Rap is tough to talk about critically. People generally talk about music from a subjective standpoint, and that's valuable. There's something special about injecting pure passion into art which gives it life beyond the artist's creation. Artists generally want people to feel an emotional connection to the things they make, so there is an inherent subjectivity to conversations on art. However, it is not enough to let yourself see music (or any art really) only as you like it. Taking time to uncover the magic of music makes the consideration of each project an experience beyond just listening. One of my favorite people, Neil DeGrasse Tyson, has some line somewhere about how understanding the wonder of the universe doesn't take away from its awe-inspiring power. Rather, understanding more about the universe shows us exactly why we should be so enraptured with its function. The same goes for rap (or, again, any art).

Digging into how certain projects achieved certain ends is just as important as the ends themselves. (Note: "Projects" includes tracks, albums, mixtapes, music videos, etc.) For example, if you think Kendrick Lamar's "To Pimp A Butterfly" (2015) was awesome, that's awesome. If you think it sucks, that sucks. Either way, if you leave that album at an impression, you're missing out. Homeboy spent three years since the release of his wildly acclaimed good kid, m.A.A.d city (2012) in a studio with George Clinton putting together this gargantuan. The roots of each track are bound to lines of a poem delivered to the West Coast GAWD, grounding frenetic lyricism in a winding wave. (Note: that sentence takes the place of a 3,500-word essay, there's only so much you can say without saying it all.) Themes of racism, classism, depression, self-esteem, and family all pull in different directions, but never pull the project apart. The album is far too daunting to try to analyze it track-by-track for a passing read, so I won't. The purpose of this brief Kendrick-centric discussion is just to impress the idea of hip hop projects as dense cultural texts to be studied just as much as they are liked or disliked (See: "Enter The Wu-Tang" (36 Chambers) (1993); "Let's Get It: Thug Motivation 101" (2005); "Soul Food" (1995).)

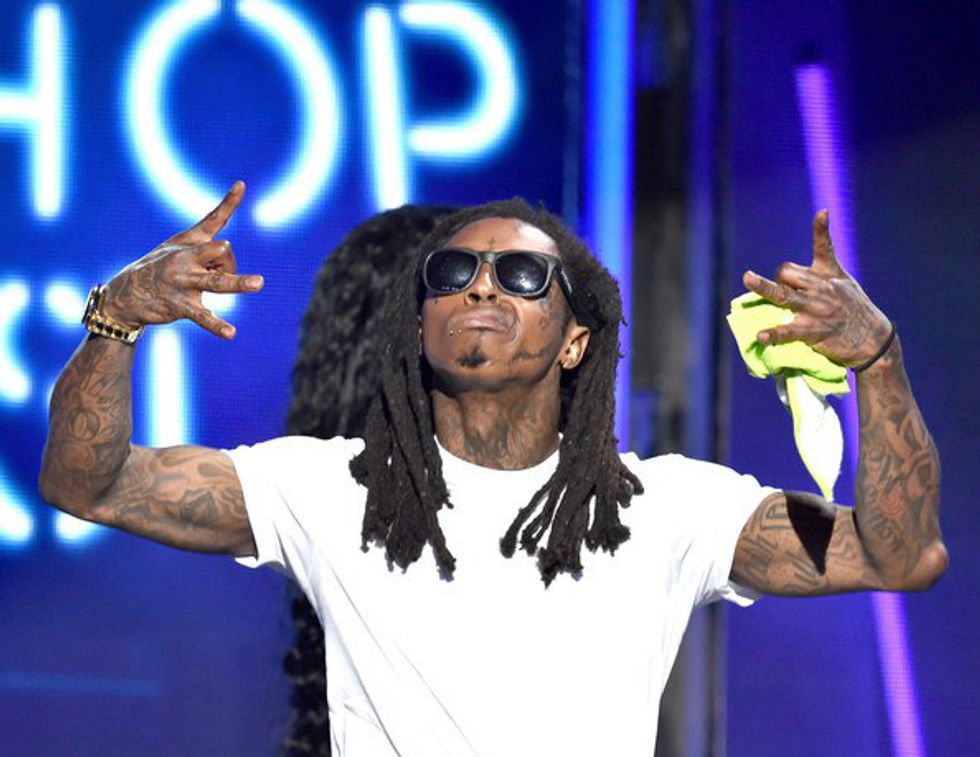

If studying the cultural texts is important, then so is studying the patterns that comprise those texts. (Note: "Text" is a more academic cousin of the previously mentioned "project.") One of the easiest studies in hip hop is Lil Wayne (aka Lil Tunechi AKA Weezy F. Baby), and with his "No Ceilings 2" mixtape dropping a few weeks ago, I have a good enough excuse to talk about him. For one thing, Wayne is and always has been very easy to listen to. He brings everything to you, and he is the best rapper who ever put flow before being witty, and put being witty before having a depth of content. Wayne can be serious, and he can do it well (See: "Hustler Muzik"; "Misunderstood"; "Tie My Hands"), but he has not made a legendary career of social commentary or deep insights into the human condition. His legacy is lined with hilarious one-liners and cursory phrases that make you think about lasagna for a long time. With Weezy, you feel everything before you understand anything. A few characteristics that distinguish the goodness of rap from the goodness of other musical or poetic endeavors rest comfortably in the topsoil of Tunechi's roster of albums and mixtapes.

Flow

Regardless of what he says, Wayne always makes sure that the rhythm of his rhyme-telling cements his statements as prophetic declarations. Every line sounds like either a set-up or a punchline, partly because most are actually set-ups or punchlines, but mostly because he runs certain lines together (the set-up) then stretches out and swings emphasis into other lines (the punchline). In his 2011 single, "Abortion," one of his set-up/punchline combos is "I'm shooting for the stars, astronauts dodge bullets." The first part of the line, "I'm shooting for the stars," runs together with syllables of equal time and emphasis. The latter half of the line carries the same number of syllables, but emphasis is placed on certain syllables (bold and italicized) to give the punchline momentum. Wayne has this way of getting high off of himself that creates a likable gravity—a gravity directly influenced by his flow.

Wit

Lil Wayne will most notably be remembered for delivering witty lines one after the other. His tracks are not built to tell stories, they're built for Weezy to spit out codeine-induced statements about random things as he sees them. A personal favorite of mine is from his track, "Blunt Blowin'." It goes, "Young Money's eatin', the label's gettin' fatter, / And yeah the tables turned, but I'm still sittin' at 'em." Wayne is the Godfather of taking everyday phrases, like "turning the tables," and flipping them on their heads to fit his slender bravado. Another dimension of the line's wit also lies in what follows, "I'm a bad motherf----r 'cause the good die young." Because there's no separation between this statement and its predecessor, there exists an implied notion that being a bad man is among the reasons he can't be shaken from the table of the rap game.

Imagery

Another thing Lil Wayne does that every good rapper includes is the injection of vivid images tied to action to illustrate a message. There's only so many ways to complain about people who leech off of you, and not everybody likes to talk about those people in public. Lil Wayne, however, is not everybody and he very aggressively gets out ahead of the issue. "Man, when that cookie crumble, everybody want a crumb. / Shoot that hummingbird down, hummingbird don't hum." I don't think Weezy understands the context of the phrase "that's the way the cookie crumbles," but that kind of helps him in this case. (Note: Here is what happens when Kanye West fundamentally misunderstands a cultural phenomenon.) Wayne still makes it work, because a cookie is a food and also a form of sustenance so it fits with the idea of people feeding off of him. Also, very astutely, he notes that if you shoot a hummingbird it will no longer hum, which is probably the least offensive way to threaten someone's life, but also the most hostile context in which any human has ever referenced a hummingbird.

In all sincerity, listening to Lil Wayne gives you some insight into how arbitrary our system of language can be. In a genre that exclusively championed crime, misogyny, and a duo that included Project Pat during Weezy's prime, that insight is a noble one. As with most of rap, you take the good with the bad listening to Wayne. Sometimes he uses words and phrases effectively. Sometimes he lazily says Rick Ross is fat. Maybe the best analogy for Mr. Carter's music is a game of Russian roulette, except every chamber is full of similes, allusions, alliterations, and countless other rhetorical devices that blow your mind in the simplest ways. It would seem that after years of playing this game, the chamber has gotten jammed so now he just throws the whole gun at whatever beat he's on (See: Everything after 2012). Even if he never makes another "Carter II" (2005), "Drought 3" (2007), or "Dedication 4" (2012), Weezy remains the Whitman of new millenium rap music.