sheer number of stars contained within.

"There's gotta be at least 12"

It was generally accepted that the galaxy contained every celestial object that was and ever would be. Stars, planets, asteroids, comets, everything that we could see extended only to the edge of that ghost-like band of stars. Even other nebulae, such as the Andromeda Nebula were part of this amalgamation.

Wait.

If you've never had the fortune of looking at our nearest galactic neighbor, the picture above shows the Andromeda Galaxy, the nearest galaxy to our own Milky Way. Not only is it next door in our stellar neighborhood analogy, it is also the three story mansion to our studio apartment. In more exact terms, the Andromeda Galaxy contains nearly three times the number of stars as the Milky Way, and is nearly 18 times as massive. But with such a staggering size difference, how was it not readily apparent that this formation was on par with the Milky Way, why did it take overwhelming evidence to back up the new claims?

Besides the fact that it looked like this.

The answer comes right back to the curse of all cosmic observation, and the reason that space is called space. The distance between objects in the universe has always been magnitudes more than people first assumed. Our solar system is measured in astronomical units (AU), each one equal to 93 million miles, a distance completely inconceivable on Earth. To put it into perspective, a trip across the Atlantic Ocean was at one time in the past, on of the furthest conceivable distances humans could travel. To travel the length of just one astronomical unit, you must make the trip across the Atlantic 26,874 times.

That's a lot of penny-whistle solos

And that's just the distance from the Sun to the Earth. To reach all the way out to our poor, disrespected Pluto at it's furthest point from the sun, you need to travel almost 50 AU. And even then, that's just distance in the Solar System. Distance between stars is measured in light years, each one of those equal to just under six trillion miles. It's a distance that we cannot experientially comprehend. It's the kind of number that you write out, look at, and wonder if you wrote a few too many zeroes when you were calculating your answer. Just because I like all of you reading this article, I'll give you three guesses at whether or not light-years are enough to measure the distance between galaxies, and the first two don't count. If there's one thing that astronomers find extreme pleasure in, it's creating newer and newer units of distance just so that they don't need to use as much scientific notation when it comes to explaining their work. That's where we get a parsec. Equal to 3.26 light years, a parsec is based on our own revolution around the sun in comparison to an object observed from the earth.

Who knows what the next discovery of our universe will be, maybe we'l' be on the other side of progress, bitterly clinging to the idea that our universe is the only one of it's kind. Only time will tell, but for now we can look to the stars with the knowledge passed on to us from ancient (and not so ancient) observers. We can see further than ever before, as the shoulders of our giants are waiting for the next burst of realization that will bring us ever closer to the truth.