It's a remarkable story of success: an autobiography of a strong-willed woman who runs away from home in Somalia as a young teenager and eventually becomes a supermodel in New York. Woven within the fibers of this powerful novel Desert Flower is a tragic story that so many young girls in Africa, the Middle East, and Indonesia face — the one of female genital mutilation.

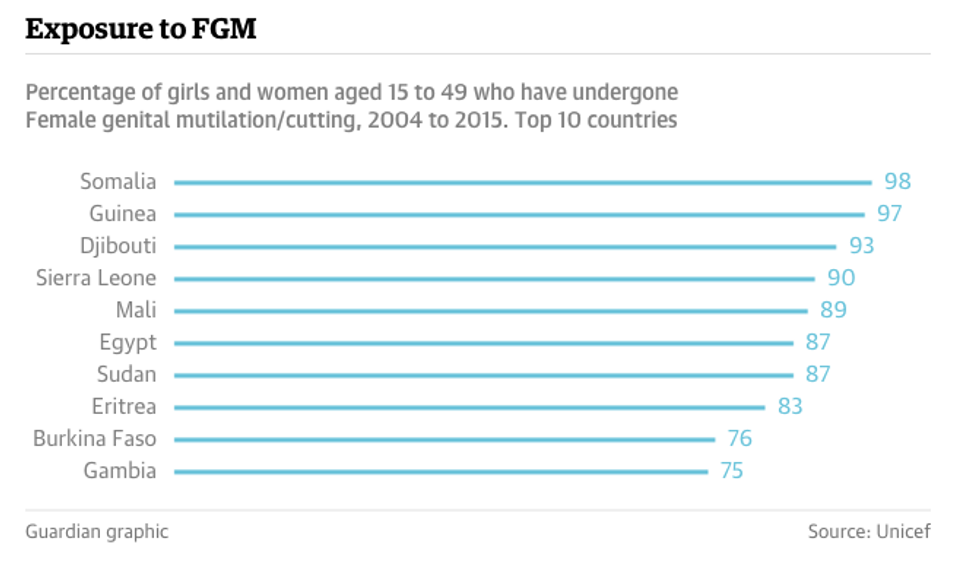

Two years ago, I started researching female genital mutilation as part of my research on women’s reproductive health in the Middle East. Classified into four different types, and as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) comprises all procedures involving partial or total removal of the female external genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons. It’s not something many girls grow up understanding (or fearing) here in the U.S., but it is something that more than 80 percent of girls experience or will experience in many countries in Africa and in the Middle East. Despite the advocacy of anti-FGM/C groups, the UN adopting a resolution to eliminate this practice in 2012, and many religious institutions condemning or banning the practice altogether, the practice is still custom in many parts of Africa and the Middle East. In 30 countries where FGM is concentrated, more than 200 million girls and women alive today have been cut. What strikes as even more tragic is that these coming-of-age celebrations are often celebrated and looked forward to as a procedure that will make a woman more beautiful and suitable for marriage.

I’ve often contemplated what the use is of Americans, specifically, becoming more aware of this practice, considering how "far away" traditions and procedures like FGM/C may seem. First of all, and most importantly, America is actually not immune to this issue or exempt from girls who undergo FGM/C. In fact, a recent study published in February found that the number of women and young girls in America who are at risk of undergoing FGM/C either in the U.S. or abroad has more than doubled, with nearly half a million girls undergoing FGM/C a year. It is not believed to be a practice practiced in America, but rather a tradition valued by immigrants and thus often carried out by taking the girls back to their home country. The second is, of course, that becoming more aware of the plight of others is not only important to our awareness as individuals, women’s rights advocates, and social justice activists, but also helps us connect with the narratives of others that we are otherwise so distanced from.

In Desert Flower, Waris Dirie recounts her struggle with FGM and how her female circumcision adversely affected her physical well-being, her relationships, and her general womanhood. Her periods were excruciatingly painful, her relationships with men hinged on her being circumcised, and she was at risk for severe health complications until she chose to undergo surgery to correct what had been done to her, a necessary medical procedure for which she faced stigma and blame for, to name a few of the hurdles.

Stories serve to make some of the most powerful advocates for change. The more discussion on this practice, both here and abroad, the more conversation can be facilitated on how to best eliminate this practice, often a deeply rooted cultural tradition. Waris Dirie’s extraordinary story sheds light on an important issue worth addressing in every way — there should be no girl in this world undergoing such an often crudely performed procedure for no medical benefit, let alone be looking forward to for her acceptance as a woman. Just two weeks ago, undoubtedly influenced by Waris Dirie’s efforts, the Somali prime minister signed a petition to ban FGM/C in his country, marking the first public effort to ban the practice in a country where almost every girl is cut. The country needs to additionally exhibit a willingness to enforce the law and a commitment to educating the public about the need for change in a culturally sensitive way, but with these efforts, Somalia could very well soon be a champion of the movement for zero tolerance on FGM/C.

The U.S. has banned the procedure and taking women outside the U.S. to be cut, and in 2012, Obama issued an Executive Order for the implementation of the U.S. Strategy to Prevent and Respond to Gender-Based Violence Globally to combat this practice, but our efforts will never be enough until this practice is completely eliminated. Change happens (and has clearly already happened) when governments, societies, and individuals work together. Waris is just one of many women who prove that, though the consequences of this practice can be eventually overcome, it is of utmost importance that we first dedicate ourselves to eliminating it in order to fully empower women and girls. No female should be taught to believe or grow up believing that the horrors of FGM/C are a part of what it means to be a woman.