Like most 20-year-olds on winter holidays vacation, I’ve been devoting a great deal of time to binge-watching. Most recently, I’ve fallen in love with two extremely different reality-cooking shows: "Cutthroat Kitchen" and the "Great British Baking Show."

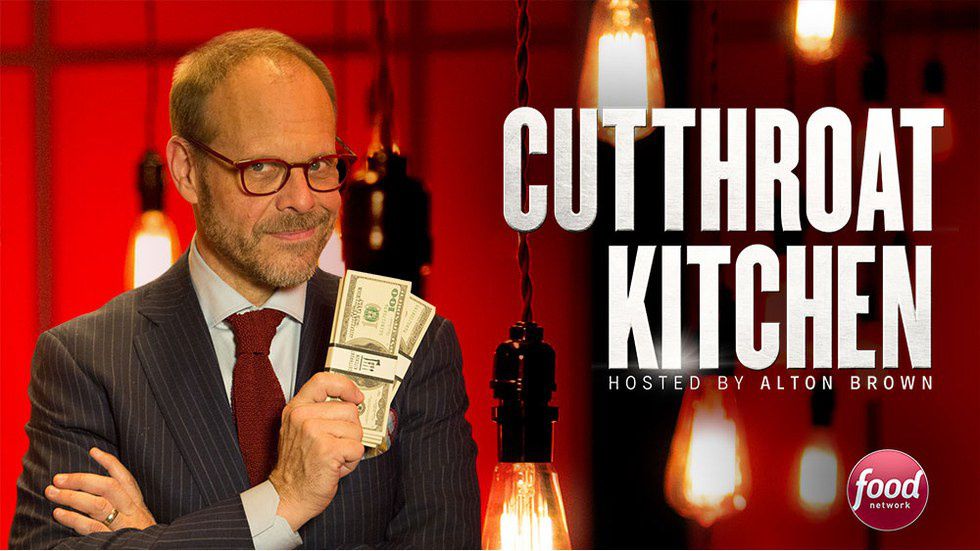

The former was introduced to me by one of my best friends in one of our long lazy days before we had to retreat to our families’ houses for Christmas. "Cutthroat Kitchen" has a unique model that shapes its competition: four chefs compete against each other; they are assigned a dish to prepare in 30 minutes; and, they are given $25,000 to spend on auction items. These auction items are designed to sabotage competitors, and they can be anything from taking away a chef’s utensils (so they make utensils out of aluminum foil) to making them used cheese whiz in a chicken cordon bleu. As you can imagine, "Cutthroat Kitchen" gets pretty, well, cutthroat. It is remarkable how these ambitious (and narcissistic) people will go to extremes to make a stranger—a colleague, really—suffer. After over half an hour of sabotage, an impartial judge who is blissfully ignorant of the subterfuge tastes the chef’s creations. The only aspect the judge cares about is what is on the plate. There is not much room for empathy in "Cutthroat Kitchen," not from the host, competitors, judges, or even the viewers.

"The Great British Baking Show" is much different. In this particular competition, 12 amateur bakers from all over the UK spend their weekends baking in a tent that is pitched on the lawn of a great British estate. The bakers create all variations of cake, pastry, bread, and biscuts to be judged by the renowned bakers Mary Berry and Paul Hollywood (yes, those are their real names). When I first watched it, I called it “The Anti-Cutthroat Kitchen,” because almost every aspect of the show is wildly different. The hosts still make several food puns, but their main job on the show is to help the bakers relax and relieve tension, the judges are hard to please, but they are constructive and sympathetic, and even the competitors themselves are amiable and helpful to one another. At the end of each weekend’s set of challenges, one contender is given a sheriff’s badge and the title of “Star Baker,” and another is, most regrettably, eliminated from the competition. Even though a baker is sent home, it is done in a most sympathetic way; every single episode ends in a massive group hug.

After binge-watching all the episodes I could find of these two very different shows on Netflix, I developed a theory: Cooking shows are allegories of real life. One can find elements of both competitions everywhere. Often, we see more "Cutthroat Kitchen" than anything else, because it is dramatic and exciting. People constantly trying to one up each other and creating enemies out of colleagues has become a cultural staple. Often in jobs or school—especially in creative and artistic fields—not much thought is given to how or why, only on what people can create. In this brand new year, though, I am trying to see more Great British Baking Show, where everyone can afford to be more kind than cruel, more constructive than detrimental. I am lucky to study music at a school where even though the competition is fierce and close, colleagues are still supportive and kind. And on days when nothing seems to go right and our bread dough doesn’t rise enough, we are still able to smile, which as the great Mary Berry says, “That’s what it’s all about.”