In the spring of 1886, John S. Pemberton brewed the first Coca-Cola. As a pharmacist, a soda was not his original intention. Coca-Cola started as a syrup for another one of his medicinal drinks. He distributed the syrup to several local soda fountains where customers could purchase a chilled glass of the syrup combined with carbonated water and ice for a nickel. However, the company did not experience immediate success. With his health failing, Pemberton decided to sell his company before his death in August of 1888 to Asa G. Candler, another pharmacist in Atlanta (Boney 92).

Candler partnered with an old friend of Pemberton’s, Frank M. Robinson. Robinson is the one the company’s initial success is attributed to. He not only pushed advertising, but he also changed the formula for the syrup, removing the trace of cocaine in Pemberton’s original recipe by the enactment of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906. As the success of the company continued, global expansion began in 1898 with Canada and Cuba adding chains of the company (Boney 92).

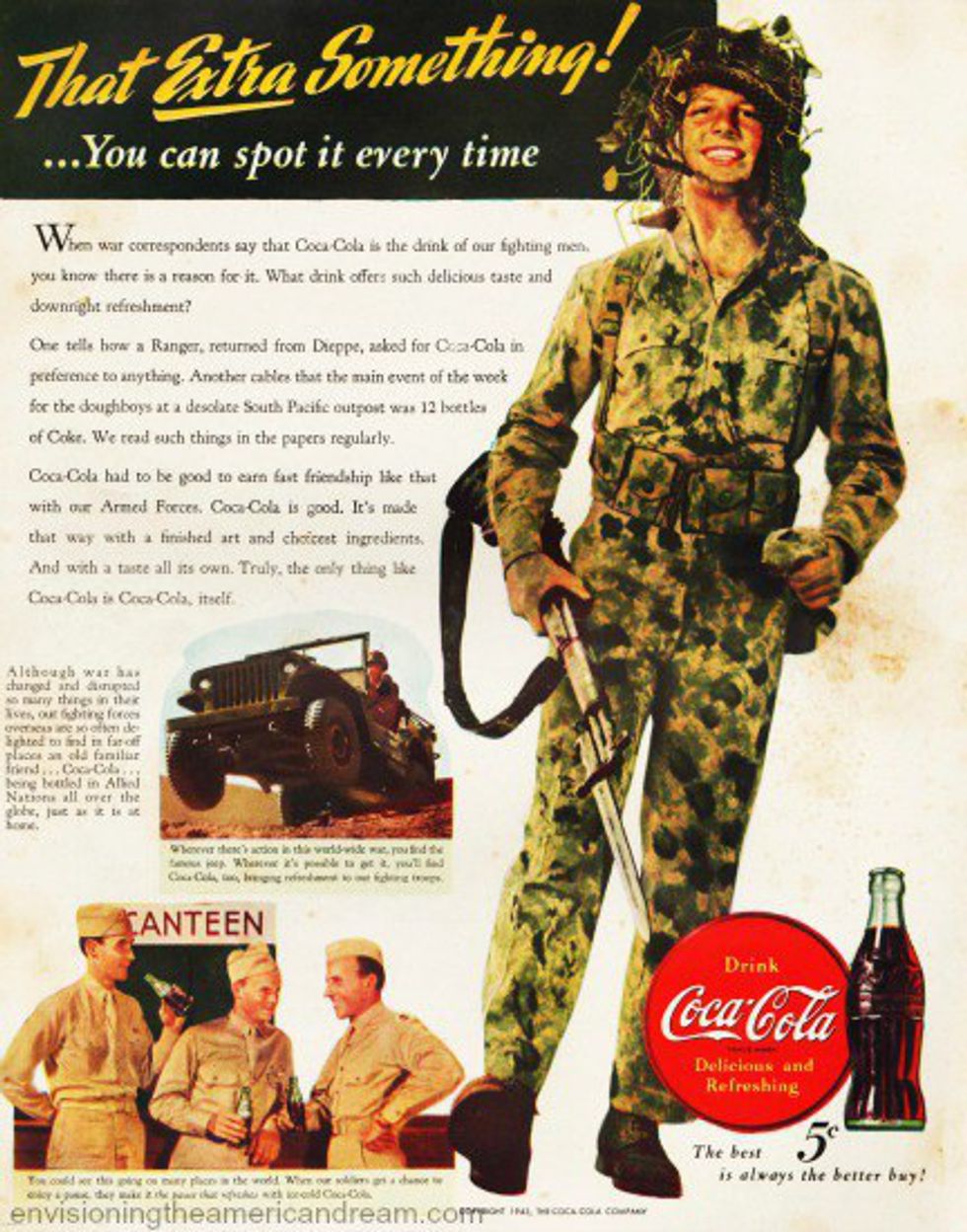

Although they had plants in other countries, the Coca-Cola company did not have a strong consumer population until the second world war, which allowed them to commence their journey as a successful, global company. Robert Woodruff, who took on the job as the president of the company in 1923, saw the war as a way to expand the company. Woodruff believed, “that every man in uniform should have access to a bottle of Coca-Cola for five cents” (McBride 80).

Coca-Cola not only quenched their thirst, but also held its place as a taste of home, allowing the company to take a patriotic approach to advertising. While Americans see the globalization of Coca-Cola as a positive process, many outsiders disagree. Instead of representing all nations, the patriotism of the company makes it a company of the United States resulting in the term, “Coca-colonization,” which, like “McDonaldization” and “Americanization,” stands for cultural imperialism (McBride 81-82). Initially, cultural imperialism may seem harmless. What is wrong with sharing a part of our culture with other nations? In short, the harm comes from taking away from the pre-existing culture in those nations and forcing the American culture on them.

Julia Roberts, a student at University of Ottawa, created a blog as one of her assignments. In her post, “Coca Cola: The Ultimate Reflection of Cultural Imperialism,” Roberts states that during a lecture she learned “‘Coca Cola’ is the second most known word in the ENTIRE WORLD” (Roberts). The wide spread familiarity with the company is a direct result of its globalization through cultural imperialism. In some areas, the cultural imperialism of Coca-Cola helps developing countries. For example, substituting Coca-Cola for water in recipes reduces the risk of bacterial infection in areas with limited access to clean water.

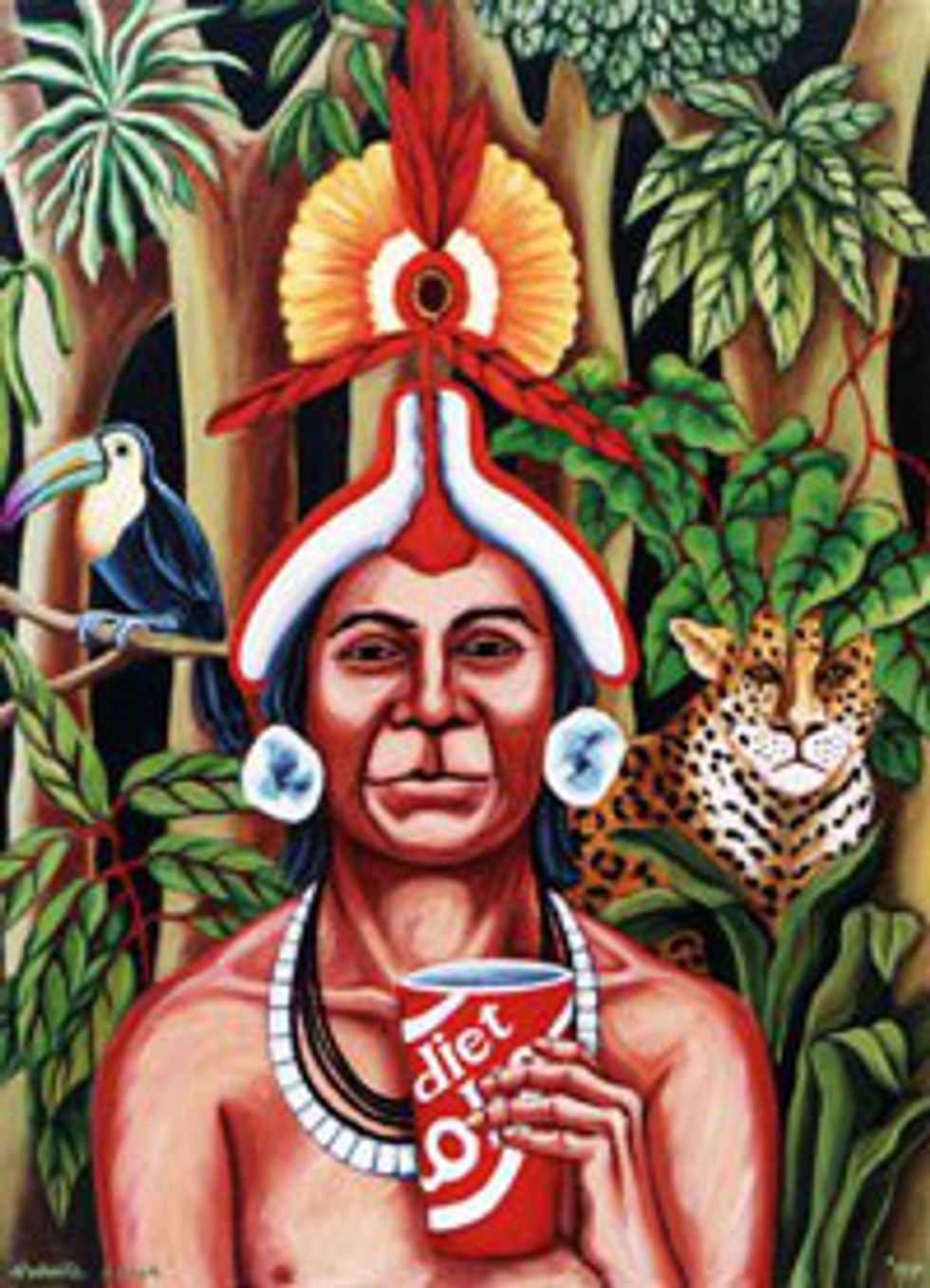

However, despite its usefulness, locals continue to protest Coca-Cola’s focus on marketing in poorer regions (McBride 83). In his article, “Cultural Imperialism in Columbia,” Peter Woodman states that a shaman told him that the only ones interested in adopting the American lifestyle are the youth. Furthermore, the shaman stated, “the community used to be happy, and function well when it was still based on indigenous ethics” (McBride 84). If these regions function well on their own terms, why does America feel the need to force its culture on them? Woodman claims the reasoning behind cultural imperialism is the culture shock: “the south American indigenous culture strikes a hard contrast to western culture. Therefore in the eyes of the US, it must be destroyed and devalued… being indigenous is now generally looked on as old fashioned and inferior” (McBride 84). As a developed nation that thrives off of the need for everyone to have the latest gadgets, the United States does not understand neither the importance nor the meaning of having a traditional culture.

Cultural imperialism detracts from the values and traditions already instilled in nations. Imperialized nations view the Coca-Cola company as, “a foreign invader that is violating the national space” (Varman 692). Wanting to keep their nation’s ideology, the anti-consumption movement against Coca-Cola products developed, with the most notable movement taking place in India. Anti-Coke activists believe the cultural imperialism threatens their identity as a nation by sucking youth into the American lifestyle at a young age.

The youth of India are deviating from the traditional culture to an Americanized one; They wear and drink the same as the youth in America. If this continues, the Indian culture will soon be a thing of the past. Is this really what society wants? One of the greatest beauties of this world is being able to experience diversity. Unless cultural imperialism comes to a stop, the world will lose its diversity.

In addition to detracting from cultural diversity, the anti-consumption movement focuses on working conditions and health concerns: “the ‘real working conditions’ inside the Coca-Cola plant involve violations of India’s minimum wage law and exploitation of workers” (Varman 694). Similar to the thousands of trafficked workers around the world, workers on the Coca-Cola plant receive low wages. Additionally, Coca-Cola’s employees receive little to no benefits. Unions are often dismissed. However, one union success included winning a $2 wage for an 8-hour work day. This, however, is still far below a livable wage. Furthermore, hazardous work zones create health concerns for employees. Harsh chemicals used to clean the bottles seep into their shoes, resulting in blisters covering their feet.

Although Coca-Cola may “make good things taste better,” society cannot sit back, “enjoy life,” and “have a coke and a smile” (“A History of Coca-Cola Advertising Slogans”). With the villagers and farmers unable to help themselves, those in developed countries must stand up for them. Too often, when small, local companies expand to the global scale they become unethical. Therefore, instead of supporting the company by purchasing their products, consumers should protest the company whether that means not buying items from Coca-Cola or gathering a group to protest outside, raising awareness to those uneducated about the issue.

Boney, F. N. "First Atlanta and Then the World: A Century of Coca-Cola."

Getz, Christy, and Aimee Shreck. "What Organic and Fair Trade Labels Do Not Tell Us: Towards a Place-based Understanding of Certification."

"A History of Coca-Cola Advertising Slogans." .

Mcbride, Anne E. "Have Your Coke and Eat It Too: What Cooking with Coca-Cola Says about Cultural Imperialism."

Roberts, Julia. "Coca Cola: The Ultimate Reflection of Cultural Imperialism."

"Unethical Companies:Coca-Cola."

Varman, Rohit, and Russell W. Belk. "Nationalism and Ideology in an Anticonsumption Movement."