When I was very young, I took an aptitude test that placed me at a “gifted” or “advanced” level of learning. This isn’t uncommon—approximately 6-10 percent of students, or 3-5 million, are considered gifted, according to the National Association for Gifted Children. For me, like many, this meant that I sailed through regular lessons and was often bored in class, which led me to develop an overactive imagination and smart mouth. However, I was privileged enough to attend private schools that my parents paid for, and for the most part, I was given the resources to grow and develop as a gifted student.

Here I am, little and lucky, although I didn't know it yet.

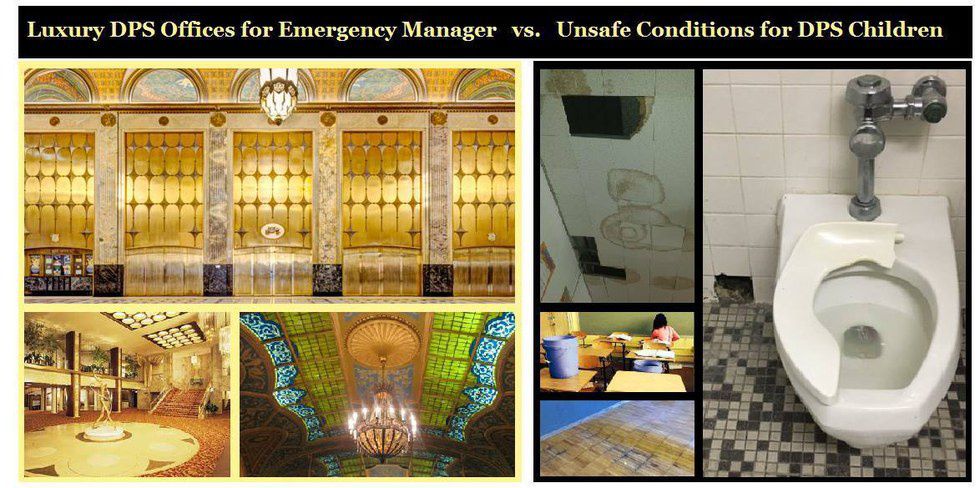

There is an enormous chasm between students like me (who were given resources and encouraged) and students in many in-crisis public education systems. You may have heard or read about the appalling conditions facing Detroit educators and students: toxic black mold, completely inedible meals, horribly out-of-date textbooks. Not a single student deserves this, yet 48,000 Detroit schoolchildren are being forced to endure not just sub-par, but downright dangerous and woefully inadequate learning conditions. It’s clear that something needs to be done.

Public schools in the United States originated with colonial one-room schoolhouses, intended to socialize children and teach them basic literacy and arithmetic. These later became free “common schools” for reading, writing, and arithmetic, and few students pursued education past the eighth grade. Those who did were almost always wealthy upper-class students whose families could afford to send them to college. After the common schools, where most students ended, “factory model schools” became popular. These trained students to be laborers in factories or agriculture. This is the model that is more or less used today, with a few modifications accounting for technological advances.

The problem with this system in the modern day is that it doesn’t equip students to become critical thinkers and problem solvers. It equips students to be “docile subjects and factory workers” according to a documentary by Greg Whiteley. Think about it: both factories and schools signal changing classes, or shifts, with a bell. All break times are assigned. Workers and students are given repetitive tasks (“busy work”) that are little more than a way to keep them occupied. It teaches information, but not understanding. In this day and age, a computer can find and organize information far more effectively than even the most intelligent human being. But students are still being taught to regurgitate information that they may or may not understand. This is the problem at the core of our education system.

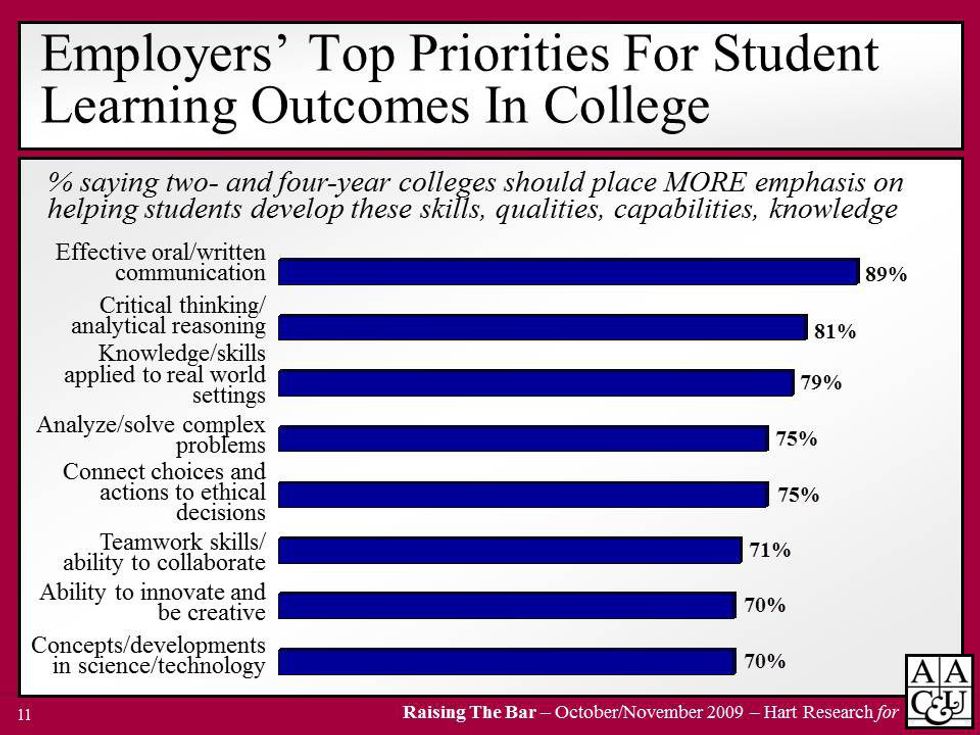

Here's a quick rundown of what employers actually want schools to teach students.

There are different approaches to fixing the education system. One popular opinion is that the school day should be restructured—no more bells, no more 40-minute class periods per subject. One way to do this is using the block scheduling system, which many schools have already adopted. This means students have no more than 4 classes per day for longer periods of time, giving them opportunities for longer discussions and cooperative activities—much like what will be required in the workplace.

Some say that restructuring the school day is not enough to teach interpretive skills, but the entire school year must be restructured as well. This may mean year-round school with short breaks built into it. In fact, prolonged summer breaks may actually lead to loss of knowledge, known as the “summer slide”. Another theory is to encourage more all-day education for younger children (3-4 years old), which has been shown to increase high school graduation rates.

Others believe the problem lies not in the K-12 grade schools, but in higher education: in its cost and accessibility. Students like me, who have been provided resources to achieve grades and are at least middle-class, will have few problems attending and graduating from college. But what about students who are poorly equipped, like many Detroit students? One solution for them may be to reduce the cost of higher education, or make pathways to higher education other than a four-year degree (like trade school, community college, employer training, apprenticeships, or certificates) more publicized and funded. Even four-year degrees should be priced as what they are: necessities to earn a living wage rather than luxuries for the upper class.

So while it has been demonstrated that some students do succeed in this education system, most are set up to fail because of a lack of resources and a lack of instruction. If our generation is to thrive, the education system must change to reflect what 21st century employers want from graduates rather than what 18th century employers wanted.