For the last week, every time I’ve sat down to write this article, all I could do is stare at the screen. All of the tragedies that have wreaked far too many American lives this week, and I cannot even fathom just what words I can use to say what needs saying.

Now I’m sitting here an hour before deadline, and I can feel that hot, wet burn behind my eyes as I try to keep from crying. I still cannot find the words to detail how much my heart hurts, to show how heavy the world feels, at the knowledge of all the recent deaths that fill my Facebook news feed, that pop up in the corner of my screen as CNN notifications, that has elicited conversation from family and friends and heated tension to a boiling point.

Philando Castile. Alton Sterling. Brent Thompson. Patrick Zamarripa. Michael Krol. Lorne Ahrens. Michael Smith.

These are the names that made the news this week. Seven names, seven families in grieving, seven lives lost.

---

I grew up in the South, in boiling humidity and mostly white communities. My friends were all white, and my parent’s friends were generally all white. A majority of the families who lived in the neighborhoods we lived in were all white. Racism wasn’t something that had ever really occurred to me, or wasn’t something I’d ever had to give much thought, because it wasn’t something I’d ever been exposed to. At least, not in that sickeningly disturbing way I’d come to recognize as I grew older; there were of course the “black jokes” and the way we whispered words best not repeated as children, because we’d learned from our parents, from our grandparents, from our very communities.

We were taught in school about the Civil Rights movement, about plantations and slavery and history, about the Civil War and what it was really fought for. But none of it really meant anything because it wasn’t something we’d ever had to deal with. At least, not in my small friend group. Besides, we were also taught that racism didn’t exist anymore.

In fact, it wasn’t until I moved to southern Florida with my family that I really even began to understand what it meant to be racist because suddenly all of my friends were black or Hispanic, instead of white. When I was interested in a boy, I was told by friends and family alike that I shouldn’t date "someone like that," someone who wasn’t white. It wasn’t "respectable" for a young woman like me. When I worked late at night, I crossed the street if I was going to walk near a group of men or boys on my way home.

In a free study period, the teacher would occasionally jump start conversations. Admittedly, I tuned most of them out and focused on reading or homework, but there was one conversation that I still remember almost ten years later because we got to talking about stereotypes. By this point, I knew better than to say anything about the stereotypes I’d grown up with (most of them were slowly falling away in my mind anyway,) but out of nowhere I was lambasted by a young, black male in the class.

He said to me, “You’re white. You probably have a lot of money and live in a nice house. You’ll get to go to college and stuff. You don’t really have anything to complain about.”

At the time, I was so angry! What did this kid know, to make assumptions like that about my life? He didn’t know anything about me, and yet here he was acting as if he knew my whole life story. He didn’t know that my family was anything but rich, and that the house that we lived in my parents could hardly afford. He didn’t know that college was a far off dream for me, and I was as likely to have student loans as he was. I was so angry, but I couldn’t bring myself to say anything out of nerves; I was the only white student in the class, and the only girl.

Looking back, I can say definitively that we were never raised to be racist; both of my parents are open and inclusive, friends with anyone they get along with no matter their race, gender, or sexuality (politics and religion are other matters entirely!). But, the culture of the south often perpetuated an underlying inclination towards racism, however subtle.

---

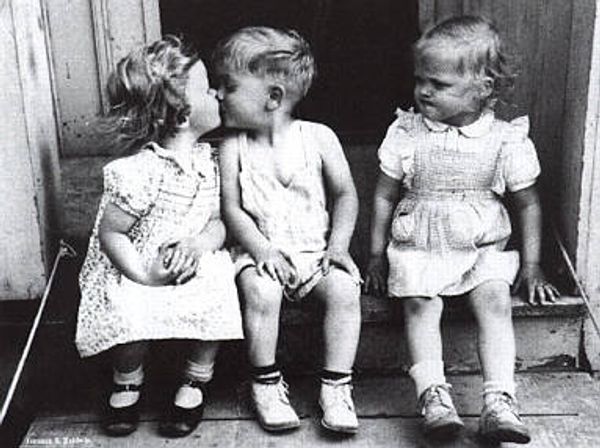

When I was in elementary school, we lived in duplexes on a quiet road consisting mostly of families with children around my age. I remember my best friend at the time was Iesha Brown, a little black girl that lived up the street. She was an only child, and the only girl in my grade on the street that I liked playing with. I often spent time at her house after school and we would watch Sailor Moon, or go outside and play across the street with my brothers and their friends on the big tire swing, or climb trees until our limbs almost quaked with fear that made it difficult to shimmy back down.

There was a cop that came around in the afternoons occasionally, stopping his cruiser in the center of the street. I remember thinking, as little girls are wont to, that he was handsome and fun to play with. He gave out little teddy bears to the girls, the fur softer than a dandelion, and those hard plastic badges to the boys.

The children, white, black, and Hispanic, would gather around his car eagerly and he’d ask about us, and speak to parents who might have gathered too.

He made us smile. He made us feel safe, though as children I don’t think we really understood that feeling, and he never differentiated between the colors of our skin. To him, we were just children and our parents were just the parent’s of the children who lived on his route.

---

I’ve heard it said that you can’t fix something until you’re willing to admit that it’s broken in the first place.

Some Americans are unwilling to admit that anything needs fixing. Some Americans are unwilling to see the injustice of an unarmed person being shot down by a crooked cop. Some Americans are unwilling to see that not all cops are crooked.

Since January 1, 2016, there have been 601 police shootings across the U.S. With the sniper attack in Dallas, the number of police officers killed by firearms in the U.S has gone up to 26 this year, a 44% increase from this time last year.

There are people who will say after reading this that I support the Black Lives Matter movement and that must mean I hate cops. There are also people who say that I support the men and women who try to protect us, and that must mean I hate black people.

I will never, ever understand how favoring one means I must automatically despise the the other. To say that I hate one because I love the other would be to say that I support terrorism, because I don’t believe all Muslims are terrorists. I don’t support terrorism, and I definitely don’t think that all Muslims are terrorists. I will defend fiercely any cop who was doing his or her job justly, just as I will fervently support the black lives matter movement, and any other movement like it that works to annihilate the systemic oppression of people.

The seven lives lost this week will never be returned. The families of the fallen will live the rest of their lives, hurt, angry, confused. And these deaths, though they should be a moment that forces us all to take a good, long look at our government and polices, at ourselves and our cultures, will be used to tout hatred and anger for one group or another.

In his address to the American people in 1968, Robert Kennedy made these remarks in his eulogy for Martin Luther King:

“….In this difficult day, in this difficult time for the United States, it's perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in……What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence and lawlessness, but is love, and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or whether they be black.

You can read the full speech here.

These are the two parts of the speech Kennedy gave that I think resonate most with the current state of American division.

At a time when we should be coming together, we’re fighting each other, casting blame and creating more chaos. I do not personally know any of the seven people who died this week. But I mourn for them, my heart aches for them, because they died needlessly, violently, out of hatred, out of anger, and out of ignorance.

In the end, more people will die. Cops will shoot another unarmed suspect, and in turn more cops will be killed out of distrust and anger. There is more distrust in our nation now than I think there has ever been, and we’re all scrambling about like fire ants, filled with venom to infect the first person who scares us.

Americans are still unwilling to admit that racism exists. Americans are still unwilling to admit that there are some cops, not all, who kill indiscriminately. Until we can admit to these two harrowing issues, nothing will change.