My first interaction with the cultural construct of race came about in half-day kindergarten. The teacher asked us, a class of fifteen predominately white five year olds, why we celebrated Martin Luther King Jr. Day. It was January and we had just finished reading a picture book about Ruby Bridges. We had grown up in a calm, small suburb of Seattle, and were stunned to learn that adults could be so awful to a little girl just wanting to go to school.

A well-meaning blond boy raised his hand to answer the question. When called upon, he said, “So that way we can celebrate being able to go to school with all sorts of kids like Adri, Chase, and Rita.”

Adri, Chase, and Rita (yours truly) were the few darker-skinned kindergarteners in the class. Adri and Ben were African-American.

“And Jonathan,” a little girl with honey-colored curls added. Jonathan was Asian.

That day, because I had been grouped together with Adri and Ben in our short, simple discussion, I went up to my father before dinner and asked, “Daddy, are we black?”

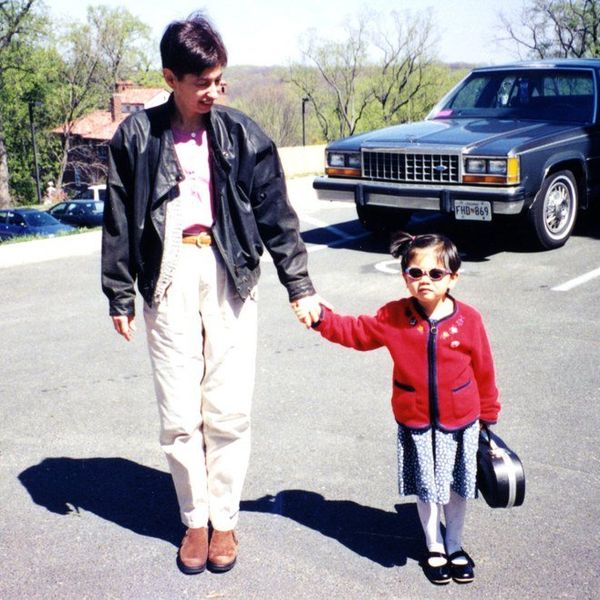

My dad, a white man who spent his childhood being shuttled back and forth between Great Falls, Montana and Indio, California (where Coachella is now held), was utterly flabbergasted. His eyes, their lopsidedness and shape being one of the few physical traits that I’ve inherited from him, widened. He slapped down the Sportsmen magazine he’d been reading onto the table and gasped, “No! Where did you get that idea from?”

“We were talking about Martin Luther King Jr. Day.”

My parents and I were in the kitchen. My mother stood a few feet away stirring a pot of pasta, and after hearing my question had stopped and set the spoon down. My dad looked perplexed. She looked horrified. My mom is from Indonesia. If you don’t know what that means, she’s Asian. If you don’t know where that it is, it’s an archipelago above Australia. My coloring can be attributed to her.

That day, my father took it upon himself to sit me down and I learned that I was two races: White and Asian. Only until recently did official documents and surveys aside from the Census begin allowing you to mark multiple boxes when they asked for your race. Before, me and millions of other Americans had been checking “Other”, and sometimes had to scrawl in something when prompted in parenthesis to (specify). In retrospect, I guess it was good that I learned “what” I was in kindergarten, since standardized tests began in third grade and that’s when you had to start marking those facts down.

When I was around thirteen, I began finding more people like me. Broadly speaking, people who acknowledged that they were more than one race and were willing to deal with a few more questions, a couple more boxes to check, and general confusion. There was a certain camaraderie in sharing stories of how grocery clerks would always assume you were with one parent or the other but never both, how you were constantly asked “What are you?” and how it typically ended in a guessing game, how you dealt with the “Oh, you don’t look like you’re [insert one of the races you claim to be], the odd semi-compliment of “Halfies are so attractive”, or the funny looks you’d get when someone read your name and saw your face. We call ourselves mixed, unique, mutts, halfies, or outsiders.

In middle school, I came across Kip Fulbeck. While I had been fortunate to meet plenty of kids like me with a White parent and an Asian parent, I had never seen all of us “mutts” compiled together into an exhaustive project. Not only were there relatively straightforward representations of half-Asian, half-White people, but there were those who were Hispanic, Middle Eastern, Aboriginal, or African in a stunning array of combinations. Fulbeck is the creator of “The Hapa Project,” which is an online community as well as published photography book. It has brought widespread recognition to multiracialism, particularly to those of partial Asian-descent. Seeing all those pictures, of people who had never fit neatly into a single category, was invigorating.

Before 1967, my parents’ union would have been illegal. It wasn’t until Loving v. Virginia that laws prohibiting interracial marriage were invalidated. Thirty-three years later in 2000, the US Census allowed for people to select more than one box when reporting their race. Yet problems still persist with the current system. For instance, a demographic that has recently come into focus are Arab-Americans, who are forced to put down that they are “White/Caucasian”. Many, especially Trump supporters, would be quick to contend. There have been proposals to expand ethnic categories within the “race/ethnicity” section, as “Hispanic” is the only ethnic category currently available on most forms (and even then, it is inaccurately non-exhaustive). Perhaps one of the most pressing issues is that the cultural construct itself means little (what is race? That’s a discussion beyond the length of my article and the breadth of my platform), it groups people who have vastly different ethnic origins based off flaky geography, and is, as expected, based off racist ideology. A nicely condensed lesson featuring Franchesca Ramsey on the history of race, and the convoluted “science” behind it, can be seen here (watch it, it’s less than five minutes and very informative).

I don’t anticipate the questions, backhanded compliments, or general comments to end anytime soon. But I do anticipate greater recognition of multiracial people and minorities in public discourse and the media, and perhaps there will be less pressure to pick “one or the other.” I am not a check in a box. Rather, I am a proud anomaly with growing numbers that is shaking the system.