There is one way to make something last forever. Maybe remaking exact replicas every 20 years? Wait … is that the same?

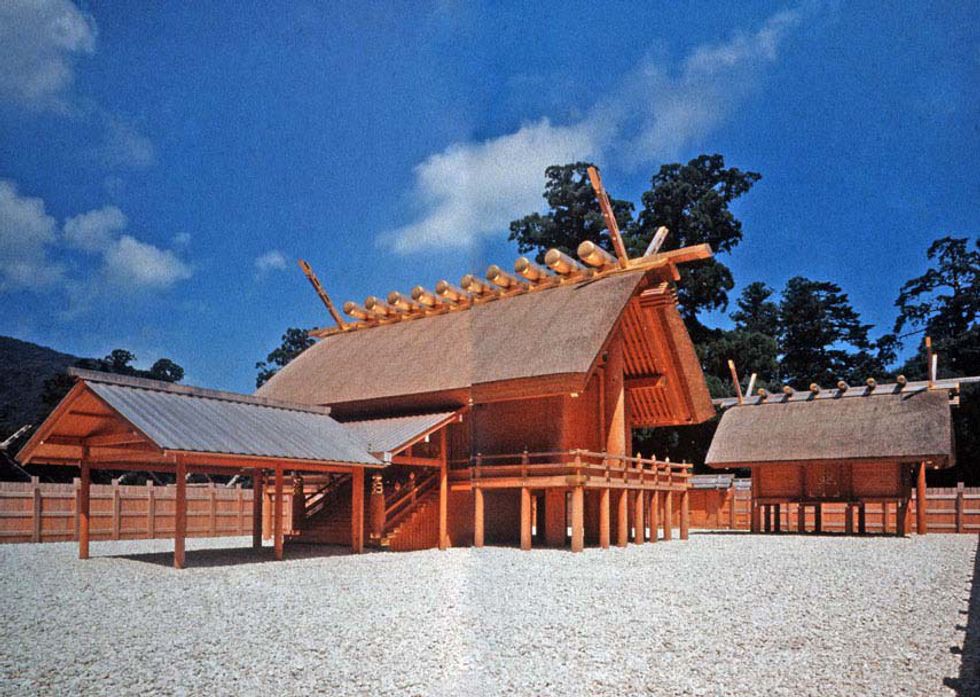

The Shinto have discovered the fountain of architectural youth. The Shinto shrine, located in the city of Ise, in the Mie Prefecture of Japan, is more than 1300 years old. The rustic, thatched huts that enclose the spirits of earth deities, called "kami," appear as authentic and intact as the day they were first formed. This is because they are literally dissembled, recycled and rebuilt with fresh cedar wood every 20 years.

This is a fascinating concept, considering that the primary function of these buildings is spiritual and not practical. There are no building codes to keep up with, in fact, no one is even allowed to enter the inner shrine, except the monks that live in, and maintain Ise.

The ceremony dedicated to the reconstruction of the shrines is called Shikinen Sengu. There are several motivations behind this practice. Due to the ancient joinery and lack of weatherproofing, the shrines would deteriorate and be lost without refurbishment. The Shinto choose not to change their building practices or materials for the sake of tradition. The reconstructions also provide a crucial opportunity for the ritual knowledge to be passed from one generation to the next.

The ideal of eternal youth is honored through this process of renewal. And as a way to uphold this ideal, Ise is kept in impeccable, and identical condition to its prototype. There are two main sanctuaries that sit in adjacent plots. Both are rebuilt during Shikinen Sengu. Once the new shrines are built, the most higly regarded kami, sun goddess, Amaterasu is ritually transferred to whichever of the main shrines she was not in before. She is given a fresh dwelling place as an offering of rejuvenation.

The last reconstruction occurred recently in 2013, and if all goes to plan, the subsequent rebuilding will fall in the year 2033.

The shrines are not the only things that undergo reconstruction at Ise. Sacred offerings, from pilgrims over the centuries are also remade.

Buddhism was introduced to Japan sometime during the sixth century. A common association with Buddhist belief, is the idea of accepting impermanence. While Shintoism predates Buddhism in Japan, the two grew compatibly together.

Other people imagine the sacred as attached to particular objects. In my experience of sacred objects, like my late grandmother’s hand mirror, the idea of a replica is not meaningful. I like the mirror, but its true value lies in the fact of its originality.

Both ways of thinking preserve originality, just in different ways. The Shinto preserve originality by maintaining a physical idea through time, represented by replicas. The objects themselves are not as important as the ideas they represent.

Others maintain originality of a beloved object by leaving them unaltered. The result of this is eventual decay, but the knowledge of authenticity is timeless. Both ways seem to have a relationship with the material and immaterial worlds, and both seem to value originality.