Despite an explosion in technology and a huge increase in worker productivity, the middle class continues its 40-year decline. Millions of Americans are working longer hours for lower wages, and median family income is almost $5,000 less than it was in the year 1999, adjusting for inflation. The wealthiest Americans in the country, the top 1 percent, own 48 percent of the nation's wealth. There’s a great deal of discussion over the demise of the middle class in America. A common phrase is that the rich get richer, the poor get poorer, and the middle class gets smaller. What influences this reduction?

First, one must define what the "middle class" truly means. Thefreedictionary.com defines the middle class as “the socioeconomic class between the working class and the upper class, usually including professionals, highly skilled laborers, and lower and middle management.” Economic experts have a loose definition of the middle class; some define the middle class by income brackets, others define it by lifestyle, and some say it’s a state of mind. Whether one is considered middle class or not most commonly depends on one's income. One of the most specific definitions limits it to the middle fifth of the nation’s income ladder. A broader definition includes everyone but the poorest 20 percent and the wealthiest 20 percent. An additional way economic experts use to determine if one is defined as middle class is wealth; some Americans may not be making middle-class incomes, but have a lot of savings and/or investments.

Having a better of understanding of who exactly the middle class is, one can dive deeper into the demise of the middle class. The wealthiest Americans in the country, the top 1 percent, own 48 percent of the nation's wealth. Simon Pathe, from PBS, reports that just because the 1 percent owns 48 percent, that doesn’t mean the other 52 percent belongs to 99 percent of the population.

Each of the 50 states has seen its share of middle-class families shrink from 2000 to 2013, thanks to stagnant incomes and rising housing costs, according to an analysis from the Pew Charitable Trusts. The eroding middle class poses a serious threat to the nation's economic growth, given that American households with mid-range incomes fuel spending on everything from cars to housing. Yet, during the past 15 years, more of those middle-income families have slipped out of the "sweet spot" of the American economy. This is due to a confluence of negative trends such as declining or stagnant wages and a growing income gap.

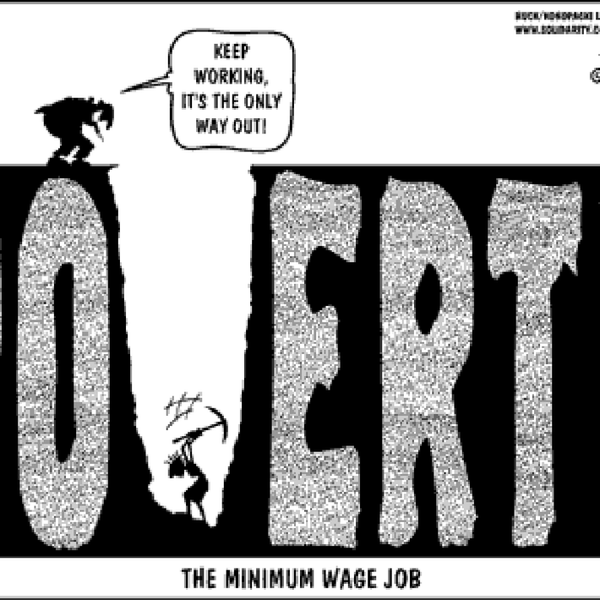

Mike Patton of Forbes.com argues that as more become rich, the poor benefit as the private sector thrives and opportunities emerge. They argue that there is equal opportunity for anyone who desires to succeed, and America has bred a culture of laziness. Stating “there is a growing discontentment emanating from those who believe their answer is found in governmental decrees rather than from one’s own initiative and hard work.” While the author makes several valid points, one can make the argument that worker laziness is actually on the decline. According to epi.org, worker productivity is on a steep slope upwards, increasing 254 percent since 1948 while real hourly compensation over this period has increased only 113 percent. It looks like workers are increasingly productive despite the wages they earn.

Donald J. Boudreaux and Mark J. Perry of The Wall Street Journal make the argument that Americans are able to enjoy a longer period of life. Stating that Americans are able to spend on modern life’s “basics”—food at home, automobiles, clothing and footwear, household furnishings and equipment, and housing and utilities. Boudreaux writes “Bill Gates in his private jet flies with more personal space than does Joe Six-Pack when making a similar trip on a commercial jetliner. But unlike his 1970s counterpart, Joe routinely travels the same great distances in roughly the same time as do the world's wealthiest tycoons.” The quantities and qualities of what ordinary Americans consume are closer to that of rich Americans than they were in decades past. Consider the electronic products that every middle-class teenager can now afford—iPhones, iPads, iPods and laptop computers. They aren't much inferior to the electronic gadgets now used by the top 1 percent of American income earners, and often they are exactly the same. The rate of these has fallen from 53 percent of disposable income in 1950 to 44 percent in 1970 to 32 percent today.

It used to be that when the U.S. economy grew, workers up and down the economic ladder saw their incomes increase, too. But over the past 25 years, the economy has grown 83 percent, after adjusting for inflation—and the typical family’s income hasn’t budged. In that time, corporate profits doubled as a share of the economy. Workers today produce nearly twice as many goods and services per hour on the job as they did in 1989, but as a group, they get less of the nation’s economic pie. Millions of Americans are working longer hours for lower wages, and median family income is almost $5,000 less than it was in the year 1999, adjusting for inflation.